Stanley Kubrick, among the many other skills that made him perhaps the best-known auteur of the second half of the twentieth century, could craft an immediately memorable scene. Moreover, he could construct entire films out of nothing but immediately memorable scenes. This goes especially for his Cold War black comedy Dr. Strangelove: Or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, whose fans tend to quote to each other not individual lines but entire five‑, ten‑, fifteen-minute stretches from the movie. One such oft-reenacted scene, the phone conversation in which President Merkin Muffley warns inebriated Premier Dimitri Kisov of the U.S. bombers headed toward Russia appears at the top of the post, in the original black-and-white, with the original voices of Peter Sellers, Peter Bull, and George C. Scott, and — with nothing in front of the camera but Lego bricks and Lego men.

Just above, you can see Sellers’ performance as the titular eccentric, alien hand-syndrome-suffering doctor physically rendered in Lego. Dr. Strangelove fans know the scene comes late in the film, when a long series of errors and acts of unreason on all sides has made imminent the moment of mutually assured destruction. “I had to take out the famous scene of Slim Pickens riding the bomb and the nuclear holocaust credits to have this video viewable, because those scenes were taken directly from the movie,” explains these videos’ creator, a Youtube user by the name of XXxOPRIMExXX. “I was hoping to have the Slim Pickens scene done in Lego by now but I just never had enough time or effort to do it, maybe some time in the future.” Let me say that, if I have confidence in anyone to get that job done, I have confidence in someone with the stamina to successfully build a Lego War Room.

Related Content:

Inside Dr. Strangelove: Documentary Reveals How a Cold War Story Became a Kubrick Classic

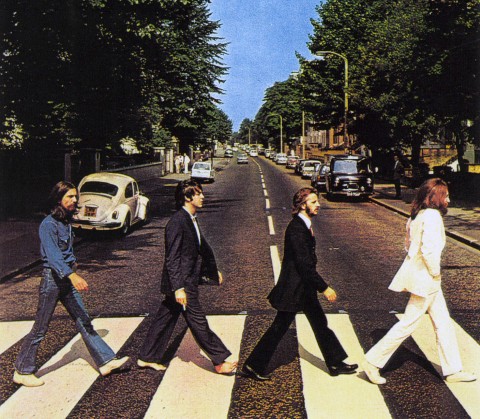

Classic Photographs Remade Lego Style

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.