Soon after I started driving, back in high school, I got a mobile phone capable of SMS messaging. As with any technology not yet widespread, it then seemed more novelty than convenience; I hardly knew anybody else with a cellphone, much less with one capable of receiving my messages. But in the intervening dozen years, everyone started texting, and the practice turned from oddity into near-necessity, no matter the time, no matter the place.

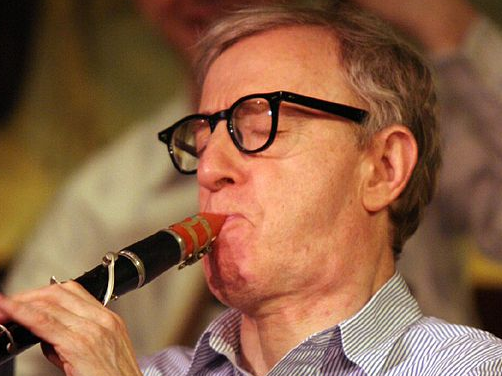

Now, having taken for granted the ability to instantly send short messages across the city, country, or world to one another, society has, inevitably, begun to focus on the associated dangers of texting. But few of us have thought quite as hard about them as has Werner Herzog, director of Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Fitzcarraldo, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, and now a documentary against texting while driving. But don’t people already know the dangers? Haven’t public service announcements cautioned them not to do it, and stiff, fee-threatening laws gone on the books across America?

Judging by the sudden popularity of Herzog’s new 35-minute film From One Second to the Next, sponsored by cell service provider AT&T, a German New Wave luminary’s words carry more weight. “I’m not a participant of texting and driving — or texting at all,” many have already quoted him as saying, “but I see there’s something going on in civilization which is coming with great vehemence at us.” Despite not having driven regularly since high school, I do on my rare occasions at the wheel feel that strangely strong temptation to text in motion. Having watched Herzog’s unblinking take on the real-life consequences of doing so — unpayably high medical bills at best, paralysis and death at worst — I don’t see myself giving in next time. Whether or not it similarly effects the students of the 40,000 schools in which it will screen, it marks a vast improvement upon all the murky, heavy-handed cautionary videos I remember from my own driver’s ed days. Perhaps what Herzog did for Bad Lieutenant, he should now do for that classroom classic Red Asphalt.

You can find From One Second to the Next in our collection of 550 Free Movies Online.

Related Content:

Portrait Werner Herzog: The Director’s Autobiographical Short Film from 1986

An Evening with Werner Herzog

Errol Morris and Werner Herzog in Conversation

Werner Herzog Has a Beef With Chickens

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.