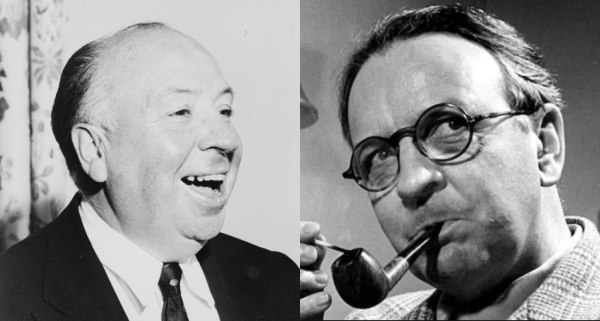

Images via Wikimedia Commons

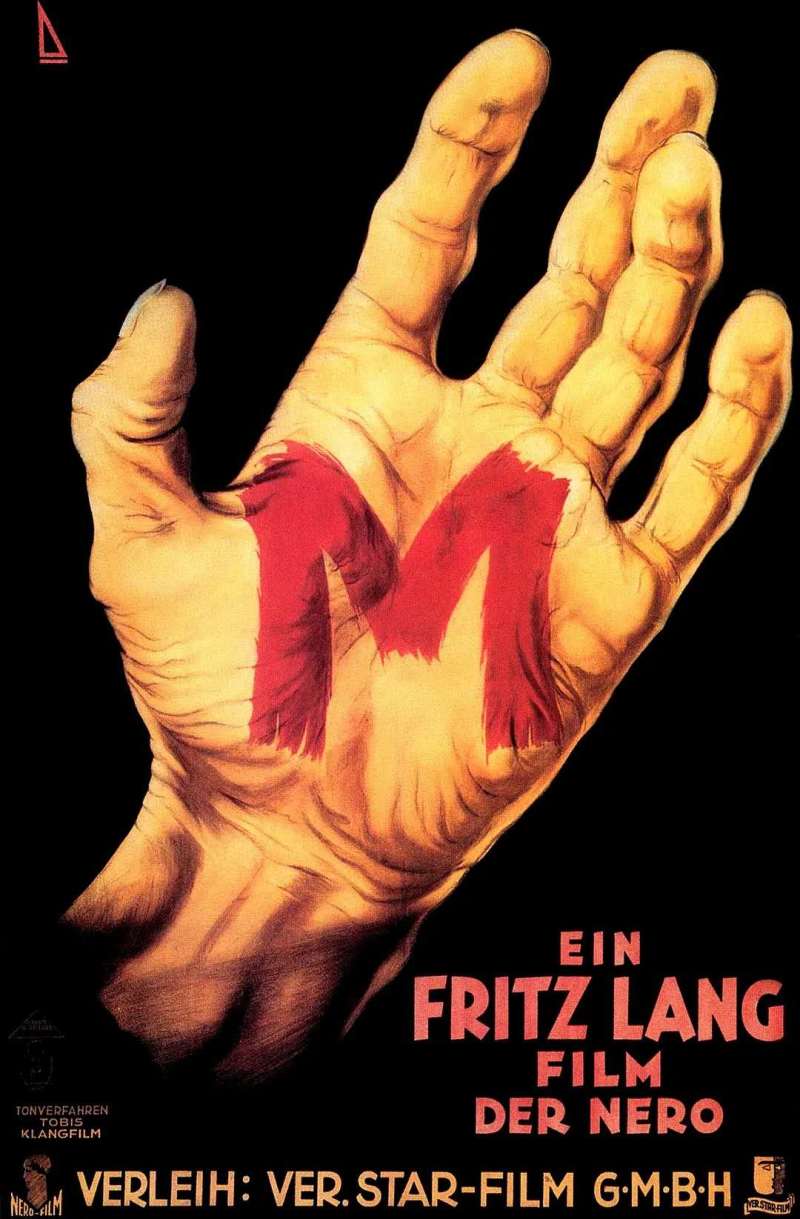

Alfred Hitchcock, like several other of the twentieth century’s best-known auteurs, made some of his most widely seen work by turning books into movies. Or rather, he hired other writers to turn these books into screenplays, which he then turned into movies — which, the way these things go, often bore little ultimate resemblance to their source material. In the case of his 1951 picture Strangers on a Train, based upon The Talented Mr. Ripley author Patricia Highsmith’s first novel of the same name, Hitchcock burned through a few such hired hands. First he engaged Whitfield Cook, whose treatment bolstered the novel’s homoerotic subtext. Then he importuned a series of the brightest living lights of American literature — Thornton Wilder, John Steinbeck, Dashiell Hammett — to have a go at the full screenplay, none of whom could bring themselves sign on to the job. Then along came the only respected “name” writer who could rise — or, given that many at first thought Highsmith’s novel tawdry, sink — to the job: Philip Marlowe’s creator, Raymond Chandler.

The Big Sleep author wrote and submitted a first draft of Strangers on a Train. Then a second. He would hear no feedback from the director except the message informing him of his firing. Hitchcock pursued “Shakespeare of Hollywood” Ben Hecht to come up with the next draft, but Hecht offered his young assistant Czenzi Ormonde instead. Together with Hitchcock’s wife and associate producer, Ormonde completely rewrote the script in less than three weeks. When Chandler later got hold of the film’s final script, he sent Hitchcock his assessment, as featured on Letters of Note:

December 6th, 1950

Dear Hitch,

In spite of your wide and generous disregard of my communications on the subject of the script of Strangers on a Train and your failure to make any comment on it, and in spite of not having heard a word from you since I began the writing of the actual screenplay—for all of which I might say I bear no malice, since this sort of procedure seems to be part of the standard Hollywood depravity—in spite of this and in spite of this extremely cumbersome sentence, I feel that I should, just for the record, pass you a few comments on what is termed the final script. I could understand your finding fault with my script in this or that way, thinking that such and such a scene was too long or such and such a mechanism was too awkward. I could understand you changing your mind about the things you specifically wanted, because some of such changes might have been imposed on you from without. What I cannot understand is your permitting a script which after all had some life and vitality to be reduced to such a flabby mass of clichés, a group of faceless characters, and the kind of dialogue every screen writer is taught not to write—the kind that says everything twice and leaves nothing to be implied by the actor or the camera. Of course you must have had your reasons but, to use a phrase once coined by Max Beerbohm, it would take a “far less brilliant mind than mine” to guess what they were.

Regardless of whether or not my name appears on the screen among the credits, I’m not afraid that anybody will think I wrote this stuff. They’ll know damn well I didn’t. I shouldn’t have minded in the least if you had produced a better script—believe me. I shouldn’t. But if you wanted something written in skim milk, why on earth did you bother to come to me in the first place? What a waste of money! What a waste of time! It’s no answer to say that I was well paid. Nobody can be adequately paid for wasting his time.

(Signed, ‘Raymond Chandler’)

Note that Chandler, ever the writer, points out his own “extremely cumbersome sentence” even as he summons so much vitriol for what he considers a lifeless script. As a longtime resident of Los Angeles by this point, and one who had already worked on the screenplays for The Blue Dahlia and Double Indemnity, he knew well the procedures of “the standard Hollywood depravity.” But nothing, to his mind, could excuse such “clichés,” “faceless characters,” and dialogue that “says everything twice and leaves nothing to be implied.” We could all, no matter what sort of work we do, learn from Chandler’s unwavering attention to his craft, and we’d do especially well to bear in mind his preemptive objection to the argument that, hey, at least he got a big check: “Nobody can be adequately paid for wasting his time.”

Whatever your own opinion on Hitchcock, don’t forget our collection of 20 Free Hitchcock Movies Online, nor, of course, our big collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

Raymond Chandler: There’s No Art of the Screenplay in Hollywood

Watch Raymond Chandler’s Long-Unnoticed Cameo in Double Indemnity

Alfred Hitchcock: The Secret Sauce for Creating Suspense

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.