If you are a movie maven, you know about the Criterion Collection. Since the days of Laserdiscs, Criterion has made a name for itself by amassing a vast and thorough catalog of indie films, art house flicks and the occasional blockbuster. They distribute DVDs of directors as diverse as Akira Kurosawa, Jane Campion, and Stan Brakhage.

For their website, Criterion has asked a number of filmmakers, writers and other cultural figures to come up with their Top 10 Criterion movies ever. They are fascinating, illuminating and often surprising.

The late, great band Sonic Youth – which made a name for itself for its loud, growling guitars and endless layers of noisy feedback — picked some remarkably quiet, meditative movies: Yasujiro Ozu’s contemplative late masterpiece Floating Weeds tops the list and Chantal Akerman’s three-hour long minimalist masterpiece Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles comes in at number two.

Likewise, low-budget horror legend Roger Corman picked Michelangelo Antonioni’s high art masterpiece L’avventura as his top pick. “Never has ‘waiting around’ been so glorious,” he writes.

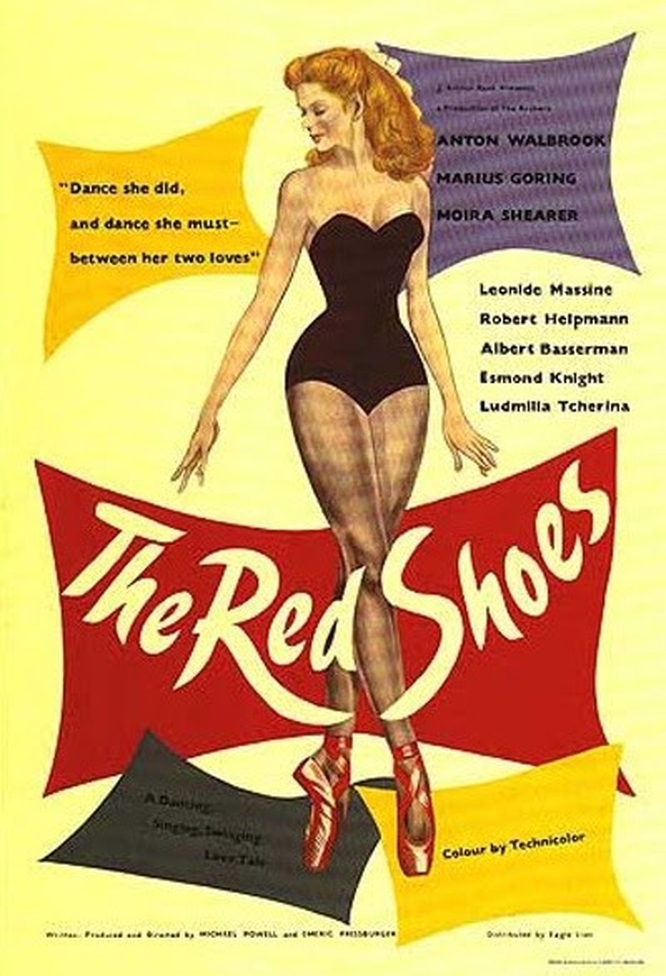

Less surprising are Martin Scorsese’s picks. He puts Roberto Rossellini’s Paisan at number one and Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s Technicolor marvel The Red Shoes at number two. Scorsese has on multiple occasions declared his love of the former and was central to getting the latter restored.

Edgar Wright – director of Scott Pilgrim vs. the World and last summer’s apocalyptic comedy The World’s End – proudly picked Brian DePalma’s Blow Out as his top movie. “I have heard people call themselves Brian De Palma apologists,” he writes. “I am proud to say that I am a huge fan without any caveats.”

And The Exorcist director William Friedkin reveals himself to be a fan of Alain Resnais, placing both Night and Fog and The Last Year at Marienbad high on his list. His praise of the recently departed French New Wave icon’s most famous movie is also an eloquent defense of any challenging movie.

I’ve seen Marienbad at least twenty times over the past fifty years, and I don’t understand one scene of it, but what a fantastic experience. I don’t understand the Grand Canyon or Schoenberg’s Transfigured Night, either, but they continue to move me.

You can see all of the Criterion top ten lists here. Other figures on the list include Jonathan Lethem, the Beastie Boys’ Adam Yauch, James Franco, Lena Dunham, Guillermo del Toro, Wes Anderson, John Lurie, Brie Larson, Donald Fagen & More.

Related Content:

The 10 Greatest Films of All Time According to 846 Film Critics

Martin Scorsese Reveals His 12 Favorite Movies (and Writes a New Essay on Film Preservation)

Stanley Kubrick’s List of Top 10 Films (The First and Only List He Ever Created)

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow.