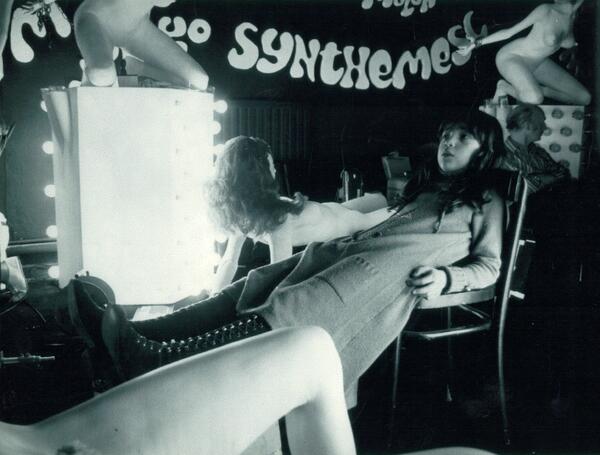

A film that began its life as a script called Who Killed Bambi?, written by Roger Ebert and Russ Meyer, The Great Rock and Roll Swindle (trailer below) became a farcical caper starring the Sex Pistols minus their lead singer. Johnny Rotten had quit the band at this point and appears only in archival footage. Mostly The Great Rock and Roll Swindle was a vehicle for Malcolm McLaren to sell himself as the guru of punk and the driving force behind the band. Directed by Julien Temple (who also made the far superior Sex Pistols doc, The Filth and the Fury), Swindle is also notable for almost launching a Sid Vicious solo career, and it might have worked, were it not for his epically destructive flame-out in 1978.

The film saw release two years later, and produced a soundtrack album, which I remember finding in a used record bin—pre-Google—and thinking I’d discovered some long lost Sex Pistols album. One listen disabused me of the notion. Some of album is a snapshot of the band’s shambolic final days, but most of it is devoted to “jokey material” from the movie and most of that is pretty terrible. The sole exception is Sid’s version of Paul Anka’s “My Way” (top), a sneering piss take on the song Sinatra made famous. After some obnoxious faux-crooning, Sid tears through song with punk aplomb. Allmusic aptly describes the performance as “inarguably remarkable” yet showing that Sid was “incapable of comprehending the irony of his situation.”

The moment of the performance itself is bathed in sad irony. I’ve always thought it showed that—had he just a little more instinct for self-preservation—we might have someday seen Sid Vicious recording an album’s worth of bratty takes on the American Songbook, but probably at McLaren’s behest. What more he might have had in him is anyone’s guess; in life he seemed unable to rise above the role McLaren assigned him in the film “Gimmick.” But he made it look good. Those familiar with Alex Cox’s definitive portrait Sid and Nancy will of course remember Gary Oldman’s recreation of Sid’s “My Way” (above). Convincing stuff, but no substitute for the real thing.

Related Content:

Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen Take Phone Calls on New York Cable TV (1978)

Watch the Sex Pistols’ Very Last Concert (San Francisco, 1978)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

In 2012, the

In 2012, the