Last year, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art wrapped up a brilliant, exhaustive exhibition about Stanley Kubrick. It was a veritable cornucopia of Kubrick memorabilia, ranging from grainy black and white photographs he took for Look magazine as a youth, to a creepy plastic Star Child from 2001: A Space Odyssey, to the blood soaked dresses of those hollow-eyed twins in The Shining. The exhibit was a massive success. It’s hard to imagine any other director, with the possible exception of Alfred Hitchcock, who would not only get an exhibit in a major art museum but also be able to pack the hall week after week.

Part of his allure, no doubt, is Kubrick’s carefully-honed public persona – a reclusive genius who controlled every element of his movies, from the font on the opening titles to the design of the poster. His movies, especially his later ones, are dense, deeply-layered works of such complexity that they continue to unpack themselves after multiple viewings. Heck, there’s an entire documentary, Room 237, that presents nine starkly different interpretations of The Shining.

Kubrick’s movies seem designed to appeal to a certain breed of obsessive film geek. So if you count yourself a member of this tribe (as I do) and you didn’t happen to catch LACMA’s exhibit, you’re in luck. The Chicago design firm Coudal Partners has created a whole online treasure trove of Kubrick ephemera. We’ve culled a few cool things from their site.

Above is a cheesy, behind-the-scenes movie for 2001. The 20-minute promo sets up the movie as if it were an episode of The Outer Limits. “It is the year 2001, you’re on your way to a space station for business,” intones the narrator. “This is but one example of what life would be like in 2001.” What follows is a series of interviews with the scientists, experts, and craftsmen involved in creating Kubrick’s vision of the future with only fleeting footage of the filmmaker himself at around the 18-minute marker. Though it does give you a lot more information on the nuts and bolts of the astronauts’ spacesuits, the short movie, one can’t help but think, is setting up the audience for disappointment. It does little to help viewers understand that the first half of 2001 is about the struggles of ape men on the plains of Africa and does even less to address the psychedelic freakout of the movie’s last reel.

Also found in Coudal’s collection is a site that has compiled all the fonts that Kubrick, a noted typography enthusiast, used in his movies. We’ve posted a couple. He liked Futura and Gothic a lot, apparently. The title card for The Shining was designed by Saul Bass.

And on this site, some genius has created sweaters, ski masks, and doormats from that odd, geometric carpet pattern from The Shining. Pre-orders have sadly closed, but hopefully they’ll start selling them again. I want the cardigan.

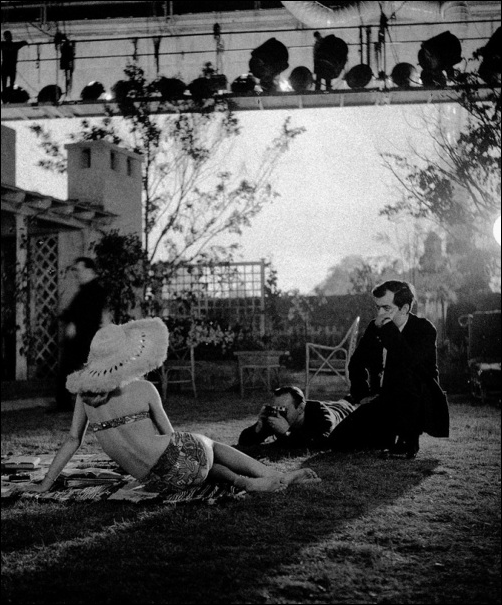

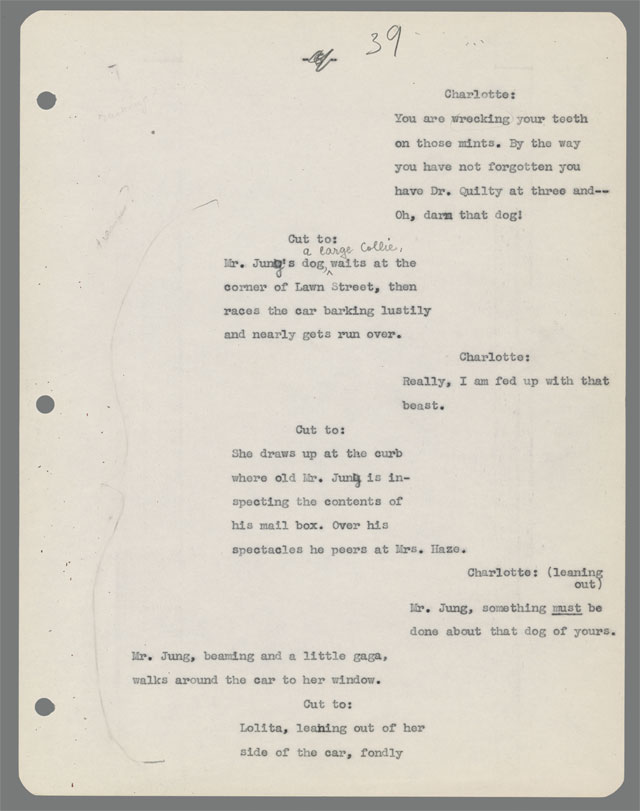

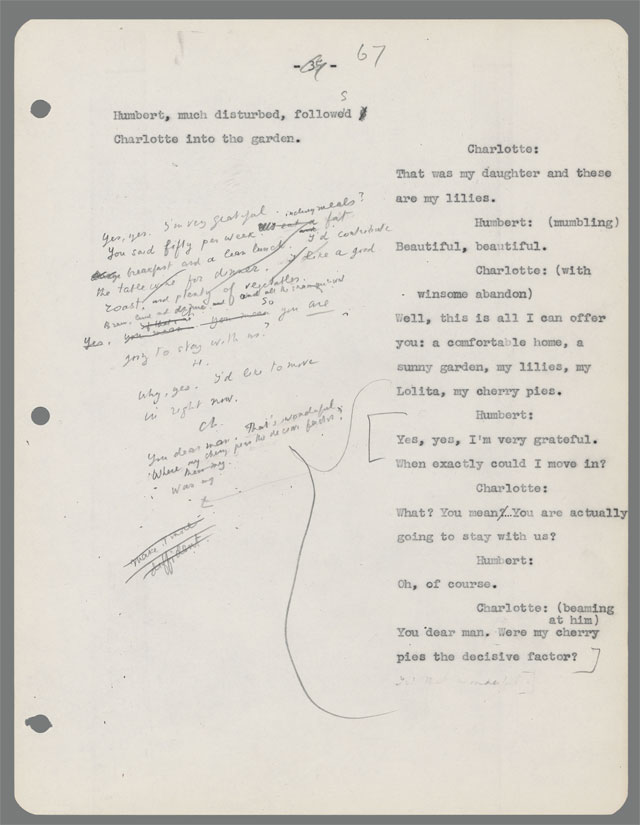

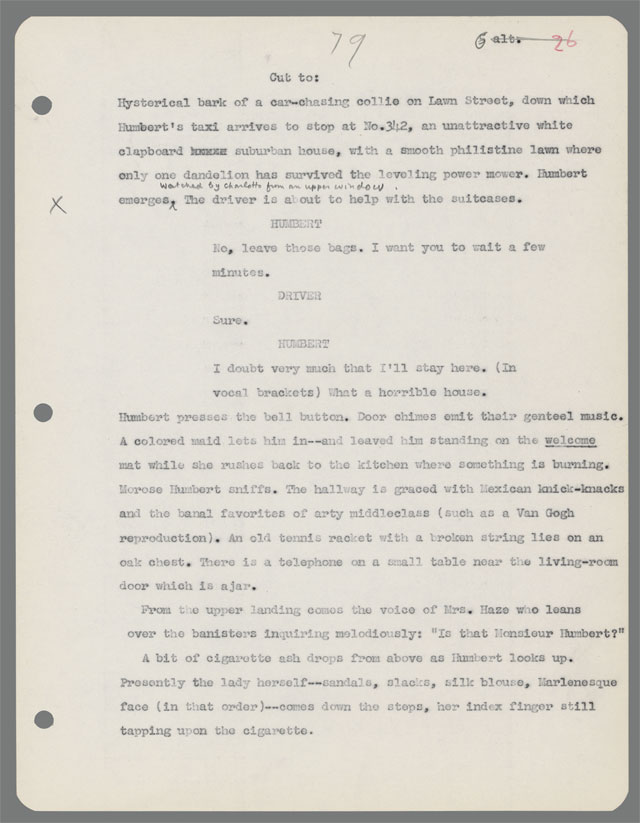

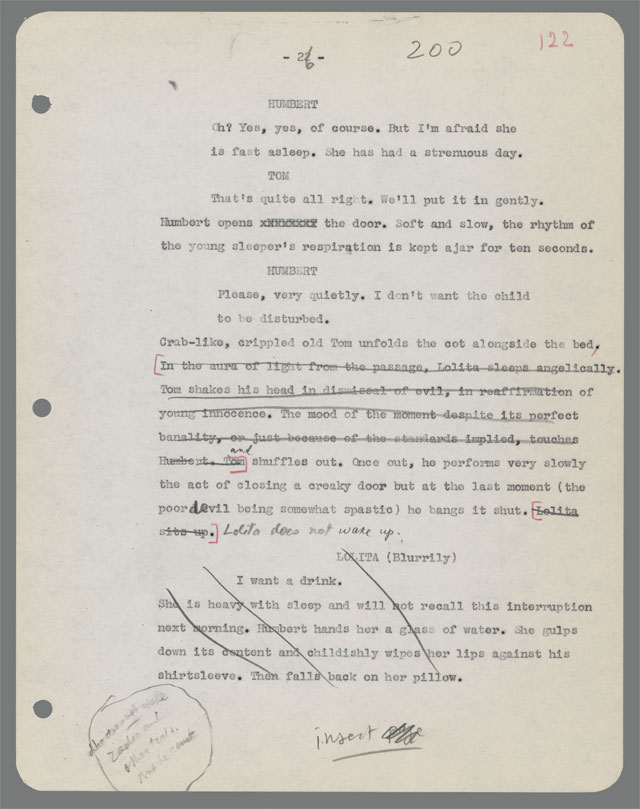

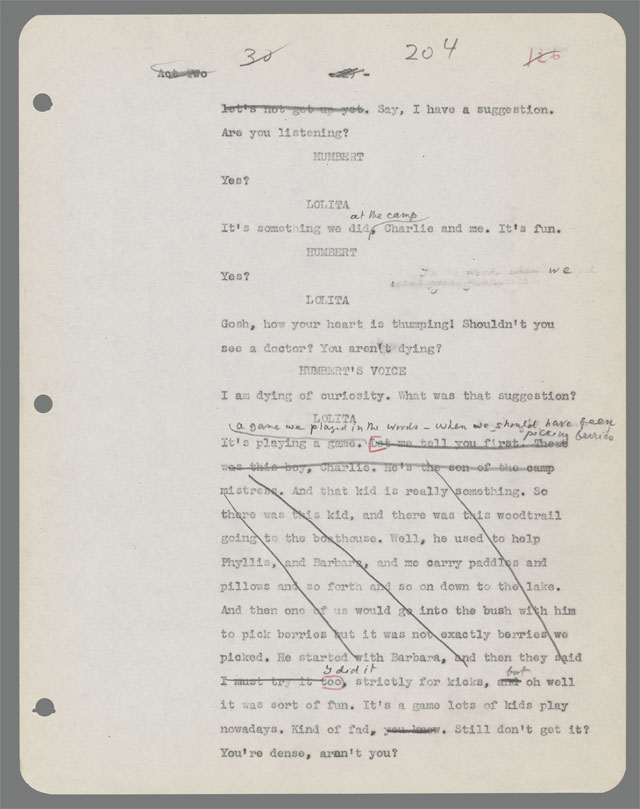

And then there’s this behind-the-scenes shot of the director and Sue Lyon on the set of Lolita accompanied by a quote from Kubrick about the actress.

“From the first, she was interesting to watch—even in the way she walked in for her interview, casually sat down, walked out. She was cool and non-giggly. She was enigmatic without being dull. She could keep people guessing about how much Lolita knew about life.”

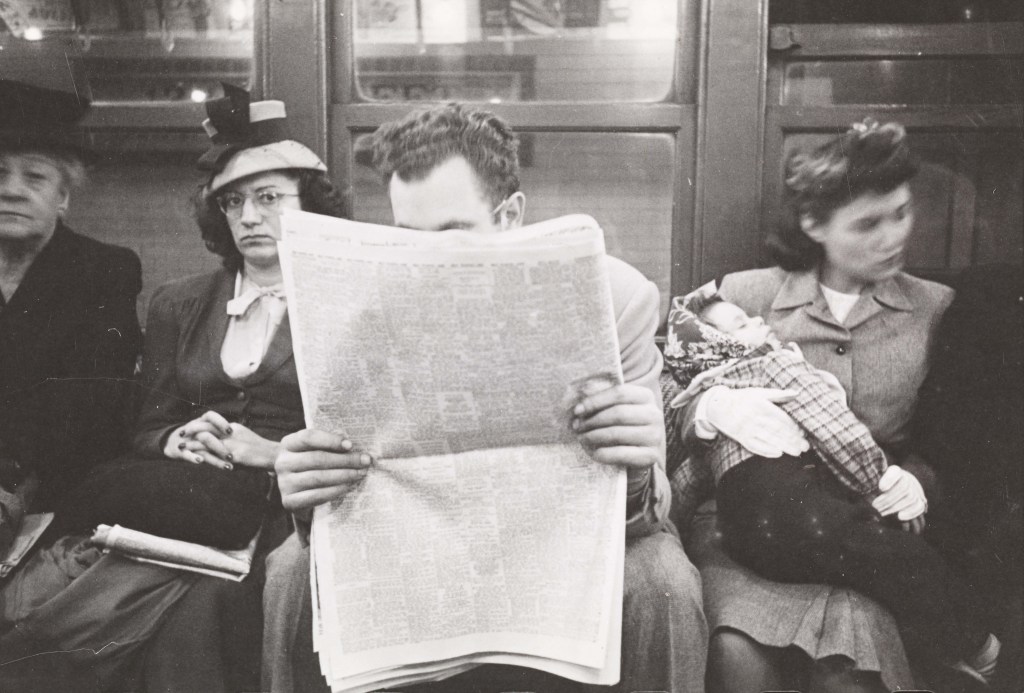

And speaking of photos, here’s a few pictures Kubrick took of the New York subway system back in 1946 for Look magazine. Compare these photos to his earliest movies like Fear and Desire and Killer’s Kiss. Both his early flicks and these pictures have the same gritty immediacy.

There is much, much more there at the Coudal Partners to keep any film nerd and Kubrick maven occupied. Check it out.

Related Content:

Fear and Desire: Stanley Kubrick’s First and Least-Seen Feature Film (1953)

Stanley Kubrick’s Daughter Shares Photos of Herself Growing Up on Her Father’s Film Sets

Stanley Kubrick’s List of Top 10 Films (The First and Only List He Ever Created)

4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow.