If you, as a filmgoer, have anything in common with me — and if you happen to live in Los Angeles as well — you’ve spent the past few weeks excited about the Andrei Tarkovsky double-bill coming up at the Quentin Tarantino-owned New Beverly Cinema. We’ve previously featured the famously (and extremely) cinephilic Tarantino’s lists of favorite films, but what about Tarkovsky? What movies did the man who made The Mirror and Nostalghia — to name only two of his most strikingly personal films, not to mention the same ones coming up at the New Beverly — look to for inspiration? Nostalghia.com has one set of answers in the form of a list Tarkovsky once gave film critic Leonid Kozlov. “I remember that wet, grey day in April 1972 very well,” writes Kozlov in a Sight and Sound article re-posted there. “We were sitting by an open window and talking about various things when the conversation turned to Otar Ioseliani’s film Once Upon a Time There Lived a Singing Blackbird.”

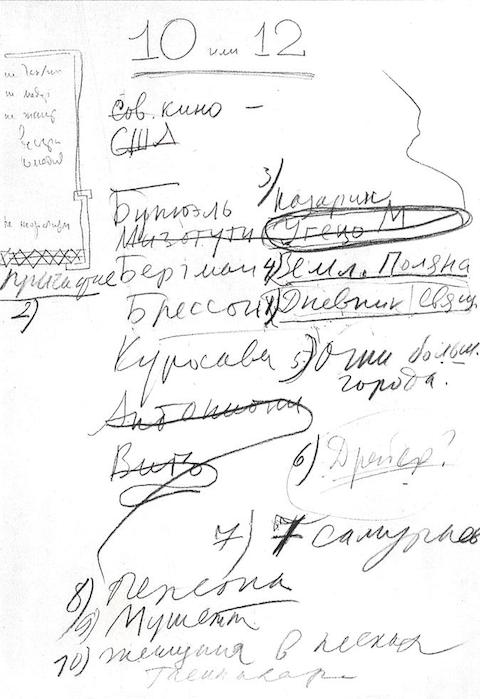

Tarkovsky struggled toward an assessment of that picture, eventually deeming it “a very good film.” Kozlov then asked the filmmaker to draw up a list of his favorites. “He took my proposition very seriously and for a few minutes sat deep in thought with his head bent over a piece of paper,” the critic recalls. “Then he began to write down a list of directors’ names — Buñuel, Mizoguchi, Bergman, Bresson, Kurosawa, Antonioni, Vigo. One more, Dreyer, followed after a pause. Next he made a list of films and put them carefully in a numbered order. The list, it seemed, was ready, but suddenly and unexpectedly Tarkovsky added another title — City Lights.” The fruit of his internal deliberations reads as follows:

- Diary of a Country Priest (Robert Bresson, 1951)

- Winter Light (Ingmar Bergman, 1963)

- Nazarin (Luis Buñuel, 1959)

- Wild Strawberries (Ingmar Bergman, 1957)

- City Lights (Charlie Chaplin, 1931)

- Ugetsu Monogatari (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1953)

- Seven Samurai (Akira Kurosawa, 1954)

- Persona (Ingmar Bergman, 1966)

- Mouchette (Robert Bresson, 1967)

- Woman of the Dunes (Hiroshi Teshigahara, 1964)

Among respected directors’ greatest-films lists, Tarkovsky’s must rank as, while certainly one of the most considered, also one of the least diverse. “With the exception of City Lights,” Kozlov notes, “it does not contain a single silent film or any from the 30s or 40s. The reason for this is simply that Tarkovsky saw the cinema’s first 50 years as a prelude to what he considered to be real film-making.” And the lack of Soviet films “is perhaps indicative of the fact that he saw real film-making as something that went on elsewhere.” Overall, we have here “not only a list of Tarkovsky’s favorite films, but equally one of his favorite directors,” especially Ingmar Bergman, who places no fewer than three times. The esteem went both ways; you may remember how Bergman once described Tarkovsky as “the greatest of them all.” Still, as cinematic mutual appreciation societies go, I suppose you couldn’t ask for two more qualified members.

If you can’t make it to the New Beverly Cinema, you can watch many of Tarkovsky’s major films (and early student films) online here.

Related Content:

Quentin Tarantino Lists His Favorite Films Since 1992

Martin Scorsese Reveals His 12 Favorite Movies (and Writes a New Essay on Film Preservation)

Stanley Kubrick’s List of Top 10 Films (The First and Only List He Ever Created)

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.