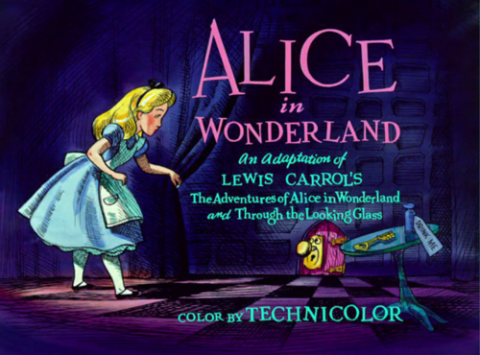

Many filmmakers have tried to adapt Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, but none, in the estimation of most enthusiasts of either Alice or animation, have fully succeeded. Maybe the episodic nature of the book gives them trouble, maybe the humor and unexpected logic of its much-celebrated “nonsense” don’t really translate from the printed word to the spoken, or maybe Carroll knew how to handle the boundary between the real and the unreal in a way no other creator can imitate. Nobody knows how many Alice adaptations have, consequently, imploded before even beginning. But when Walt Disney, not a man of small ambitions, set about to bring Carroll’s world to the silver screen, he pressed on until it became 1951’s Alice in Wonderland — about 20 years after the idea came to him in the first place.

“No story in English literature has intrigued me more than Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland,” Disney told the American Weekly in 1946. “It fascinated me the first time I read it as a schoolboy and as soon as I possibly could after I started making animated cartoons, I acquired the film rights to it.” The animator found special personal resonance in the fact that “people in his period had no time to waste on triviality, yet Carroll with his nonsense and fantasy furnished a balance between seriousness and enjoyment which everybody needed then and still needs today.”

Others attempted to bring Carroll’s nonsense and fantasy up to date on film in 1903, 1910, and 1915, and Disney himself had begun planning an aborted Alice movie with silent-era icon Mary Pickford in the early 1930s, but by the end of the Second World War, a definitive Disney adaptation had yet to appear. Enter, in the fall of 1945, Aldous Huxley: author of Brave New World, scriptwriter on previous film projects like a life of Marie Curie as well as adaptations of Pride and Prejudice and Jane Eyre, habitué of the borderlands between reality and fantasy, and, in Disney’s words, “Alice in Wonderland fiend.” Disney needed such a fiend, having started to fear that his desired modernization of the material might upset the Carroll faithful.

Huxley’s script, a combination of live action and animation, deals with the friendship between the Oxford don Charles Dodgson (known, of course, by the pen name Lewis Carroll), held back from attaining his dreamed-of life as a librarian by the university’s stern vice chancellor, and Alice (based upon Alice Liddell, the real-life inspiration for Carroll’s fictional Alice), held back from all things impractical by her even sterner governess. Though Huxley enjoyed doing the work, Disney found it “too literary,” and nothing of it made it into the 1951 movie. Even then, the final product displeased the exacting animation visionary, as it still does quite a few Disney fans.

While the full text of Huxley’s screenplay hasn’t survived, and much of what Huxley wrote to produce it burnt up in a 1961 house fire, you can read a thorough synopsis of it and more of the backstory on the project at Mouseplanet. For even greater detail, see also “Huxley’s ‘Deep Jam’ and the Adaptation of Alice in Wonderland,” an essay by David Leon Higdon and Phill Lerhman in the Huxley volume of Harold Bloom’s Modern Critical Views series.

Related Content:

See Salvador Dali’s Illustrations for the 1969 Edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Alice in Wonderland: The Original 1903 Film Adaptation

Lewis Carroll’s Photographs of Alice Liddell, the Inspiration for Alice in Wonderland

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.