In 1968, years before American Graffiti, Raiders of the Lost Ark and, shudder, the Star Wars prequels, George Lucas was a struggling filmmaker with a couple of experimental films movies under his belt. His short Electronic Labyrinth THX 1138 4EB took first prize at the National Student Film Festival, but he had yet to make the plunge into feature films. So he did what many other artists and creative types did in the past – he glommed onto a more successful friend.

The friend in this case was Francis Ford Coppola, who by 1968 had already directed three features and was starting production of his latest movie, The Rain People. Lucas talked his friend into letting him shoot a behind-the-scenes documentary about the production. The resulting doc, Filmmaker –A Diary By George Lucas, is a fascinating document of the early days of New Hollywood and the struggles of getting an independent movie made. You can watch it above.

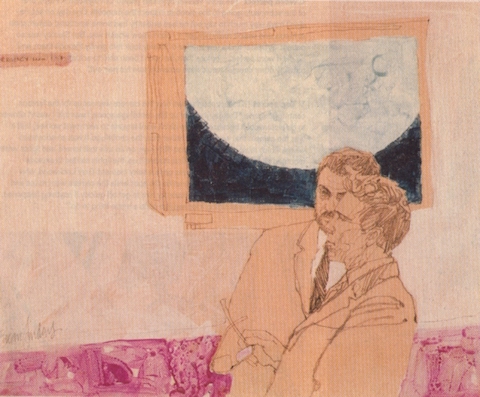

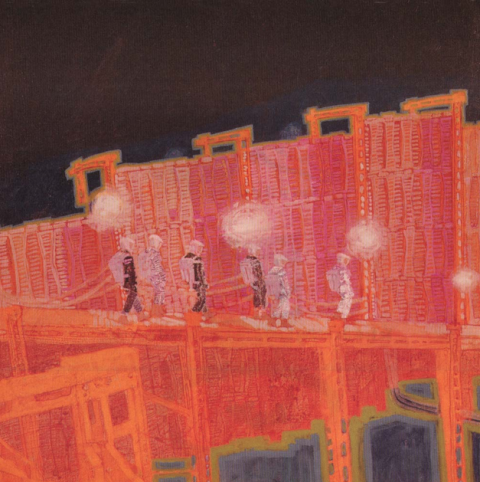

Shot in a cinéma vérité matter, Lucas captures Coppola at his most charming, creative and passionate – dealing with the studios over the phone, consulting with a baby-faced James Caan on set and struggling to shoot a scene while battling the stomach flu. He was even forced to shave his trademark beard so as not to upset any of the local anti-hippy constabularies. The film shows Coppola making up the film as he went along. At one point, he re-writes a scene to incorporate an actual local parade. Filmmaker makes an interesting contrast with that other Coppola documentary, Hearts of Darkness, made on the set of Apocalypse Now. Here he’s filled with a youthful vigor that in Hearts, deep in the jungles of the Philippines, has transformed into half-mad egomania. Of course, the shoot for Rain People wasn’t anywhere near as epic or disastrous as Apocalypse.

On set, Lucas shot and recorded sound for the doc all by himself and generally made himself as unobtrusive as possible. “George was around in a very quiet way,” recalled Rain People producer Ron Colby. “You’d look around and suddenly there’d be George in a corner with his camera. He’d just kind of drift around.”

The movie proved to be valuable for Lucas’s confidence as a filmmaker. He later described making the movie as “more therapy than anything else. “At night, after production had wrapped for the day, Lucas would go off to write the script to his first feature THX-1138.

Filmmaker finally premiered in 1977, the year that Lucas released Star Wars and completely stepped out from the shadow of his friend and mentor Coppola.

An alternative version can be found on Youtube here. Other great films can be found in our rich collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Via Devour/Kitbashed

Related Content:

How Star Wars Borrowed From Akira Kurosawa’s Great Samurai Films

Freiheit, George Lucas’ Short Student Film About a Fatal Run from Communism (1966)

Watch the Very First Trailers for Star Wars, The Empire Strikes Back & Return of the Jedi (1976–83)

Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyers Break Down Star Wars as an Epic, Universal Myth

Hundreds of Fans Collectively Remade Star Wars; Now They Remake The Empire Strikes Back

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of badgers and even more pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.