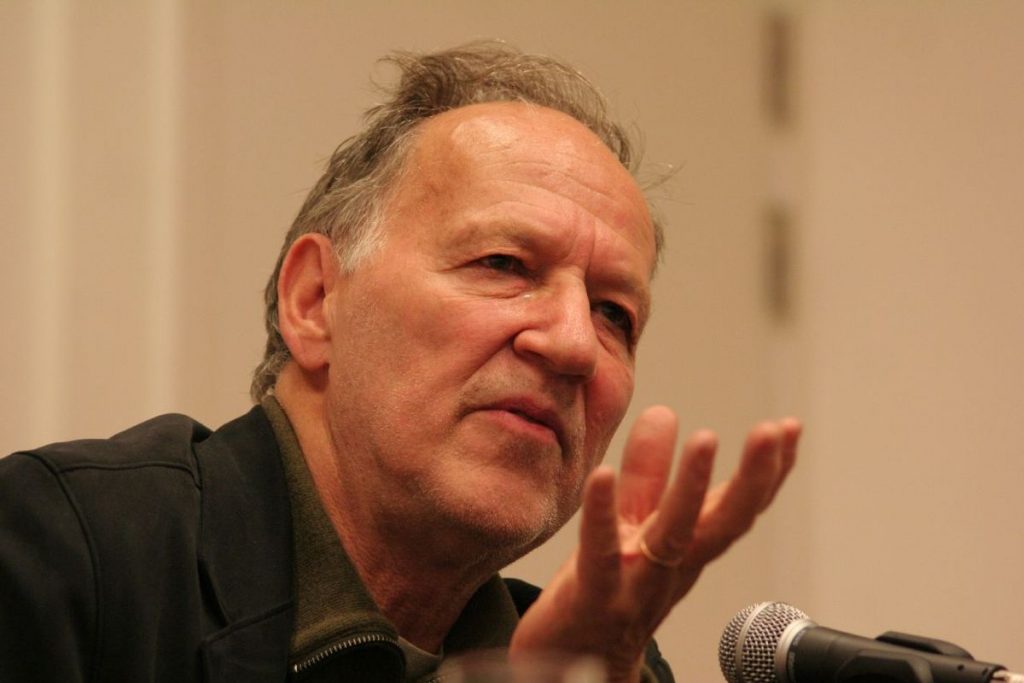

Slavoj Žižek – the world’s most famous Slovenian, the “Elvis of cultural theory” – readily admits that he’s a big fan of movies. After all, there are few better ideological delivery systems out there than cinema and Žižek is fascinated with ideology. In his documentary The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology, he parses some beloved favorites in unexpected ways. So Taxi Driver is not only an unofficial remake of The Searchers but also echoes America’s recent foreign policy blunders in the Middle East? Okay. So Titanic has parallels with the Soviet propaganda movie The Fall of Berlin? Sure. Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight, at its heart, articulates some very cynical notions of government? Actually, I sort of suspected that one. Žižek’s tendency to make wild, surprising rhetorical leaps and his penchant for dropping nods to pop culture alongside references to Karl Marx and Jacques Lacan have turned him into that rarest of people – a celebrity philosopher.

Last fall, Žižek stopped by the office of The Criterion Collection where he rattled off some of his favorite movies from its library. His commentary is incisive, fascinating, occasionally flip and often funny. As it turns out, Žižek is not a fan of Milan Kundera; he is one of the very few people out there who prefers Roberto Rossellini’s late films over his early Italian Neo-Realist masterpieces like Rome, Open City; and he ended up being a personal inspiration for Ang Lee’s film, The Ice Storm. You can watch him talk in the video above. Below is the film list, along with some choice quotes.

- Trouble in Paradise (1932) – dir. Ernst Lubitsch

“It’s the best critique of Capitalism.”- Sweet Smell of Success (1957) – dir. Alexander Mackendrick

“It’s a nice depiction of the corruption of the American press.”- Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) – dir. Peter Weir

“I simply like early Peter Weir movies. … It’s like his version of Stalker.”- Murmur of the Heart (1971)- dir. Louis Malle

“It’s one of those nice gentle French movies where you have incest. Portrayed as a nice secret between mother and son. I like this.”

- The Joke (1969) – dir. Jaromil Jireš

“The Joke is the first novel by Milan Kundera and I think it’s his only good novel. After that it all goes down.”- The Ice Storm (1997) – dir. Ang Lee

“I have a personal attachment to this film. When James Schamus was writing the scenario, he told me he was reading a book of mine and that my theoretical book was inspiration [sic]. So it’s personal reason but I also loved the movie.”- Great Expectations (1946) dir. David Lean

“I am simply a great fan of Dickens.”- Rossellini’s History Films (Box Set) — The Age of the Medici (1973), Cartesius (1974), Blaise Pascal (1972)

“Rossellini’s history films, I prefer them. These late, long boring TV movies. I think that the so-called great Rossellinis, for example German Year Zero and so on, they no longer really work. I think this is the Rossellini to be rehabilitated.”- City Lights (1931) – dir. Charlie Chaplin

“What is there to say? This is one of the greatest movies of all times.”- Carl Theodor Dreyer Box Set — Day of Wrath (1943), Ordet (1955), Gertrud (1964)

“It’s more out of my love for Denmark. It’s nice to know already in the ‘20s and ‘30s, Denmark was already a cinematic superpower.- Y Tu Mamá También (2002) – dir. Alfonso Cuáron

“This is for obvious personal reason. I do the comment. [He did the DVD Commentary for the movie] Although, I must say that my favorite Cuáron is Children of Men.”- Antichrist (2009) – dir. Lars Von Trier

“I will probably not like it, but I like Von Trier. It is simply a part of a duty.”

Žižek goes on to say that he oftentimes enjoys the DVD commentary of a movie more than the actual film. “I am a corrupted theorist. Screw the movie. I like to learn all around the movie.”

And below you can watch Žižek’s take on John Carpenter’s overlooked gem, and leftist parable, They Live!

Related Content:

Good Capitalist Karma: Zizek Animated

A Shirtless Slavoj Žižek Explains the Purpose of Philosophy from the Comfort of His Bed

After a Tour of Slavoj Žižek’s Pad, You’ll Never See Interior Design in the Same Way

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of badgers and even more pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.