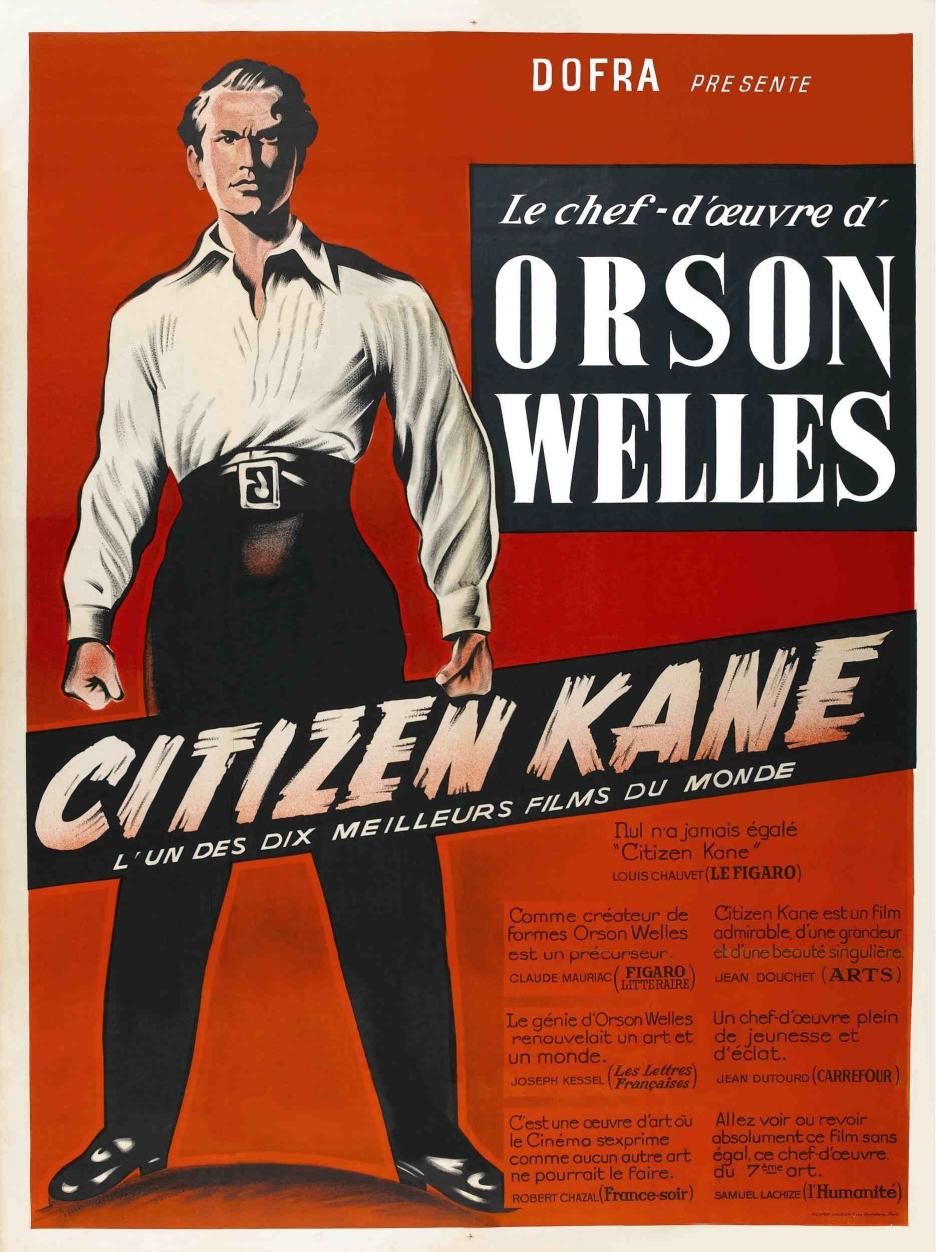

You may recall our posting last year of Jorge Luis Borges’ review of Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane — surely one of the most Open Culture-worthy intersections of 20th century luminaries ever to occur. Borges described Welles’ masterwork as possessed of one side that, “pointlessly banal, attempts to milk applause from dimwits,” and another, a “kind of metaphysical detective story” whose “subject (both psychological and allegorical) is the investigation of a man’s inner self, through the works he has wrought, the words he has spoken, the many lives he has ruined.” On the whole, the author of Labyrinths called the picture “not intelligent, though it is the work of genius.”

Not long after our post, the Paris Review’s Dan Piepenbring wrote one that also quoted another, later review of Citizen Kane by none other than Jean-Paul Sartre:

Kane might have been interesting for the Americans, [but] it is completely passé for us, because the whole film is based on a misconception of what cinema is all about. The film is in the past tense, whereas we all know that cinema has got to be in the present tense. ‘I am the man who is kissing, I am the girl who is being kissed, I am the Indian who is being pursued, I am the man pursuing the Indian.’ And film in the past tense is the antithesis of cinema. Therefore Citizen Kane is not cinema.

The 1945 review originally ran in high-minded film journal L’Écran français under the headline “Quand Hollywood veut faire penser … Citizen Kane d’Orson Welles,” or, “When Hollywood Wants to Make Us Think … Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane.” According to The Writings of Jean-Paul Sartre: A Bibliographical Life, “in re-reading this [review], which he did not remember at all, Sartre hardly recognized his style and expressed some doubt about the authenticity of his signature. On the other hand, he did find in it the ideas Citizen Kane suggested to him when he first saw it in the United States. After he saw the film again in France, Sartre had a slightly more favorable opinion of it, but he still thinks it is undoubtedly no masterpiece.”

But at the time, writes Simon Leys, “the impact of this condemnation was devastating. The Magnificent Ambersons was shown soon afterwards in Paris but failed miserably. The cultivated public always follows the directives of a few propaganda commissars: there is much more conformity among intellectuals than among plumbers or car mechanics.” Or at least the cultivated public did so in 1940s Paris; the mechanics of culture have changed somewhat since then, but as far as Citizen Kane goes, high-profile opinions about it have grown only more positive over time. Sure, Vertigo recently knocked it down a peg in the Sight and Sound poll, but that just makes me wonder what Sartre thought of Hitchcock’s masterwork — a film that might have had a resonance or two in the mind of an existentialist.

Related Content:

Jorge Luis Borges, Film Critic, Reviews Citizen Kane — and Gets a Response from Orson Welles

Orson Welles Explains Why Ignorance Was His Major “Gift” to Citizen Kane

Jean-Paul Sartre Rejects the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1964: “It Was Monstrous!”

Jean-Paul Sartre Breaks Down the Bad Faith of Intellectuals

Human, All Too Human: 3‑Part Documentary Profiles Nietzsche, Heidegger & Sartre

Download Walter Kaufmann’s Lectures on Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, Sartre & Modern Thought (1960)

Colin Marshall writes on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.