The Gandhi of history doesn’t line up with the Gandhi of legend, just as the beatified Mother Teresa presents a very different picture in certain astute critics’ estimation. But as with most saints, ancient and modern, people tend to ignore Gandhi’s many contradictions and troublingly racist and casteist views. He comes to us more as myth and martyr than deeply flawed human individual. An indispensable part of the mythmaking, Richard Attenborough’s 1982 biopic, Gandhi, may be “over-sanitized,” as The Guardian writes, but Ben Kingsley’s performance as the anti-colonial leader is genuinely “sublime” in his evocation of Gandhi’s “intensity… wit and even the distinctive, determined walk.” It’s these personal qualities—and of course Gandhi’s defeat of the largest empire on the planet with nonviolent action and a spiritual philosophy—that continue to inspire movements for justice and civil rights.

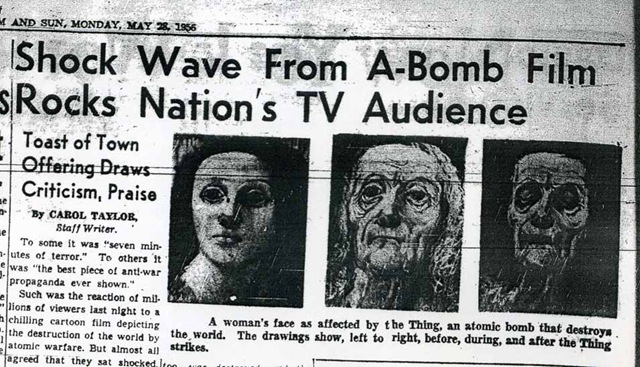

We see a little of that determined walk in the short newsreel interview above, the very first “talking picture” made of Gandhi, and we also hear his intensity and wit, though much subdued by his physical frailty after years of fasting. Taken in 1947 by Fox Movietone News, the film marks a pivotal period in the Indian leader’s life. Very shortly after this Parliament passed the Indian Independence Act. That year also marked the start of a bloody new struggle, instigated by another colonial intervention, as the British partitioned India into two warring countries, an act so poignantly dramatized in Salmon Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children.

This year of turmoil was also Gandhi’s last; he was assassinated in 1948 by a Hindu nationalist who accused him of siding with Pakistan. In the interview, we hear what we might think of as some of Gandhi’s final public pronouncements on such subjects as child marriage, prohibition, his deeply held convictions about an authentic Indian cultural identity, and the lengths that he would go for his country’s independence. At the end of the short interview, the American reporter asks Gandhi, presciently, “would you be prepared to die in the cause of India’s Independence?” to which Gandhi replies, “this is a bad question.”

Related Content:

Albert Einstein Expresses His Admiration for Mahatma Gandhi, in Letter and Audio

Hear Gandhi’s Famous Speech on the Existence of God (1931)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness