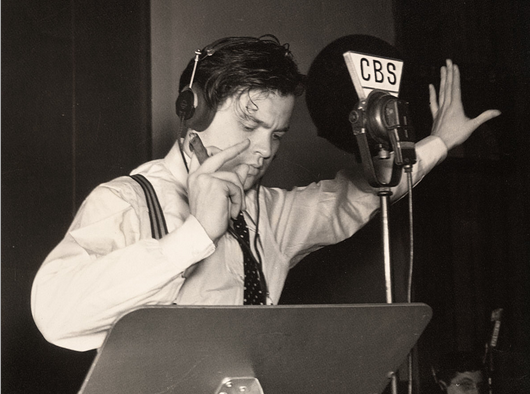

“One of the first video recordings of a David Lynch interview dates from 1979,” writes The New Yorker’s Dennis Lim. “The twenty-minute black-and-white segment was produced for a television course at the University of California, Los Angeles, and conducted in the oil fields of the Los Angeles Basin, one of the locations that constituted the barren wasteland of his first feature, Eraserhead (1977).” And it is Eraserhead these UCLA students, in what Lim calls “the moment of Lynch’s first brush with cult fame,” want to know about, putting a variety of questions to the young filmmaker, and putting his ability to answer them concretely to the test.

You may well learn more about Eraserhead in the theater-lobby audience responses collected for the video, wherein the viewers — viewers, remember, from a now hard-to-imagine time when the name David Lynch carried no meaning at all — exiting a screening express reactions ranging from great pleasure (some of them boast of having seen it as many as eight times already) to predictable bewilderment (“I’ve gotta think about it for a while”) and even more predictable distaste: “The weirdest thing I’ve ever seen.” “It’s terrible. I didn’t like it.” “Some inane, bizarre person with a disturbed mind wrote that film.” But does the man standing there submitting to a student interview in the middle of an oil field seem so bizarre, so disturbed?

Some of Lynch’s answers, as when he describes Eraserhead as “not like thrown-together abstract” but “meant-to-be-that-way abstract,” may strike you as inane at first, but certainly nothing he says crosses the line from inanity to insanity. In the almost 40 years since the film’s first showing, Eraserhead has grown more artistically divisive even as its fan base spans a wider and wider range of generations and nationalities. Both its promoters and its detractors may sometimes wonder if even Lynch himself understands it, but to my mind, this early interview hints that he does. He made what he calls “an open-feeling film,” a fount of an infinitude of interpretations, and for that reason an enduring work of art. And he meant it to be that way.

Related Content:

The Paintings of Filmmaker/Visual Artist David Lynch

David Lynch’s Unlikely Commercial for a Home Pregnancy Test (1997)

David Lynch Teaches You to Cook His Quinoa Recipe in a Weird, Surrealist Video

What David Lynch Can Do With a 100-Year-Old Camera and 52 Seconds of Film

Colin Marshall writes elsewhere on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, and the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future? Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.