If you aren’t seriously disturbed, even alarmed, that we in the U.S. have a presidential candidate from a major political party who succeeds by whipping up xenophobic fervor and telling us the country must not only reinstitute torture, but must do “the unthinkable”… well…. I don’t really know what to say to you. Perhaps more symptom than cause of a global turn toward tribal hatred, the GOP candidate has lent his name to a phenomenon characterized by cultish devotion to an authoritarian strongman, serial falsehood, and easy, uncritical scapegoating. We needn’t look far back in time to see the historical analogues, whether in the early 20th century, at the end of the 19th, or during any number of historical moments before and after.

We also needn’t look very far back to find a history of resistance to authoritarian bigotry, and not only from Civil Rights campaigners and leftists, but also, as you can see above, from the U.S. War Department. In 1947, the Department released the short propaganda film, “Don’t Be a Sucker!”, aimed at middle-class American Joes. Shot at Warner Studios, the film opens with some typical noirish crime scenarios, complete with convincingly noir lighting and camera angles, to visually set up the character of the “sucker” who gets taken in by sinister but seductive characters—“people who stay up nights trying to figure out how to take away” what the everyman has. What do naïve potential marks in this analogy have to lose? American plenty: “plenty of food, big factories to make things a man can use, big cities to do the business of a big country, and people, lots of people.”

“People,” the narrator says, working the farms and factories, digging the mines and running the businesses: “all kinds of people. People from different countries with different religions, different colored skins. Free people.” Is this disingenuous? You bet. We’re told this aggregate of people is “free to vote”—and we know this to be largely untrue in practice for many, necessitating the Voting Rights Act almost twenty years later. Free to “pick their own jobs”? Employment discrimination, segregation, and sexism effectively prevented that for millions. But the sentiments are noble, even if the facts don’t fully fit. As our average Joe wanders along, contemplating his advantages, he happens upon a reactionary streetcorner demogague haranguing against foreigners, African-Americans, Catholics, and Freemasons (?) on behalf of “real Americans.” Sounds plenty familiar.

The voice of reason comes from a naturalized Hungarian professor who witnessed the rise of Nazism in Berlin and who explains to our everyman the strategy of fanatics and fascists—divide and rule. “We human beings are not born with prejudices,” says the wise professor, “always they are made for us. Made by someone who wants something. Remember that when you hear this kind of talk. Somebody’s going to get something out of it. And it isn’t going to be you.” The remainder of the film mostly consists of the Hungarian professor’s recollections of how the Nazis won over ordinary Germans.

“Don’t Be a Sucker!” uses a clever rhetorical strategy, appealing to the self-interest and vanity of the everyman while couching that appeal in egalitarian values. The very recent historical example of fascist Europe carries significant weight, where too often today that history gets treated like a joke, turned into crude and muddled memes. This film would have had real impact on the viewing audience, who would have seen it before their feature in theaters across the country.

It’s worth noting that this film came out during a period of increasing American prosperity and comparative economic equity. The jobs “Don’t Be a Sucker!” lists with pride have disappeared. Today’s everyman, we might say, has even more reason for susceptibility to the demagogue’s appeals. The Internet Archive notes an irony here “in the light of Cold War anti-Communist politics, which really came into their own in the year this film was made.” The streetcorner populist calls to mind people like Joseph McCarthy and J. Edgar Hoover (and he looks like George Wallace)—powerful government authorities who cast suspicion on every movement for Civil Rights and social equality.

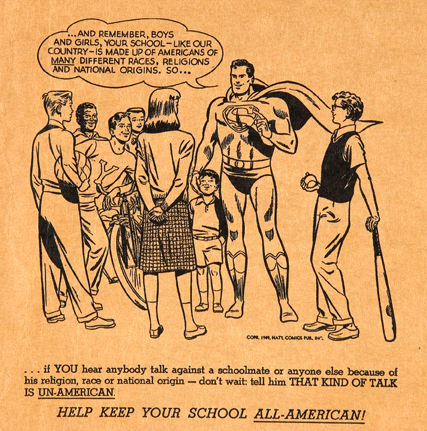

“Don’t Be a Sucker!” may seem like an outlier, but it’s reminiscent of another piece of patriotic, anti-racist-and-religious-bigotry propaganda—the Superman cartoon above, which first appeared in 1949, distributed to school children as a book cover by something called The Institute for American Democracy. You may have seen versions of a full-color poster, reprinted in subsequent years. Here, Superman expresses the same egalitarian values as “Don’t Be a Sucker!” only instead of calling racism a con-job, he calls it “Un-American,” using the favorite denunciation of HUAC and other anti-Communist groups.

History and the present moment may often prove otherwise—showing us just how very American racism and bigotry can be, but so too are numerous counter-movements on the left and, as these examples show, from more conservative, establishment corners as well.

“Don’t Be a Sucker!” will be added to our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

Bertolt Brecht Testifies Before the House Un-American Activities Committee (1947)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness