Despite living for only 37 years, and within that having a career that lasted for only fifteen, the German auteur Rainer Werner Fassbinder created so prolifically that his final list of accomplishments includes directing forty feature films, three shorts, and two television series, as well as appearing in 36 different roles as an actor — to say nothing of his works in other media and his considerable influence on subsequent generations of filmmakers around the world. Sheer productivity aside, many of these works have either stood the test of time, like The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant and Berlin Alexanderplatz or, like philosophical science fiction World on a Wire, enjoyed recent rediscoveries.

What could have inspired in Fassbinder such unrelenting creativity? His list of ten favorite films, drawn up a year before his death in 1982, provides some clues. “Fassbinder’s very favorite was Visconti’s The Damned, a visually sumptuous panorama of societal collapse and decay in Third Reich Germany and no doubt an influence on the German auteur’s own “BRD Trilogy,” in particular the bawdy, bordello-set Lola,” writes Indiewire’s Ryan Lattanzio. He also “loved Max Ophuls’ 1955 Lola Montes, the sad story of a kept woman shot in the kind of gloriously rendered color Fassbinder would later employ in his own work. As with many top 10 lists compiled by confrontational filmmakers, Pasolini’s beautifully ugly descent into hell Salò was also close to his heart.”

Fassbinder’s final favorite-films list runs, in full, as follows:

- The Damned (1969, Dir: Luchino Visconti)

- The Naked And the Dead (1958, Dir: Raoul Walsh)

- Lola Montes (1955, Dir: Max Ophuls)

- Flamingo Road (1949, Dir: Michael Curtiz)

- Salò, or the 120 Days Of Sodom (1975, Dir: Pier Paolo Pasolini)

- Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953, Dir: Howard Hawks)

- Dishonored (1931, Dir: Josef von Sternberg)

- The Night Of The Hunter (1955, Dir: Charles Laughton)

- Johnny Guitar (1954, Dir: Nicholas Ray)

- The Red Snowball Tree (1973, Dir: Vasili Shukshin)

If one quality unites all of Fassbinder’s motion pictures of choice, from all the aforementioned to the stark, near-Expressionist noir of Night of the Hunter to the superhumanly snappy comedy of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes to the Western genre reinvention, highly appreciated in Europe, of Johnny Guitar, it might well be vividness. All of these movies, each in their own way, allowed Fassbinder to release the vividness — and cinema history has remembered him as a master of the vivid as well as the visceral — resident in his imagination. Alas, no matter how much he managed to realize, a great deal more of it surely passed away with him.

Related Content:

Akira Kurosawa’s List of His 100 Favorite Movies

Martin Scorsese Reveals His 12 Favorite Movies (and Writes a New Essay on Film Preservation)

Stanley Kubrick’s List of Top 10 Films (The First and Only List He Ever Created)

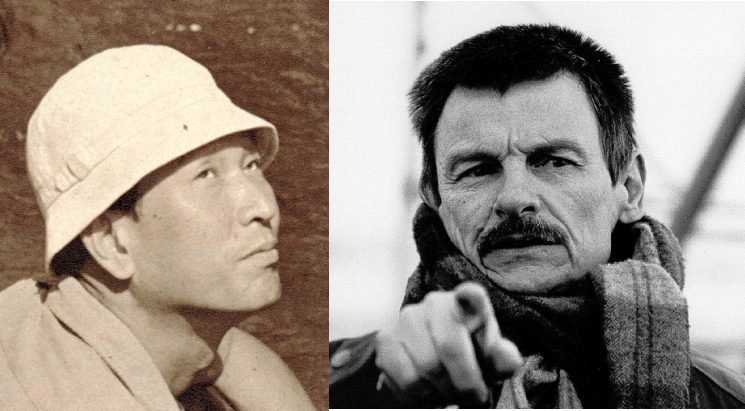

Andrei Tarkovsky Creates a List of His 10 Favorite Films (1972)

Susan Sontag’s 50 Favorite Films (and Her Own Cinematic Creations)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.