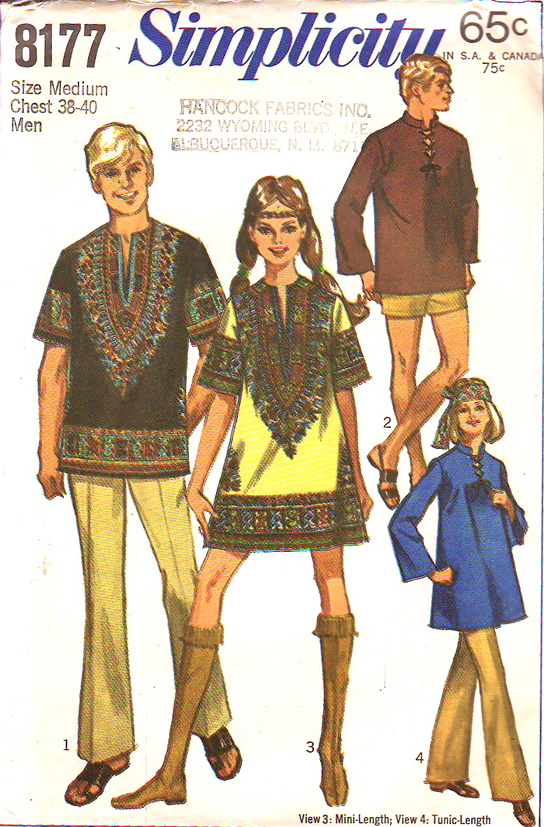

Both the fashion and art worlds foster the creation of rarified artifacts inaccessible to the majority of people, often one-of-a-kind pieces that exist in specially-designed spaces and flourish in cosmopolitan cities. Does this mean that fashion is an art form like, say, painting or photography? Doesn’t fashion’s ephemeral nature mark it as a very different activity? We might consider that we can ask many of the same questions of haute couture as we can of fine art. What are the social consequences of taking folk art forms, for example, out of their cultural context and placing them in gallery spaces? What is the effect of tapping street fashion as inspiration for the runway, turning it into objects of consumption for the wealthy?

Such questions should remind us that fashion and the arts are embedded in human cultural and economic history in some very similar ways. But they are also very different social practices. Much like trends in food (both fine dining and cheap consumables) fashion has long been implicated in the spread of markets and industries, labor exploitation, environmental degradation, and even microbes. As Jason Daley points out at Smithsonian, “The craze for silk in ancient Rome helped spawn the Silk Road, a fashion for feathered hats contributed to the first National Wildlife Refuges. Fashion has even been wrapped up in pandemics and infectious diseases.”

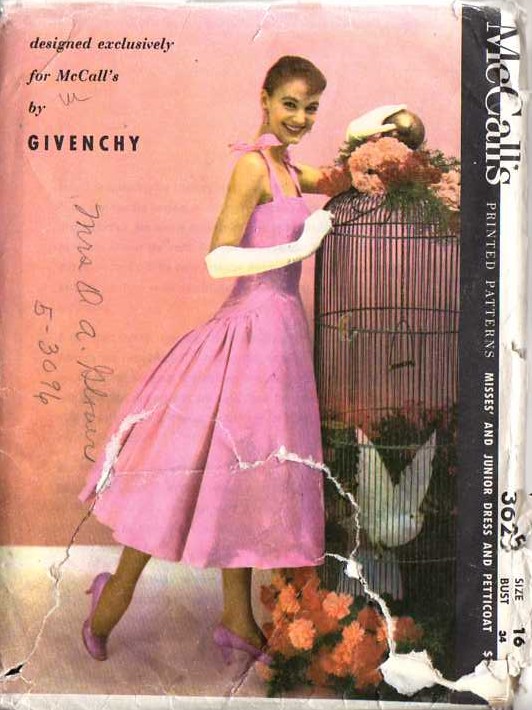

So how to tell the story of a human activity so deeply embedded in every facet of world history? Expansively. Google Arts & Culture has attempted to do so with its “We wear culture” project. Promising to tell “the stories behind what we wear,” the project, as you can see in the teaser video at the top, “travelled to over 40 countries, collaborating with more than 180 cultural institutions and their world-renowned historians and curators to bring their textile and fashion collections to life.” Covering 3,000 years of history, “We wear culture” uses video, historical images, short quotes and blurbs, and fashion photography to create a series of online gallery exhibits of, for example, “The Icons,” profiles of designers like Oscar de la Renta, Coco Chanel, and Issey Miyake.

Another exhibit “Fashion as Art” includes a feature on Florence’s Museo Salvatore Ferragamo, a gallery dedicated to the famous designer and containing 10,000 models of shoes he created or owned. Asking the question “is fashion art?”, the exhibit “analyses the forms of dialogue between these two worlds: reciprocal inspirations, overlaps and collaborations, from the experiences of the Pre-Raphaelites to those of Futurism, and from Surrealism to Radical Fashion.” It’s a wonder they don’t mention the Bauhaus school, many of whose resident artists radicalized fashion design, though their geometric oddities seem to have had little effect on Ferragamo.

As you might expect, the emphasis here is on high fashion, primarily. When it comes to telling the stories of how most people in the world have experienced fashion, Google adopts a very European, supply side, perspective, one in which “The impact of fashion,” as one exhibit is called, spans categories “from the economy and job creation, to helping empower communities.” Non-European clothing makers generally appear as anonymous folk artisans and craftspeople who serve the larger goal of providing materials and inspiration for the big names.

Cultural historians may lament the lack of critical or scholarly perspectives on popular culture, the distinct lack of other cultural points of view, and the intense focus on trends and personalities. But perhaps to do so is to miss the point of a project like this one—or of the fashion world as a whole. As with fine art, the stories of fashion are often all about trends and personalities, and about materials and market forces.

To capitalize on that fact, “We wear culture” has a number of interactive, 360 degree videos on its YouTube page, as well as short, advertising-like videos, like that above on ripped jeans, part of a series called “Trends Decoded.” Kate Lauterbach, the program manager at Google Arts & Culture, highlights the videos below on the Google blog (be aware, the interactive feature will not work in Safari).

- Find out how Chanel’s black dress made it acceptable for women to wear black on any occasion (Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, France — 1925)

- Step on up—way up—to learn how Marilyn Monroe’s sparkling red high heels became an expression of empowerment, success and sexiness for women (Museo Salvatore Ferragamo from Florence, Italy — 1959)

- See designer Vivienne Westwood’s unique take on the corset, one of the most controversial garments in history (Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK — 1990)

- Discover the Comme des Garçons sweater and skirt with which Rei Kawakubo brought the aesthetics and craftsmanship of Japanese design onto the global fashion stage (Kyoto Costume Institute, Kyoto, Japan — 1983)

Does the project yet deliver on its promise, to “tell the stories behind what we wear”? That all depends, I suppose, on who “we” are. It is a very valuable resource for students of high fashion, as well as “a pleasant way to lose an afternoon,” writes Marc Bain at Quartz, one that “may give you a new understanding of what’s hanging in your own closet.”

“We wear culture” features 30,000 fashion pieces and more than 450 exhibits. Start browsing here.

Related Content:

Kandinsky, Klee & Other Bauhaus Artists Designed Ingenious Costumes Like You’ve Never Seen Before

1930s Fashion Designers Predict How People Would Dress in the Year 2000

Punk Meets High Fashion in Metropolitan Museum of Art Exhibition PUNK: Chaos to Couture

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness