TikTok, the short-form video-sharing platform, is an arena where the young dominate — last summer, The New York Times reported that over a third of its 49 million daily users in the US were aged 14 or younger.

Yet somehow, a fully grown medieval peasant has become one of its most compelling presences, breezily sharing his yoga regimen, above, his obsession with tassels and ornate sleeves, and the Metropolitan Transit Authority’s plans to upcycle his era’s torture devices as New York City subway exit gates.

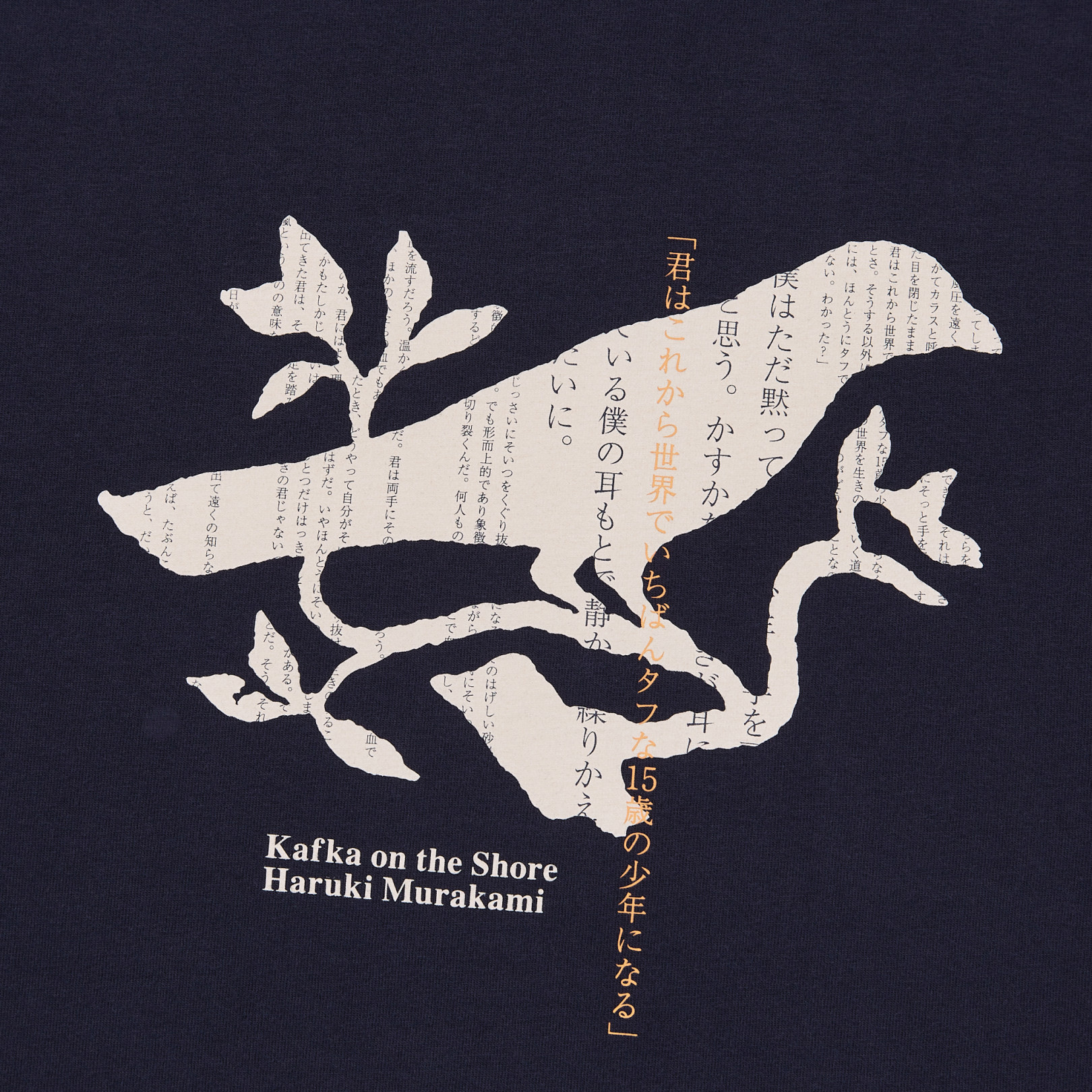

30-year-old Brooklyn-based artist Tyler Gunther views his creation, Greedy Peasant, as “the manifestation of all the strange medieval art we now enjoy in meme form”:

Often times medieval history focuses on royals, wars, popes and plagues. With this peasant guide, we get to experience the world through the lens of a queer artist who is just trying to make sure everyone is on time for their costume fittings for the Easter pageant.

Earlier, Gunther’s medieval fixation found an outlet in comics that he posted to Instagram.

Then last February, he found himself quarantining in an Australian hotel room for 2 weeks prior to performing in the Adelaide Festival as part of The Plastic Bag Store, artist Robin Frohardt’s alternately hilarious and sobering immersive supermarket installation:

My quarantine plans had been to work on a massive set of illustrations and teach myself the entire Adobe Creative Suite. Instead I just wandered from one corner of the hotel room to the next and stared at the office building directly outside my window. About 4 days in, Robin texted, “Now is your time to make a TikTok.” I had avoided it for so long. I always had an excuse and I was genuinely confused about how the app worked. But with no alternatives left I made a few videos “just to test out some of the filters” and I was instantly hooked.

Now, a green screen and a set of box lights are permanently installed in his Brooklyn studio so he can film whenever inspiration strikes, provided it’s not too steamy to don the tights, cowls, wigs and woolens that are an integral part of Greedy Peasant’s look.

Watch on TikTok

One of Gunther’s most eye popping creations came about when Greedy Peasant answered an ad post in the town square seeking a Spider Man (i.e., a man with spiders) to combat a bug infestation:

As a former costume design student, I’m intrigued by how superhero uniforms fit within the very conservative world of Western men’s fashion. We’re supposed to believe these color blocked bodysuits are athletic and high tech. These manly men don’t wear them just because they look great in them, they wear them for our protection and the greater good. But what if one superhero did value style over substance? Would he still retain his authoritative qualities if his super suit was embroidered and beaded and dripping with tassels? This medievalist believes so.

About that tassel obsession…

To me tassels represent ornamentation for ornamentation’s sake at its peak. This decorative concept is so maligned in our current age. 21st century design trends are so sleek and smooth, which does make our lives practical and efficient. But soon we’ll all be dead. Medieval artisans seemed to understand this on some level. I think if iPhones were sold in the middle ages they would have 4 tassels on each corner. Why? Because it would look very nice. A tassel looks beautiful as a piece of static sculpture. It adds an air of authority and polish to whatever object it is attached to. If that were all they provided us it would be enough. But then suddenly you give your elbow a little flick and before you know it your sleeve tassels are in flight! They are performing a personal ballet with their little strings going wherever the choreography may take them. It’s a gift.

Gunther’s keen eye extends to his green screen backgrounds, many of which are drawn from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s online image collection.

He also shoots on location when the situation warrants:

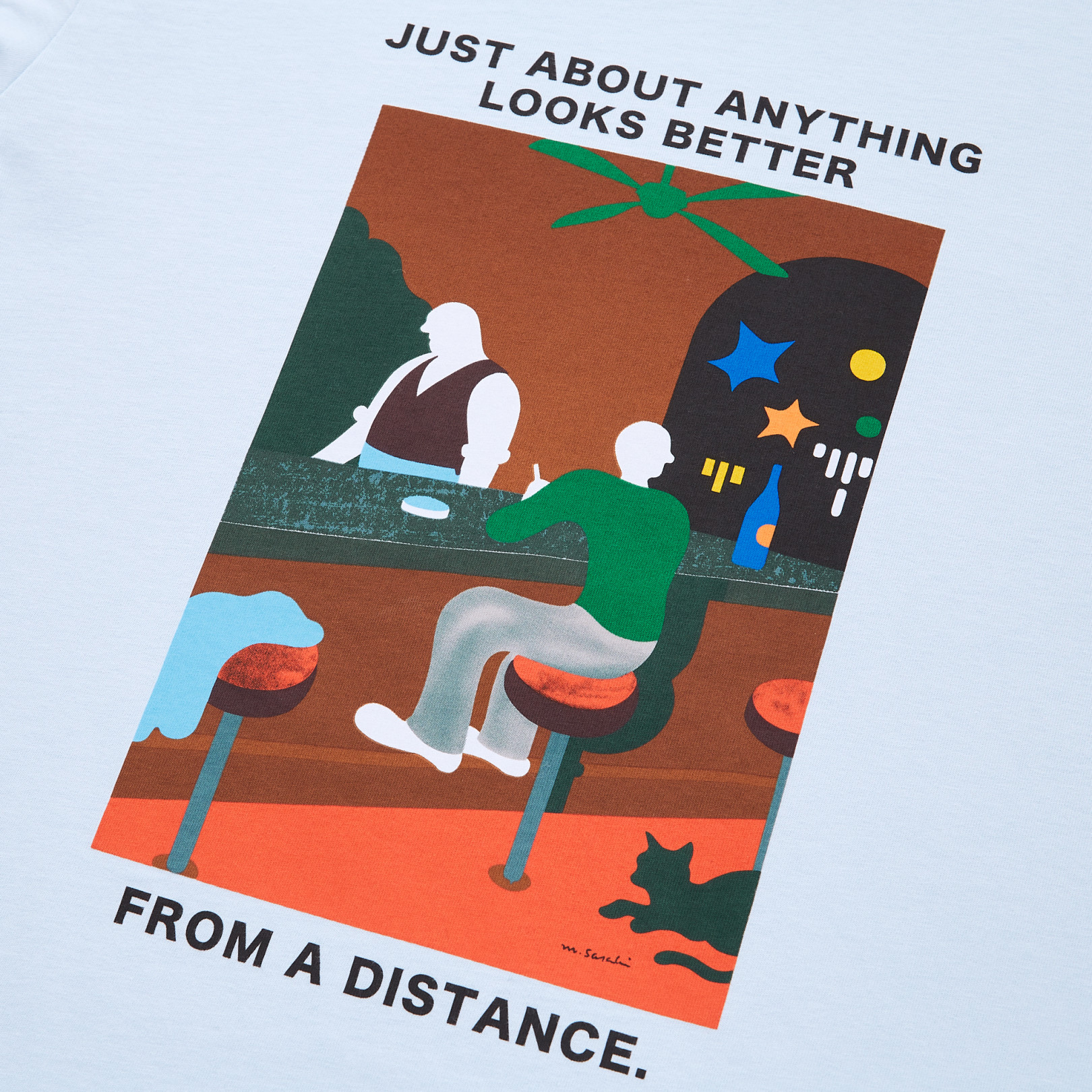

Especially in New York City, where it seems like every neighborhood has at least one building dressed up to look as if it survived the Black Plague. I love this blatantly false illusion of a heroic past. We American’s know it’s a façade. We know the building was built in 1910, not 1410, but somehow it still pleases us. Even when I went home to Arkansas to visit family, we were constantly scouting filming locations which looked convincingly medieval. Our greatest find were the back rooms and the choir loft of a beautiful gothic revival church in our town.

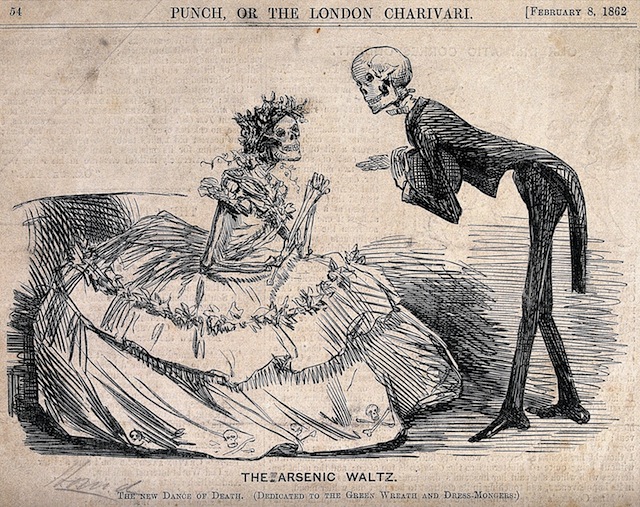

While Gunther is obviously his own star attraction, he alternates screen time with a group of “reliquary ladies,” whose main trio, Bridgette, Amanda and Susan are the queen bees of the side aisle. Even before he used a green screen filter to animate them with his eyes, lips, and a hint of mustache, he was drawn to their hairdos and individual personalities during repeat visits to the Met Cloisters.

“As reliquaries, they embody such a specific medieval sensibility,” he enthuses. “Each housed a small body part of a deceased saint, which people would make a pilgrimage to see. This combination of the sacred, macabre and beautiful includes all my favorite medieval elements.”

Watch on TikTok

Get to know Tyler Gunther’s Greedy Peasant here.

Related Content:

A Free Yale Course on Medieval History: 700 Years in 22 Lectures

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.