What is it that makes us human? And how best to ensure that we all get our fair say?

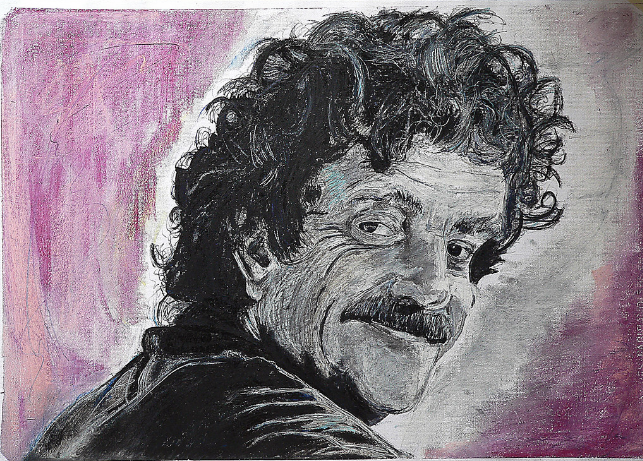

For director, photographer, and environmental activist Yann Arthus-Bertrand, the answers lay in framing all of his interview subjects using the same single image layout. The formal simplicity and unwavering gaze of his new documentary, Human, encourage viewers to perceive his 2,020 subjects as equals in the storytelling realm.

There’s a deep diversity of experiences on display here, arranged for maximum resonance.

The quietly content first wife of a polygamist marriage is followed by a polyamorous fellow, whose unconventional lifestyle is a source of both torment and joy.

There’s a death row inmate. A lady so confident she appears with her hair in curlers.

Where on earth did he find them?

His subjects hail from 60 countries. Arthus-Bertrand obviously went out of his way to be inclusive, resulting in a wide spectrum of gender and sexual orientations, and subjects with disabilities, one a Hiroshima survivor.

Tears, laughter, conflicting emotions… students of theater and psychiatry would do well to bookmark this page. There’s a lot one can glean from observing these subjects’ unguarded faces.

The project was inspired by an impromptu chat with a Malian farmer. The director was impressed by the frankness with which this stranger spoke of his life and dreams:

I dreamed of a film in which the power of words would resonate with the beauty of the world. Putting the ills of humanity at the heart of my work—poverty, war, immigration, homophobia—I made certain choices. Committed, political choices. But the men talked to me about everything: their difficulty in growing as well as their love and happiness. This richness of the human word lies at the heart of Human.

In Volume I, above, the interviewees consider love, women, work, and poverty. Volume II deals with war, forgiveness, homosexuality, family, and the afterlife. Happiness, education, disability, immigration, corruption, and the meaning of life are the concerns of the third volume .

The interview segments are broken up by aerial sequences, reminiscent of the images in Arthus-Bertrand’s book, The Earth from Above. It’s a good reminder of how small we all are in the grand scheme of things.

Appropriately, given the subject matter, and the director’s longtime interest in environmental issues, the filming and promotion were accomplished in the most sustainable way, with the support of the GoodPlanet Foundation and the United Carbon Action program. It would be lovely for all humanity if this is a feature of filmmaking going forward.

The Google Cultural Institute has a collection of related material, from the making of the soundtrack to behind-the-scenes reminiscences of the interview team.

Human will be added to our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

What Makes Us Human?: Chomsky, Locke & Marx Introduced by New Animated Videos from the BBC

Richard Dawkins Explains Why There Was Never a First Human Being

Biology That Makes Us Tick: Free Stanford Course by Robert Sapolsky

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Her new play, Fawnbook, opens in New York City later this fall. Follow her @AyunHalliday.