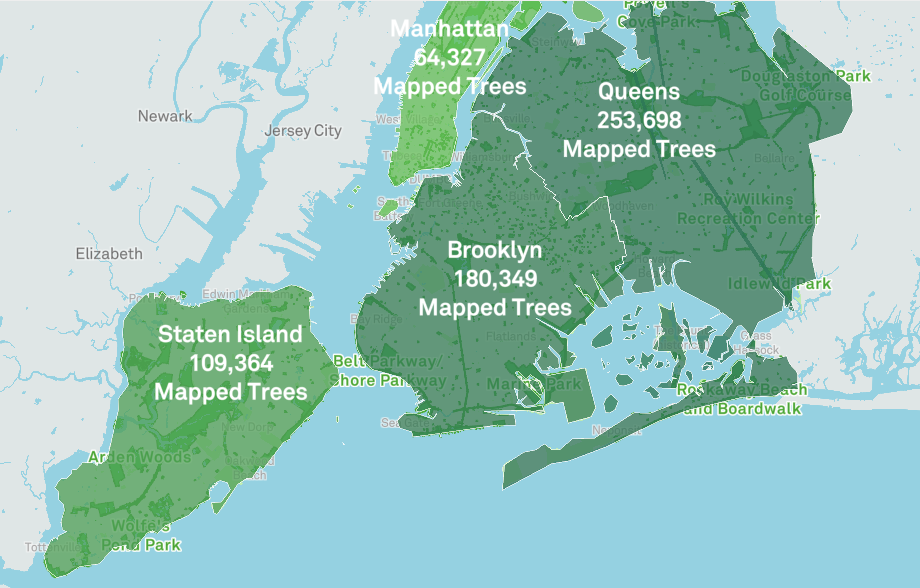

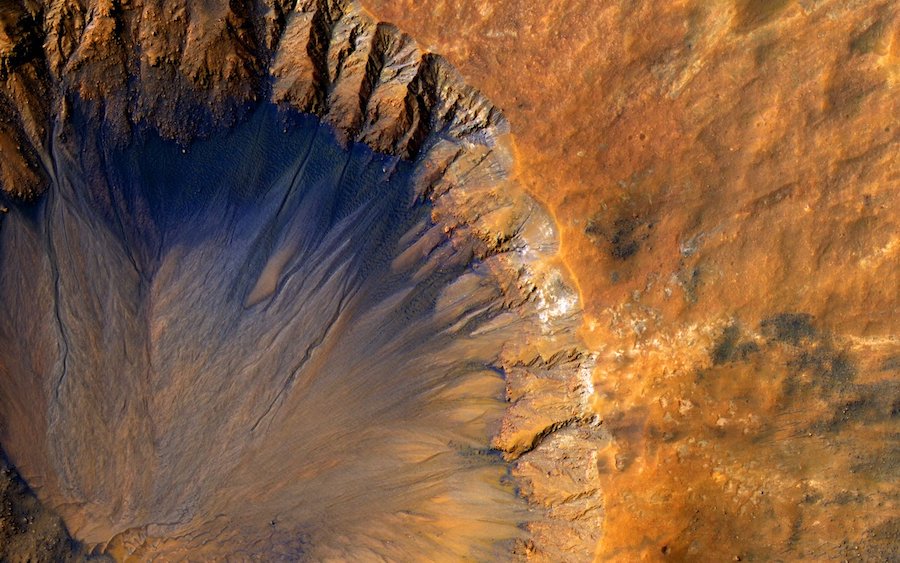

If you keep up with climate change news, you see a lot of predictions of what the world will look like twenty years from now, fifty years from now, a century from now. Some of these projections of the state of the land, the shape of continents, and the levels of the sea are more dramatic than others, and in any case they vary so much that one never knows which ones to credit. But of equal importance to foreseeing what Earth will look like in the future is not forgetting what it looks like now — or so holds the premise of the Earth Archive, a scientific effort to “scan the entire surface of the Earth before it’s too late.”

This ambitious project has three goals: to “create a baseline record of the earth as it is today to more effectively mitigate the climate crisis,” to “build a virtual, open-source planet accessible to all scientists so we can better understand our world,” and to “preserve a record of the Earth for our grandchildren’s grandchildren so they can study & recreate our lost heritage.”

All three depend on the creation of a detailed 3D model of the globe — but “globe” is the wrong word, bringing to mind as it does a sphere covered with flat images of land and sea.

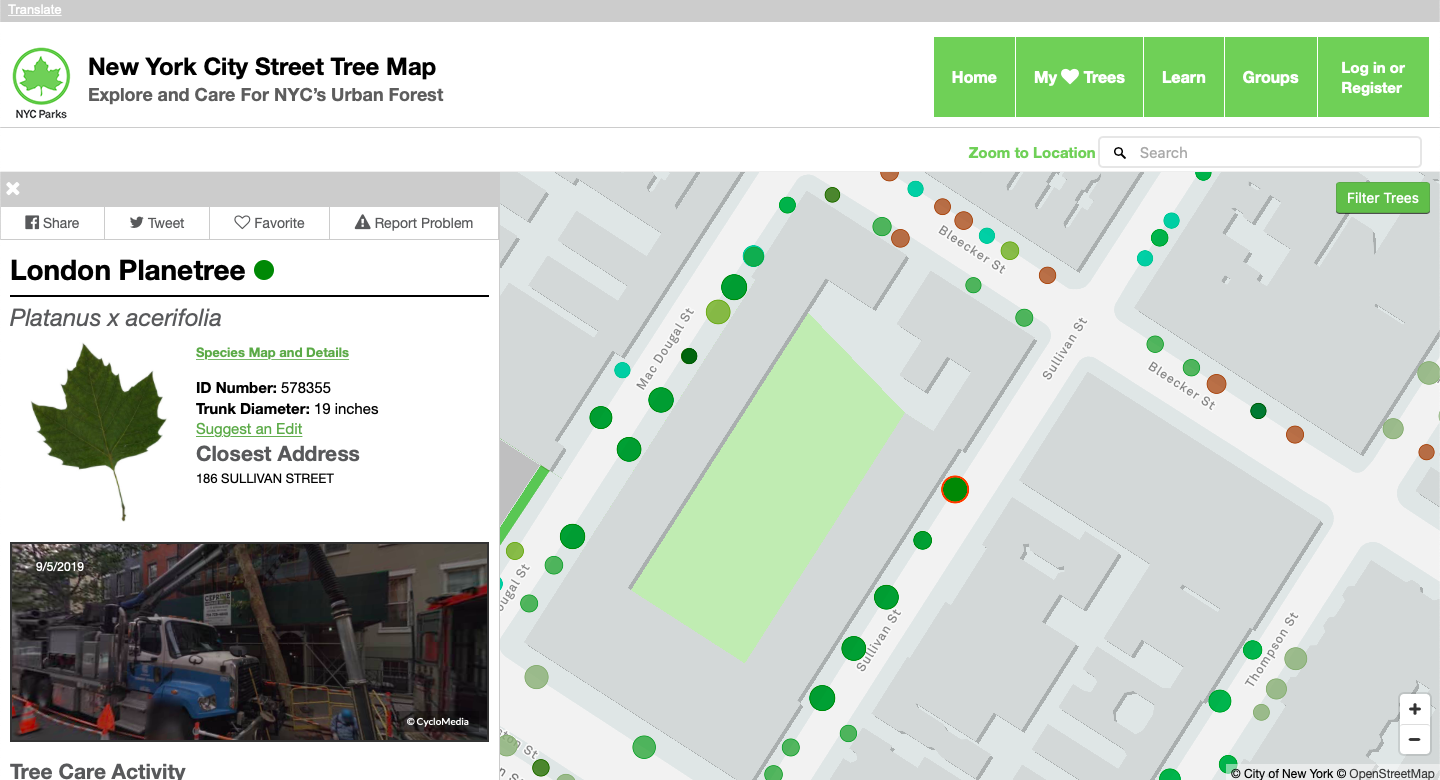

Using lidar (short for Light Detection & Ranging), a technology that “involves shooting a dense grid of infrared beams from an airplane towards the ground,” the Earth Archive aims to create not an image but “a dense three-dimensional cloud of points” capturing the whole planet. At the top of the post, you can see a TED Talk on the Earth Archive’s origin, purpose, and potential by archaeologist and anthropology professor Chris Fisher, the project’s founder and director. “Fisher had used lidar to survey the ancient Purépecha settlement of Angamuco, in Mexico’s Michoacán state,” writes Atlas Obscura’s Isaac Schultz. “In the course of that work, he saw human-caused changes to the landscape, and decided to broaden his scope.”

Now, Fisher and Earth Archive co-director Steve Leisz want to create “a comprehensive archive of lidar scans” to “fuel an immense dataset of the Earth’s surface, in three dimensions.” This comes with certain obstacles, not the least the price tag: a scan of the Amazon rainforest would take six years and cost $15 million. “The next step,” writes Schultz, “could be to use some future technology that puts lidar in orbit and makes covering large areas easier.” Disinclined to wait around for the development of such a technology while forests burn and coastlines erode, Fisher and Leisz are taking their first steps — and taking donations — right now. On the off chance that humans of centuries ahead develop the ability to recreate the planet as we know it today, it’s the Earth Archive’s data they’ll rely on to do it.

via Atlas Obscura

Related Content:

A Century of Global Warming Visualized in a 35 Second Video

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.