When you picture modern day Tokyo, what comes to mind?

The electronic billboards of Shibuya and Shinjuku?

The teeming streets?

The maid cafes?

The robot hotel?

A 97 square foot micro apartment?

Bernard Guerrini’s documentary Naturopolis — Tokyo, from megalopolis to garden-city describes Tokyo as “a giant city, a city which never stops growing:”

It has destroyed its natural spaces. It has created its own weather. It’s too big for its own good. They say Tokyo is like an amoeba that absorbs everything in its path.

It’s a far cry from the urban space Tokugawa Ieyasu, founder of the Tokugawa Shogunate, intended when planting the seeds for Edo, as Tokyo was originally called.

As the above excerpt from Naturopolis explains, the 16th-century city was innovative in its incorporation of green space.

The daimyō, or military lords, were required by the shogunate to keep residences in Edo. Each of these homes was furnished with a gardener and a landscaper to maintain the beauty of its al fresco areas.

Meanwhile, crops were cultivated in all communal outdoor open spaces, with irrigation canals supplying the necessary water for growing rice.

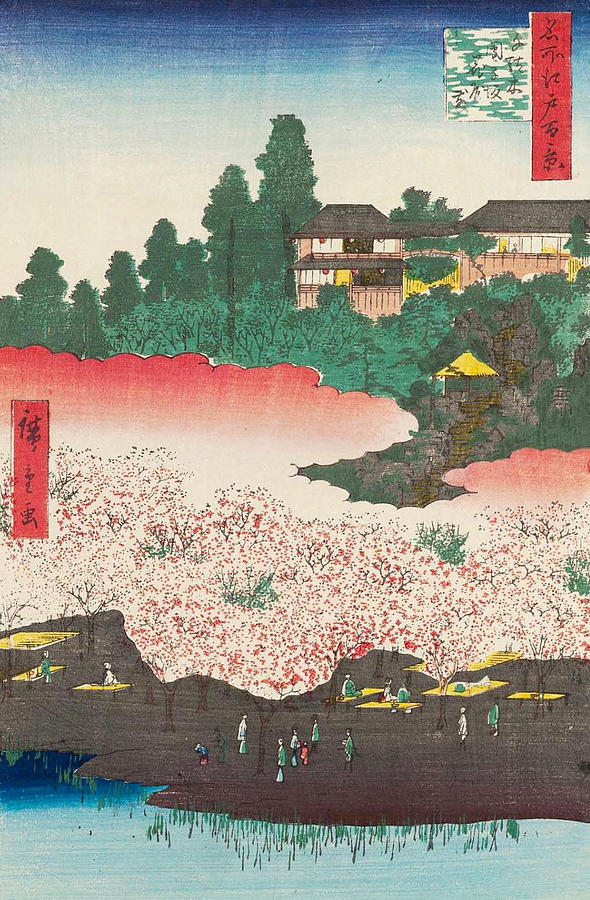

These plant-rich settings provided a hospitable environment for animals both wild and domestic. The carefully curated natural zones invited quiet contemplation of flora and fauna, giving rise to the seasonal celebrations and rites that are still observed throughout Japan.

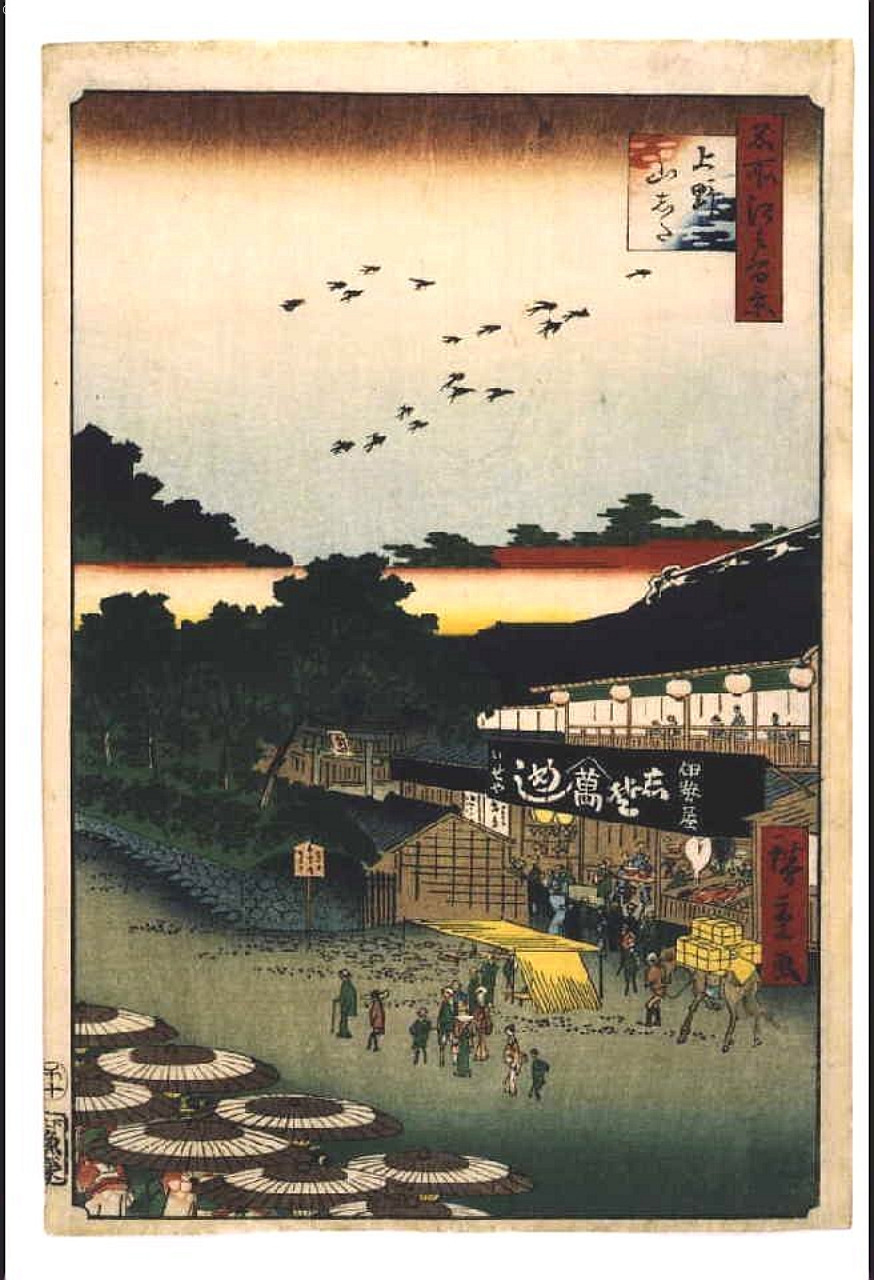

Whether admiring blossoms and fireflies in spring and summer or autumn leaves and snowy winter scenes in the colder months, Edo’s citizens revered the natural world outside their doorsteps.

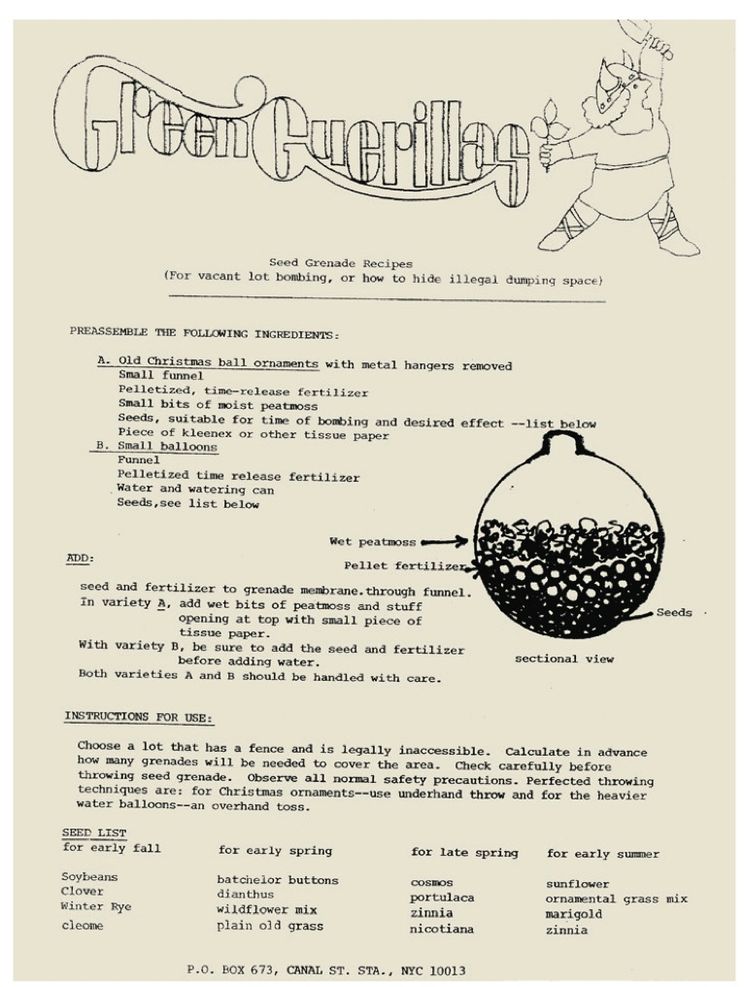

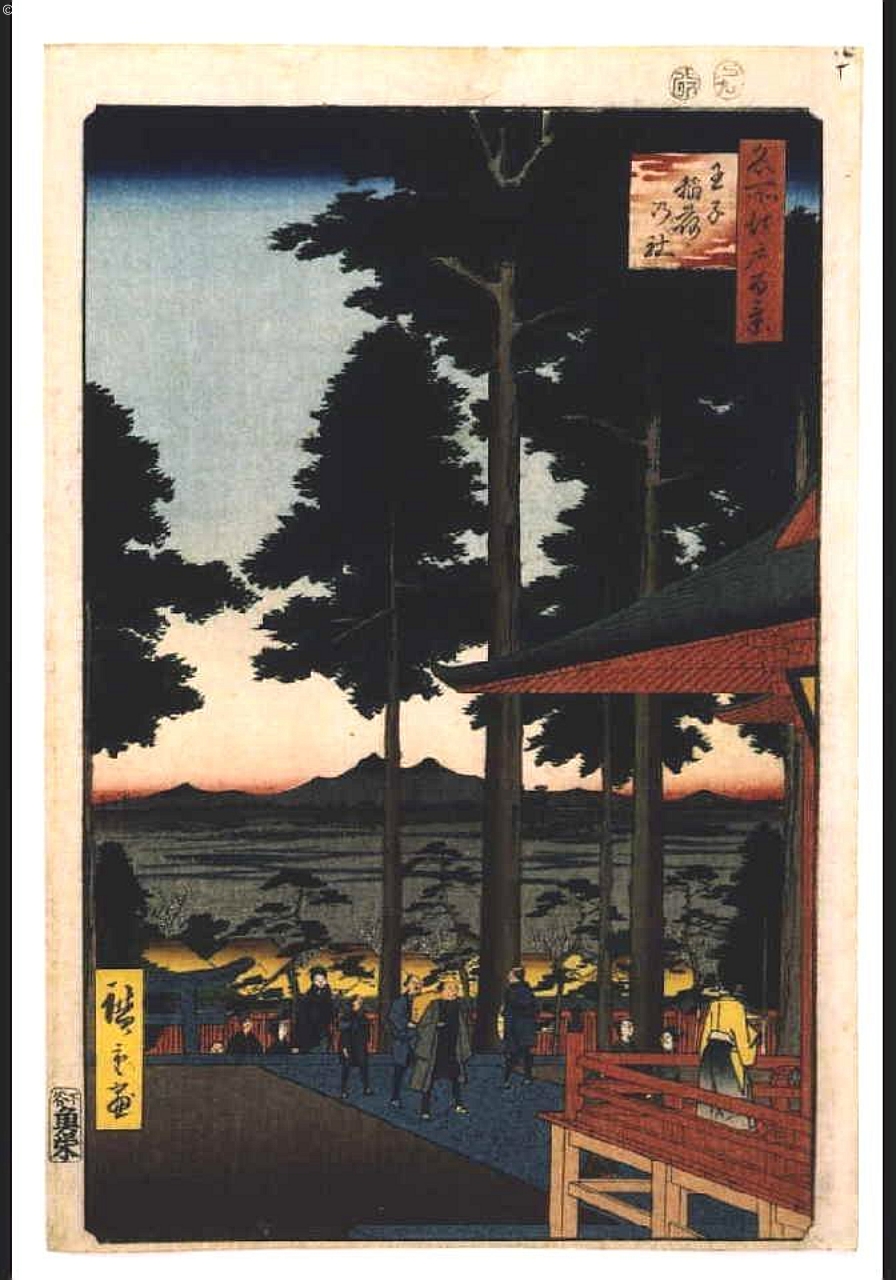

Bashō did the same in his haiku; Utagawa Hiroshige in his series of ukiyo‑e prints, One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.

Somewhat less poetically celebrated was the importance of night soil to this biodynamic, pre-industrial shogunate capital. As environmental writer Eisuke Ishikawa delicately notes in Japan in the Edo Period — An Ecologically-Conscious Society:

A long time ago, when excrement was a precious fertilizer, it naturally belonged to the person who produced it. Farmers used to buy excrement for cash or trade it for a comparable amount of vegetables. Fertilizer shortages were a chronic problem during the Edo period. As the standard of living in cities improved, surrounding villages needed an increasing amount of fertilizer…

(Anyone who’s shouldered the surprisingly heavy interactive–not THAT interactive–night soil buckets on display in Tokyo’s Edo Museum will have a feel for just how much of this necessary element each block of the capital city generated on a daily basis.)

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 brought many changes — a new government, a new name for Edo, and a race toward Western-style industrialization. Many parks and gardens were destroyed as Tokyo rapidly expanded beyond Edo’s original footprint.

But now, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government is looking to its past in an effort to combat the effects of climate change with a push toward environmental sustainability.

The goal is net zero CO2 emissions by 2050, with 2030 serving as a benchmark.

In addition to holding the business, financial, and energy sectors to environmentally responsible standard, the zero emission plan seeks to address the average citizen’s quality of life, with a literal return to more green spaces:

Accelerating climate change measures is important to preserve biodiversity and continue to reap its bounty. In recent years, the idea of green infrastructure that utilizes the functions of the natural environment has attracted attention. It is one of the most important considerations for the future: achieving both biodiversity conservation and climate change measures.

A United Nation report* pointed out that COVID-19 is potentially a zoonotic disease derived from wildlife, such infectious diseases will increase in the future, and one of the reasons is the destruction of nature by humans.

Read Tokyo Metropolitan Government’s Zero Transmission Strategy and Update here.

Related Content

Wabi-Sabi: A Short Film on the Beauty of Traditional Japan

See How Traditional Japanese Carpenters Can Build a Whole Building Using No Nails or Screws

The Entire History of Japan in 9 Quirky Minutes

Cats in Japanese Woodblock Prints: How Japan’s Favorite Animals Came to Star in Its Popular Art

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.