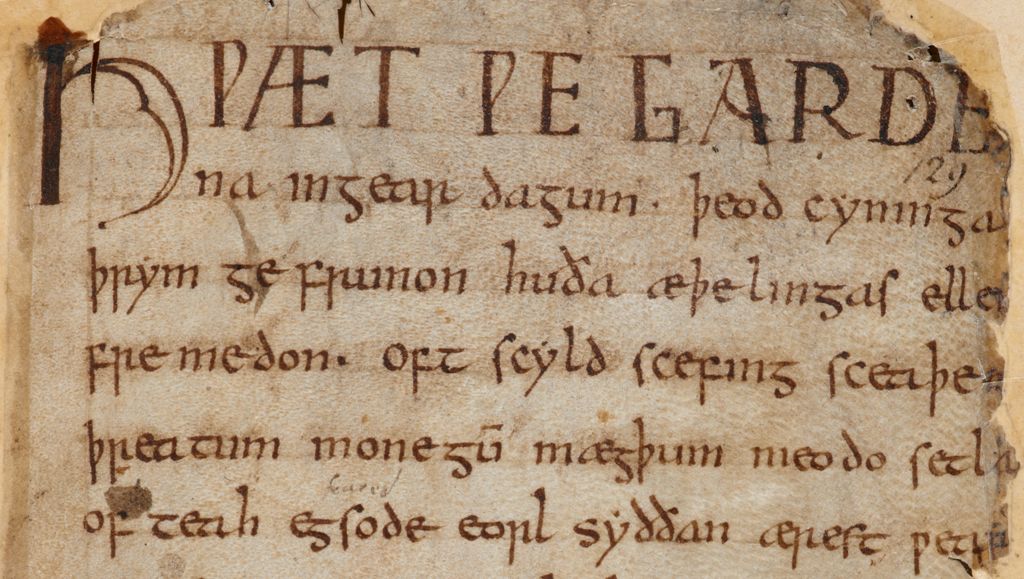

I was as surprised as most people are when I first heard the ancient language known as Old English. It’s nothing like Shakespeare, nor even Chaucer, who wrote in a late Middle English that sounds strange enough to modern ears. Old English, the English of Beowulf, is almost a foreign tongue; close kin to German, with Latin, Norse, and Celtic influence.

As you can hear in the Beowulf reading above from The Telegraph, it’s a thick, consonant-rich language that may put you in mind of J.R.R. Tolkien’s elvish. The language arrived in Briton—previously inhabited by Celtic speakers—sometime in the fifth century, though whether the Anglo-Saxon invasion was a hostile takeover by Germanic mercenaries or a slow population drift that introduced a new ethnicity is a matter of some dispute. Nevertheless it’s obvious from the reading above—and from texts in the language like this online edition of Beowulf in its original tongue—that we would no more be able to speak to the Anglo-Saxons than we would to the Picts and Scots they conquered.

So how is it that both the language we speak and its distant ancestor can both be called “English”? Well, that is what its speakers called it. As the author of this excellent Old English introductory textbook writes, speakers of “Old English,” “Middle English,” and “Modern English” are “themselves modern”; They “would have said, if asked, that the language they spoke was English.” The changes in the language “took place gradually, over the centuries, and there never was a time when people perceived their language as having broken radically with the language spoken a generation before.” And while “relatively few Modern English words come from Old English […] the words that do survive are some of the most common in the language, including almost all the ‘grammar words’ (articles, pronouns, prepositions) and a great many words for everyday concepts.” You may notice a few of those distant linguistic ancestors in the Beowulf passage accompanying the reading above.

Beowulf is, of course, the oldest epic poem in English, written sometime between the 8th and early 11th century. It draws, however, not from British sources but from Danish myth, and is in fact set in Scandinavia. The title character, a hero of the Geats—or ancient Swedes—travels to Denmark to offer his services to the king and defeat the monster Grendel (and his mother). The product of a warrior culture, the poem shares much in common with the epics of Homer with its code of honor and praise of fighting prowess. And here see vocalist, harpist, and medieval scholar Benjamin Bagby perform the opening lines of the poem as its contemporary audience would have experienced it—intoned by a bard with an Anglo-Saxon harp. The modern English subtitles are a boon, but close your eyes for a moment and just listen to the speech—see if you can pick out any words you recognize. Then, perhaps, you may wish to turn to Fordham University’s online translation and find out what all that big talk in the prologue is about.

And for a very short course on the history of English, see this concise page and this ten-minute animated video from Open University.

The image above comes from the sole surviving medieval manuscript of Beowulf, which now resides at the British Library.

Related Content:

Hear Homer’s Iliad Read in the Original Ancient Greek

What Ancient Greek Music Sounded Like: Hear a Reconstruction That is ‘100% Accurate’

Seamus Heaney Reads His Exquisite Translation of Beowulf

Hear The Epic of Gilgamesh Read in the Original Akkadian, the Language of Mesopotamia

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness