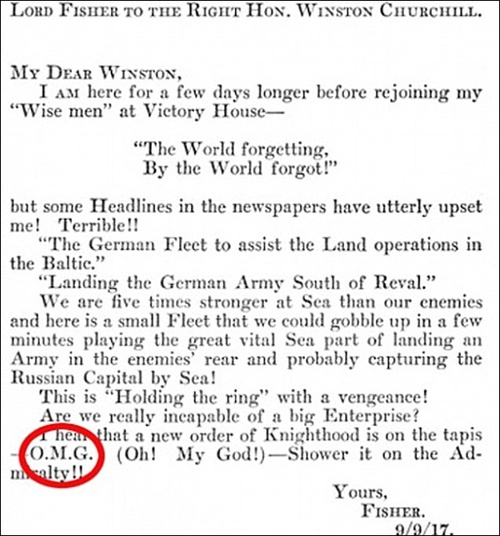

We live in an age of mash ups. A few years ago some malcontent came up with Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. Our cities are teeming with food trucks hawking Korean tacos and ramen burgers. And chess boxing is apparently a thing. So perhaps it isn’t surprising that some evil genius would merge the most quotable movie of the past 20 years, The Big Lebowski, with William Shakespeare.

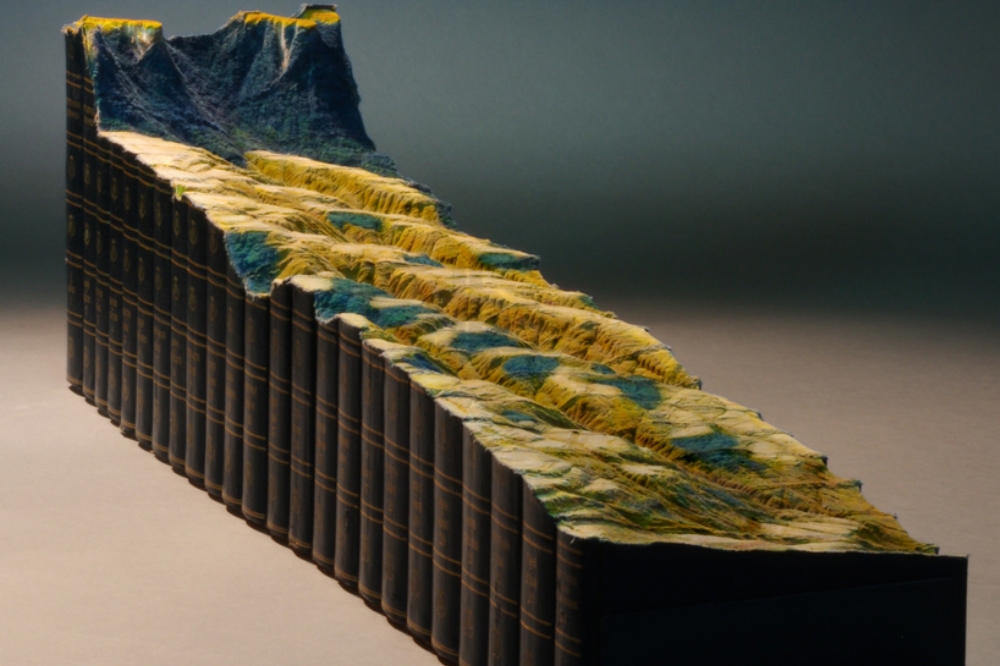

The resulting book, written by Adam Bertocci, is called Two Gentlemen of Lebowski, and it does a surprisingly good job of capturing the language of the Bard while staying true to the original movie. The author reportedly wrote the first draft of the book in a single sleepless weekend. An impressive feat that the author dismisses in an interview with CNN that you can see above.

“Anybody could, given the lack of a social life,” deadpans Bertocci, “take a weekend with a movie they admired and an author that they knew well and make a similarly lengthy mash up of it.”

In Bertocci’s fevered reworking (read the first 3 scenes for free here), the Dude is recast as The Knave. His belligerent best friend is Sir Walter of Poland. The hapless Donnie is Sir Donald of Greece. Knox Harrington, Mauve’s gratingly giggly conceptual artist friend, is in this version a tapestry artist. And of course, Da Fino, the PI, who shadows the Dude in the movie, is listed simply as Brother Seamus.

But where Bertocci really shines is in his clever appropriation of Shakespearean language. The film’s copious profanity has been replaced with more Bard-worthy epithets like “rash egg” or “varlet.” The word “verily” peppers the Knave’s dialogue as the word “like” peppers the Dude’s. And when Walter waxes poetic about the rules of bowling, he does so in iambic pentameter.

To get a sense of the differences, compare the clip above from the movie with the Bard-ofied text of the same scene below.

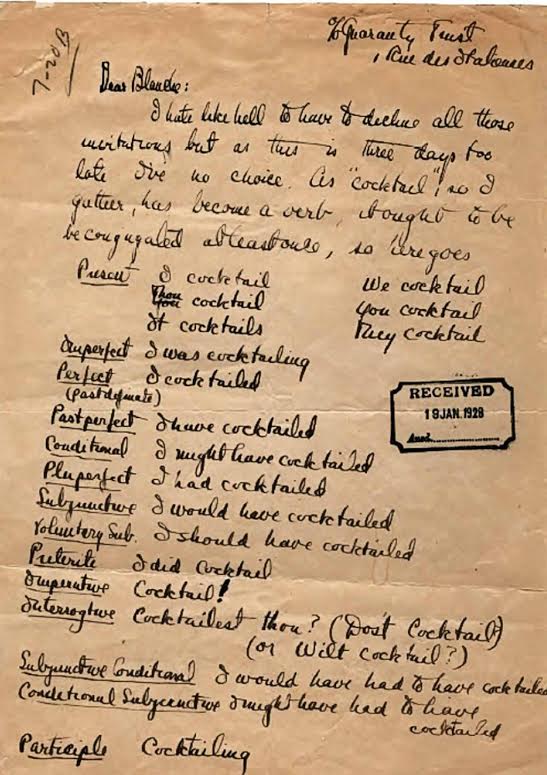

THE KNAVE’s house. Enter THE KNAVE, carrying parcels, and BLANCHE and WOO. They fight.

BLANCHE

Whither the money, Lebowski? Faith, we are as servants to Bonnie;

promised by the lady good that thou in turn were good for’t.WOO

Bound in honour, we must have our bond; cursed be our tribe

if we forgive thee.BLANCHE

Let us soak him in the chamber-pot, so as to turn his head.WOO

Aye, and see what vapourises; then he will see what is foul.They insert his head into the chamber-pot.

BLANCHE

What dreadful noise of waters in thine ears! Thou hast cool’d

thy head; think now upon drier matters.WOO

Speak now on ducats else again we’ll thee duckest; whither the

money, Lebowski?THE KNAVE

Faith, it awaits down there someplace; prithee let me glimpse

again.WOO

What, thou rash egg! Thus will we drown thine exclamations.They again insert his head into the chamber-pot.

BLANCHE

Trifle not with the fury of two desperate men. Long has thy

wife sealed a bond with Jaques Treehorn; as blood is to blood,

surely thou owest to Jaques Treehorn in recompense.WOO

Rise, and speak wisely, man—but hark;

I see thy rug, as woven i’the Orient,

A treasure from abroad. I like it not.

I’ll stain it thus; to deadbeats ever thus.He stains the rug.

THE KNAVE

Sir, prithee nay!BLANCHE

Now thou seest what happens, Lebowski, when the agreements

of honourable business stand compromised. If thou wouldst

treat money as water, flowing as the gentle rain from heaven,

why, then thou knowest water begets water; it will be a watery

grave your rug, drown’d in the weeping brook. Pray remember,

Lebowski.THE KNAVE

Thou err’st; no man calls me Lebowski. Hear rightly, man!—for

thou hast got the wrong man. I am the Knave, man; Knave in

nature as in name.BLANCHE

Thy name is Lebowski. Thy wife is Bonnie.THE KNAVE

Zounds, man. Look at these unworthiest hands; no gaudy gold

profanes my little hand. I have no honour to contain the ring. I

am a bachelor in a wilderness. Behold this place; are these the

towers where one may glimpse Geoffrey, the married man? Is

this a court where mistresses of common sense are hid? Not for

me to hang my bugle in an invisible baldric, sir; I am loath to

take a wife, or she to take me until men be made of some other

mettle than earth. Hark, the lid of my chamber-pot be lifted!

Personally, I’m hoping that the Globe Theatre stages a version of this.

While you are waiting for that to happen, you can see another scene from Two Gentlemen from Lebowski above where The Knave and Sir Walter commiserate about a rug, which was besmirched by a “most miserable tide.”

Related Content:

The Big Lebowski Reimagined as a Classic 8‑Bit Video Game

Watch the Coen Brothers’ TV Commercials: Swiss Cigarettes, Gap Jeans, Taxes & Clean Coal

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.