Philosophers have always distrusted language for its slipperiness, its overuse, its propensity to deceive. Yet many of those same critics have devised the most inventive terms to describe things no one had ever seen. The Philosopher’s Stone, the aether, miasmas—images that made the ineffable concrete, if still invisibly gaseous.

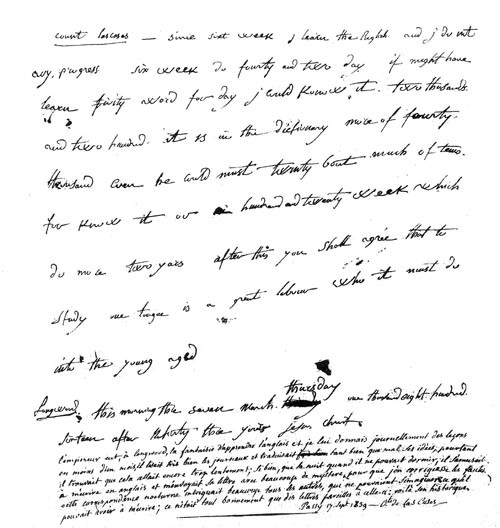

It’s important for us to see the myriad ways our common language fails to capture the complexity of reality, ordinary and otherwise. Ask any poet, writer, or language teacher to tell you about it—most of the words we use are too abstract, too worn out, decayed, or rusty. Maybe it takes either a poet or a philosopher to not only notice the many problems with language, but to set about remedying them.

Such are the qualities of the mind behind The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows, a project by graphic designer and filmmaker John Koenig. The blog, YouTube channel, and soon-to-be book from Simon & Schuster has a simple premise: it identifies emotional states without names, and offers both a poetic term and a philosopher’s skill at precise definition. Whether these words actually enter the language almost seems beside the point, but so many of them seem badly needed, and perfectly crafted for their purpose.

Take one of the most popular of these, the invented word “Sonder,” which describes the sudden realization that everyone has a story, that “each random passerby is living a life as vivid and complex as your own.” This shock can seem to enlarge or diminish us, or both at the same time. Psychologists may have a term for it, but ordinary speech seemed lacking.

Sonder likely became as popular as it did on social media because the theme “we’re all living connected stories” already resonates with so much popular culture. Many of the Dictionary’s other terms trend far more unambiguously melancholy, if not neurotic—hence “obscure sorrows.” But they also range considerably in tone, from the relative lightness of Greek-ish neologism “Anecdoche”—“a conversation in which everyone is talking, but nobody is listening”—to the majorly depressive “pâro”:

the feeling that no matter what you do is always somehow wrong—as if there’s some obvious way forward that everybody else can see but you, each of them leaning back in their chair and calling out helpfully, “colder, colder, colder…”

Both the coinages and the definitions illuminate each other. Take “Énouement,” defined as “the bittersweetness of having arrived in the future, seeing how things turn out, but not being able to tell your past self.” A psychology of aging in the form of an eloquent dictionary entry. Sometimes the relationship is less subtle, but still magical, as in the far from sorrowful “Chrysalism: The amniotic tranquility of being indoors during a thunderstorm.”

Sometimes, it is not a word but a phrase that speaks most poignantly of emotions that we know exist but cannot capture without deadening clichés. “Moment of Tangency” speaks poignantly of a metaphysical philosophy in verse. Like Sonder, this phrase draws on an image of interconnectedness. But rather than taking a perspective from within—from solipsism to empathy—it takes the point of view of all possible realities.

Watch the video for “Vemödalen: The Fear That Everything Has Already Been Done” up top. See several more short films from the project here, including “Silience: The Brilliant Artistry Hidden All Around You”—if, that is, we could only pay attention to it. Below, find 23 other entries describing emotions people feel, but can’t explain.

1. Sonder: The realization that each passerby has a life as vivid and complex as your own.

2. Opia: The ambiguous intensity of Looking someone in the eye, which can feel simultaneously invasive and vulnerable.

3. Monachopsis: The subtle but persistent feeling of being out of place.

4 Énouement: The bittersweetness of having arrived in the future, seeing how things turn out, but not being able to tell your past self.

5. Vellichor: The strange wistfulness of used bookshops.

6. Rubatosis: The unsettling awareness of your own heartbeat.

7. Kenopsia: The eerie, forlorn atmosphere of a place that is usually bustling with people but is now abandoned and quiet.

8. Mauerbauertraurigkeit: The inexplicable urge to push people away, even close friends who you really like.

9. Jouska: A hypothetical conversation that you compulsively play out in your head.

10. Chrysalism: The amniotic tranquility of being indoors during a thunderstorm.

11. Vemödalen: The frustration of photographic something amazing when thousands of identical photos already exist.

12. Anecdoche: A conversation in which everyone is talking, but nobody is listening

13. Ellipsism: A sadness that you’ll never be able to know how history will turn out.

14. Kuebiko: A state of exhaustion inspired by acts of senseless violence.

15. Lachesism: The desire to be struck by disaster – to survive a plane crash, or to lose everything in a fire.

16. Exulansis: The tendency to give up trying to talk about an experience because people are unable to relate to it.

17. Adronitis: Frustration with how long it takes to get to know someone.

18. Rückkehrunruhe: The feeling of returning home after an immersive trip only to find it fading rapidly from your awareness.

19. Nodus Tollens: The realization that the plot of your life doesn’t make sense to you anymore.

20. Onism: The frustration of being stuck in just one body, that inhabits only one place at a time.

21. Liberosis: The desire to care less about things.

22. Altschmerz: Weariness with the same old issues that you’ve always had – the same boring flaws and anxieties that you’ve been gnawing on for years.

23. Occhiolism: The awareness of the smallness of your perspective.

Related Content:

“Tsundoku,” the Japanese Word for the New Books That Pile Up on Our Shelves, Should Enter the English Language

The Largest Historical Dictionary of English Slang Now Free Online: Covers 500 Years of the “Vulgar Tongue”

How a Word Enters the Dictionary: A Quick Primer

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him at @jdmagness