Among the political and social revolutions of the 1960s, the movement to democratize education is of central historical importance. Parents and politicians were entrenched in battles over integrating local schools years after 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education. Sit-ins and protests on college campuses made similar student unrest today seem mild by comparison. Meanwhile, quieter, though no less radical, educational movements proliferated in communes, homeschools, and communities that could pay for private schools.

Most of these experimental methods drew from older sources, such as the theories of Rudolf Steiner and Maria Montessori, both of whom died before the Age of Aquarius. One movement that got its start decades earlier was popularized in the 60s when its founder A.S. Neill published the influential Summerhill: A Radical Approach to Child Rearing, a classic work of alternative pedagogy in which the Scottish writer and educator described the radical ideas developed in his Summerhill School in England, first founded in 1921.

Neill’s school “helped to pioneer the ‘free school’ philosophy,” writes Aeon, “in which lessons are never mandatory and nearly every aspect of student life can be put to a vote.” His methods “and a rising countercultural movement inspired similar institutions to open around the world.” When Neill first published his book, however, he was very much on the defensive, against “an increasing reaction against progressive education,” psychologist Erich Fromm wrote in the book’s foreword.

At the extreme end of this backlash Fromm situates “the remarkable success in teaching achieved in the Soviet Union,” where “the old-fashioned methods of authoritarianism are applied in full strength.” Fromm defended experiments like Neill’s, despite their “often disappointing” results, as a natural outgrowth of the Enlightenment.

During the eighteenth century, the ideas of freedom, democracy, and self-determination were proclaimed by progressive thinkers; and by the first half of the 1900’s these ideas came to fruition in the field of education. The basic principle of such self-determination was the replacement of authority by freedom, to teach the child without the use of force by appealing to his curiosity and spontaneous needs, and thus to get him interested in the world around him. This attitude marked the beginning of progressive education and was an important step in human development.

What seemed anarchic to its detractors had its roots in the tradition of individual liberty against feudal traditions of unquestioned authority. But Neill was less like John Locke, who included children in his category of irrational beings (along with “idiots” and “Indians”) than he was like Jean Jacques Rousseau. Fromm suggests this too: “A.S. Neill’s system is a radical approach to child rearing because it represents the true principle of education without fear. In Summerhill School authority does not mask a system of manipulation.”

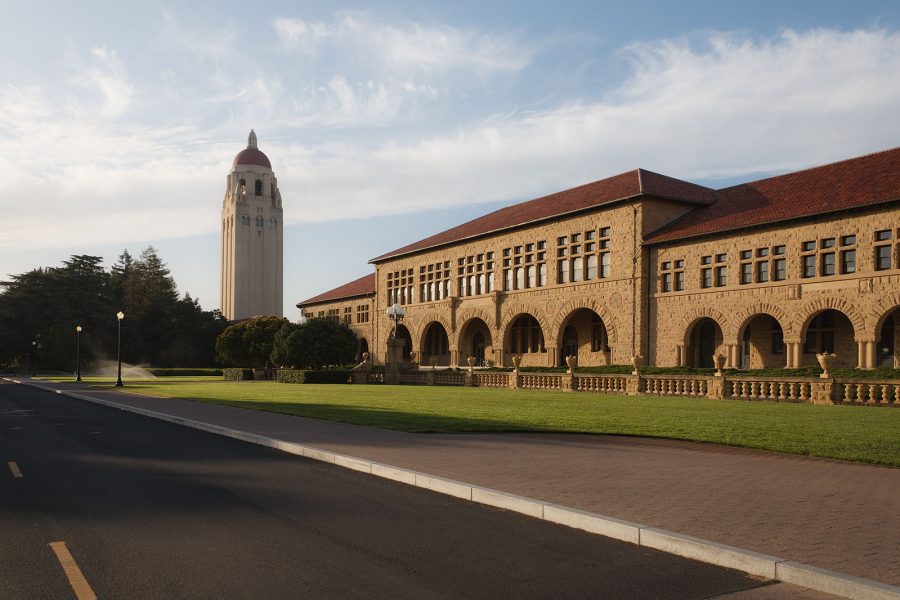

Students decide what they want to learn, and what they don’t, with no curriculum, requirements, or testing to speak of and no structured time or mandatory attendance. Is such a thing even possible in practice? How could educators manage and measure student progress, or ensure their students learn anything at all? What might this look like? Find out in the 1966 National Film Board of Canada documentary Summerhill, above, full of “candid moments and scenes,” Aeon writes, “that evoke the rhythms of daily life at the school and give a sense of the children’s lived experience.”

Disorganized, but not chaotic, classroom bustle contrasts with idyllic, sunlit moments on Summerhill’s verdant grounds and honest criticism, some from the students themselves. One girl admits that the free play wears thin after a while and that “there probably aren’t such good facilities for learning here, after a certain level. But you can always go somewhere else afterwards” (though many would have difficulty with entrance exams). Another student talks about the struggle to study without structure to help minimize distractions. Despite Neill’s philosophical aversion to fear, she says “you’re always afraid of missing something.”

We also meet the man himself, A.S. Neill, a rumpled, avuncular figure at 83 years old, who proclaims freedom as the answer for students who struggle in school, and for students who don’t. If we’re honest, we might all admit we felt this strongly as children ourselves. It may never be an impulse that’s compatible with contemporary goals for education, which is often geared toward workplace training at the expense of creative thinking. But for many students, the opportunity to pursue their own course on their own terms can become the impetus for a lifetime of independent thought and action. I can’t think of a loftier educational goal.

via Aeon

Related Content:

Noam Chomsky Spells Out the Purpose of Education

Noam Chomsky Defines What It Means to Be a Truly Educated Person

Lynda Barry on How the Smartphone Is Endangering Three Ingredients of Creativity: Loneliness, Uncertainty & Boredom

Buckminster Fuller Rails Against the “Nonsense of Earning a Living”: Why Work Useless Jobs When Technology & Automation Can Let Us Live More Meaningful Lives

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness