Open access publishing has, indeed, made academic research more accessible, but in “the move from physical academic journals to digitally-accessible papers,” Samantha Cole writes at Vice, it has also become “more precarious to preserve…. If an institution stops paying for web hosting or changes servers, the research within could disappear.” At least a couple hundred open access journals vanished in this way between 2000 and 2019, a new study published on arxiv found. Another 900 journals are in danger of meeting the same fate.

The journals in peril include scholarship in the humanities and sciences, though many publications may only be of interest to historians, given the speed at which scientific research tends to move. In any case, “there shouldn’t really be any decay or loss in scientific publications, particularly those that have been open on the web,” says study co-author Mikael Laasko, information scientist at the Hanken School of Economics in Helsinki. Yet, in digital publishing, there are no printed copies in university libraries, catalogued and maintained by librarians.

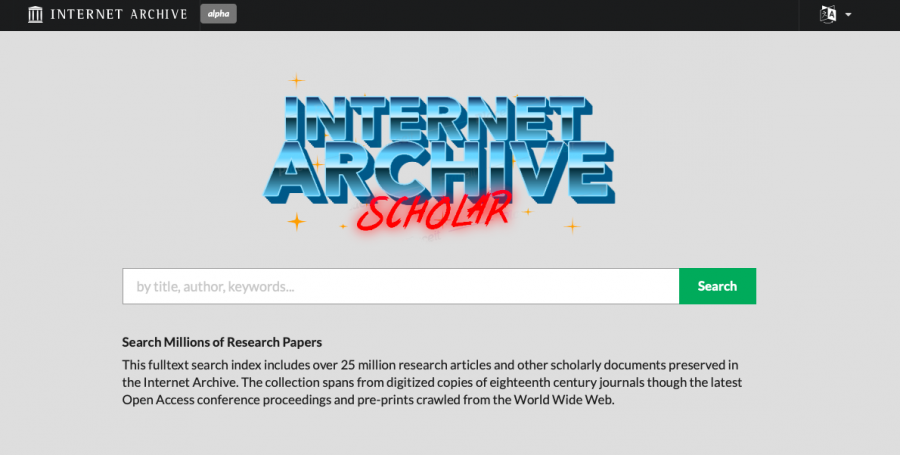

To fill the need, the Internet Archive has created its own scholarly search platform, a “fulltext search index” that includes “over 25 million research articles and other scholarly documents” preserved on its servers. These collections span digitized and original digital articles published from the 18th century to “the latest Open Access conference proceedings and pre-prints crawled from the World Wide Web.” Content in this search index comes in one of three forms:

- public web content in the Wayback Machine web archives (web.archive.org), either identified from historic collecting, crawled specifically to ensure long-term access to scholarly materials, or crawled at the direction of Archive-It partners

- digitized print material from paper and microform collections purchased and scanned by Internet Archive or its partners

- general materials on the archive.org collections, including content from partner organizations, uploads from the general public, and mirrors of other projects

The project is still in “alpha” and “has several bugs,” the site cautions, but it could, when it’s fully up and running, become part of a much-needed revolution in academic research—that is if the major academic publishers don’t find some legal pretext to shut it down.

Academic publishing boasts one of the most rapacious legal business models on the global market, and one of the most exploitative: a double standard in which scholars freely publish and review research for the public benefit (ostensibly) and very often on the public dime; while private intermediaries rake in astronomical sums for themselves with paywalls. The open access model has changed things, but the only way to truly serve the “best interests of researchers and the public,” neuroscientist Shaun Khoo argues, is through public infrastructure and fully non-profit publication.

Maybe Internet Archive Scholar can go some way toward bridging the gap, as a publicly accessible, non-profit search engine, digital catalogue, and library for research that is worth preserving, reading, and building upon even if it doesn’t generate shareholder revenue. For a deeper dive into how the Archive built its formidable, still developing, new database, see the video presentation above from Jefferson Bailey, Director of Web Archiving & Data Services. And have a look at Internet Archive Scholar here. It currently lacks advanced search functions, but plug in any search term and prepare to be amazed by the incredible volume of archived full text articles you turn up.

Related Content:

The Boston Public Library Will Digitize & Put Online 200,000+ Vintage Records

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness