British character actor Bob Hoskins has been remembered for “playing Americans better than Americans,” as USA Today wrote when Hoskins passed away in 2014. Characters like Who Framed Roger Rabbit?’s Eddie Valiant, Nixon’s J. Edgar Hoover, and The Cotton Club’s Owney Madden stand out as some of his best performances in Hollywood. But he began his career in British film and television, playing cops and gangsters. Helen Mirren, who starred opposite him in his first major role, The Long Good Friday, and onstage in The Duchess of Malfi, penned a glowing tribute for The Guardian. “London,” she wrote, “will miss one of her best and most loving sons, and Britain will miss a man to be proud of.”

Mirren’s sentiments were echoed by British actors everywhere. Shane Meadows called him “the most generous actor I have ever worked with.” Stephen Woolley described Hoskins as a working-class hero. “With his talent, Bob gatecrashed the world of celebrity, and made all of us ordinary people feel a little better about ourselves.” It was a role he was seemingly born to play, despite his range. Hoskins was “a great actor,” writes Woolley, “yet unlike many actors he was first and foremost a courteous, sweet and caring human being. He could make monsters human and wring a smile out of any situation without a whisker of embarrassment.”

Those are the very qualities that endeared viewers to Hoskins’ first breakout character, Alf Hunt, a furniture removal man who struggled with reading and writing in On the Move, a kind of “Sesame Street for adults” that ran in 1976 on the BBC. The 10-minute shorts ran on Sunday afternoons “as part of the BBC’s adult education remit,” Mark Lawson writes at The Guardian. Hoskins’ performance brought to life for viewers “a proud man who has desperately disguised his learning difficulties.” It met a serious need among the nation’s populace.

“The show attracted 17 million viewers a week, (way beyond the size of its target audience),” notes a MetaFilter user. On the Move “helped make Hoskins famous. It was also responsible for persuading 70,000 people to sign up for adult literacy programmes.” Hoskins treasured the letters he received from viewers who decided to change their lives after seeing the show. They may well have done so because he gave his all to the character, as Lawson writes:

Handed a working-class stereotype (not for the last time in his career), Hoskins gave Alf a vulnerability and poignancy far beyond the requirements of a public information short. Apart from its intended audience of adults struggling with reading and writing, On the Move gained a large secondary following among literate viewers because, even then, Hoskins’ expressive face and growly voice made you want to watch and listen.

In each episode, Alf revealed his struggles to his friend Bert, played by Donald Gee. The show also featured inspiring interviews with adults who had taken adult literacy classes and appearances by special guest stars like Patricia Hayes and Martin Shaw (who both appear in the episode at the top). While other famous actors may disown early television work, Hoskins never did. On the Move “shared the qualities of his best stuff. Whereas most footage in Before They Were Famous type shows is calculated to be bathetic or embarrassing,” Hoskins’ earliest work does quite the opposite, explaining why he “went on to become the star he did.”

On the Move may also have earned Hoskins another title, one he might have cherished as much as any acting plaudit. George Auckland, who later directed the BBC’s adult education program, called him “the best educator Britain has produced” because of his wide reach among adults struggling with literacy in 1970s Britain. See an episode of On the Move at the top of the post and hear what commenters call “the catchiest theme song ever” just above.

Related Content:

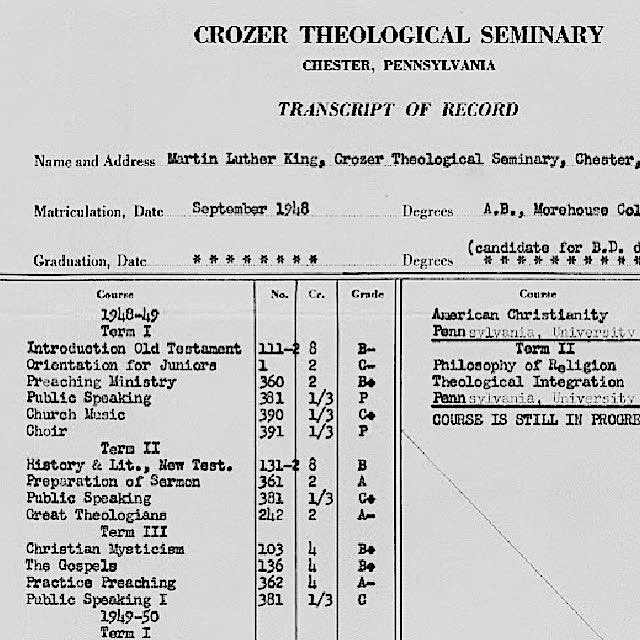

Take The Near Impossible Literacy Test Louisiana Used to Suppress the Black Vote (1964)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness