E + ducere: “To lead or draw out.” The etymological Latin roots of “education.” According to a former Jesuit professor of mine, the fundamental sense of the word is to draw others out of “darkness,” into a “more magnanimous view” (he’d say, his arms spread wide). As inspirational as this speech was to a seminar group of budding higher educators, it failed to specify the means by which this might be done, or the reason. Lacking a Jesuit sense of mission, I had to figure out for myself what the “darkness” was, what to lead people towards, and why. It turned out to be simpler than I thought, in some respects, since I concluded that it wasn’t my job to decide these things, but rather to present points of view, a collection of methods—an intellectual toolkit, so to speak—and an enthusiastic model. Then get out of the way. That’s all an educator can, and should do, in my humble opinion. Anything more is not education, it’s indoctrination. Seemed simple enough to me at first. If only it were so. Few things, in fact, are more contentious (Google the term “assault on education,” for example).

What is the difference between education and indoctrination? This debate rages back hundreds, thousands, of years, and will rage thousands more into the future. Every major philosopher has had one answer or another, from Plato to Locke, Hegel and Rousseau to Dewey. Continuing in that venerable tradition, linguist, political activist, and academic generalist extraordinaire Noam Chomsky, one of our most consistently compelling public intellectuals, has a lot to say in the video above and elsewhere about education.

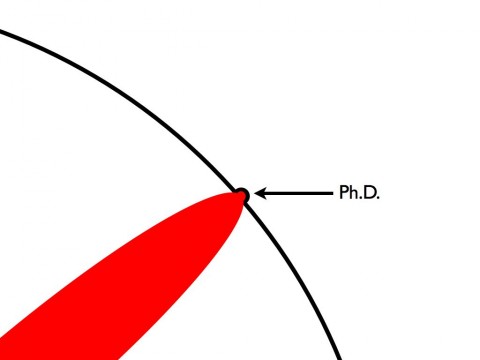

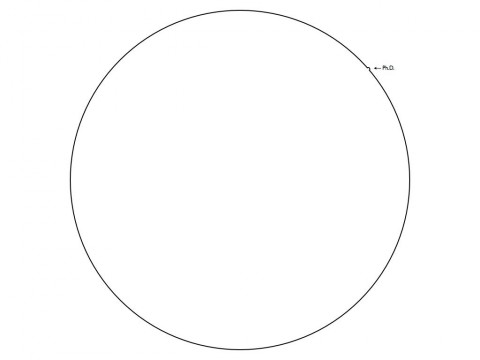

First, Chomsky defines his view of education in an Enlightenment sense, in which the “highest goal in life is to inquire and create. The purpose of education from that point of view is just to help people to learn on their own. It’s you the learner who is going to achieve in the course of education and it’s really up to you to determine how you’re going to master and use it.” An essential part of this kind of education is fostering the impulse to challenge authority, think critically, and create alternatives to well-worn models. This is the pedagogy I ended up adopting, and as a college instructor in the humanities, it’s one I rarely have to justify.

Chomsky defines the opposing concept of education as indoctrination, under which he subsumes vocational training, perhaps the most benign form. Under this model, “People have the idea that, from childhood, young people have to be placed into a framework where they’re going to follow orders. This is often quite explicit.” (One of the entries in the Oxford English Dictionary defines education as “the training of an animal,” a sense perhaps not too distinct from what Chomsky means). For Chomsky, this model of education imposes “a debt which traps students, young people, into a life of conformity. That’s the exact opposite of what traditionally comes out of the Enlightenment.” In the contest between these two definitions—Athens vs. Sparta, one might say—is the question that plagues educational reformers at the primary and secondary levels: “Do you train for passing tests or do you train for creative inquiry?”

Chomsky goes on to discuss the technological changes in education occurring now, the focus of innumerable discussions and debates about not only the purpose of education, but also the proper methods (a subject this site is deeply invested in), including the current unease over the shift to online over traditional classroom ed or the value of a traditional degree versus a certificate. Chomsky’s view is that technology is “basically neutral,” like a hammer that can build a house or “crush someone’s skull.” The difference is the frame of reference under which one uses the tool. Again, massively contentious subject, and too much to cover here, but I’ll let Chomsky explain. Whatever you think of his politics, his erudition and experience as a researcher and educator make his views on the subject well worth considering.

Josh Jones is a doctoral candidate in English at Fordham University and a co-founder and former managing editor of Guernica / A Magazine of Arts and Politics.

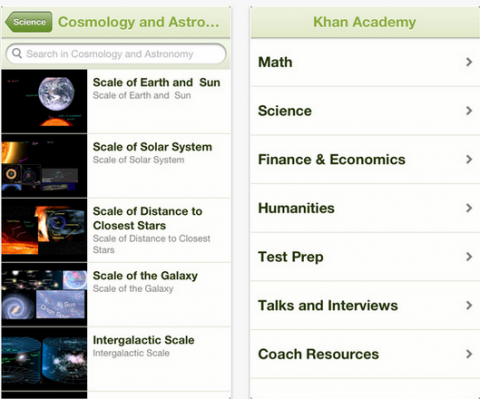

Non-profit Khan Academy, an organization dedicated to “providing a free world-class education for anyone anywhere,” does so primarily through online video courses and lectures. The over 3600 videos are free and access is open to anyone (anywhere), allowing K‑12 students to study math, science, computer science, finance & economics, humanities, and test prep. The organization was founded in 2006 by MIT and Harvard grad Salman Khan, who began by tutoring relatives and friends in Bangladesh while he worked as a hedge fund analyst in the States. His videos became so in-demand that he decided to quit his job and distribute them full-time, funded by donations from individuals and major donors like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Non-profit Khan Academy, an organization dedicated to “providing a free world-class education for anyone anywhere,” does so primarily through online video courses and lectures. The over 3600 videos are free and access is open to anyone (anywhere), allowing K‑12 students to study math, science, computer science, finance & economics, humanities, and test prep. The organization was founded in 2006 by MIT and Harvard grad Salman Khan, who began by tutoring relatives and friends in Bangladesh while he worked as a hedge fund analyst in the States. His videos became so in-demand that he decided to quit his job and distribute them full-time, funded by donations from individuals and major donors like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.