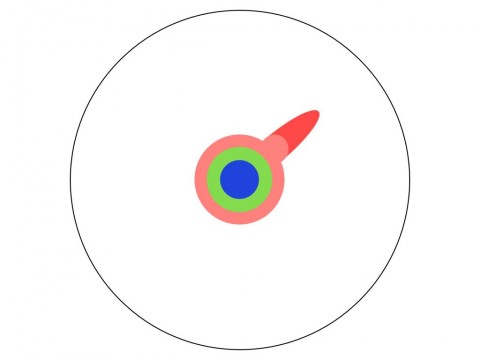

Image of Ron Paul, Don Black, Derek Black (right), via Wikimedia Commons

A native of West Palm Beach, Florida, Derek Black grew up in one of the most prominent white nationalist families in the United States. He’s the son of Don Black, a former grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. And he’s the godson of David Duke, “the most recognizable figure of the American radical right, a neo-Nazi, longtime Klan leader and now international spokesman for Holocaust denial” (per the Southern Poverty Law Center). In short, Derek Black had every reason to grow up a racist, and remain a racist from cradle to grave. But things didn’t turn out that way.

Below, you can hear Black explain how, as a young adult, he broke with white nationalism, leaving behind his family, friends and community. What laid the groundwork for that break? Going to a small liberal arts college, encountering new ideas, and meeting different people. In this recorded interview, he tells Michael Barbaro of The New York Times:

In 2010, I moved across the state and started college at this little liberal arts college in Florida, which was about three and a half hours from home and it was the first time that I had lived away from home. Nobody knew who I was and I did not volunteer who I was or anything about my background, I made friends, hung out with people and played my guitar on my balcony in my dorm. It was nice to come back from class and be able to talk about history or philosophy or whatever other subject and be around other people.…

I had a friend on campus who I had gotten to know during my first semester when nobody knew who I was, he was an observant Jew who had Shabbat dinners pretty regularly whenever he was in town on Friday night and he would invite people of atheists and all sorts of different religions. It was just a nice dinner. And so he actually invited me to one of the Shabbats, and I knew him, and so I brought wine…

He had read my posts on Stormfront [a white nationalist website created by Don Black] going back years — even the stuff when I was a teenager — and he doubted that he was going to convince me of anything, he just wanted to let me see a Jewish community thing so that if I was going to keep saying these anti-Semitic things that at least I had seen real Jews.

It was ultimately in private conversations with a person I met at the Shabbat dinners … we would talk about things. Not only white nationalism, but eventually white nationalism. And I would say, “This is what I believe about I.Q. differences, I have 12 different studies that have been published over the years, here’s the journal that’s put this stuff together, I believe that this is true, that race predicts I.Q. and that there were I.Q. differences in races.” And they would come back with 150 more recent, more well researched studies and explain to me how statistics works and we would go back and forth until I would come to the end of that argument and I’d say, Yes that makes sense, that does not hold together and I’ll remove that from my ideological toolbox but everything else is still there. And we did that over a year or two on one thing after another until I got to a point where I didn’t believe it anymore.

As you stream the interview below, spend some time thinking about the transformative power of a liberal arts education. Yes, more than an expedient business degree, it can change hearts and save lives.

Also pay attention to Black’s final thoughts on what Trump’s response to the Charlottesville drama did for the White nationalist movement: “I think Tuesday was the most important moment in the history of the modern white nationalist movement.” Trump “said there were good people in the white nationalist rally and he salvaged their message.”

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!