Every generation of schoolchildren no doubt first assumes homework to be a historically distinct form of punishment, developed expressly to be inflicted on them. But the parents of today’s miserable homework-doers also, of course, had to do homework themselves, as did their parents’ parents. It turns out that you can go back surprisingly far in history and still find examples of the menace of homework, as far back as ancient Egypt, a civilization from which one example of an out-of-classroom assignment will go on display at the British Library’s exhibition Writing: Making Your Mark, which opens this spring.

“Beginning with the origins of writing in Egypt, Mesopotamia, China and the Americas, the exhibition will explore the many manifestations, purposes and forms of writing, demonstrating how writing has continually enabled human progress and questioning the role it plays in an increasingly digital world,” says the British Library’s press release.

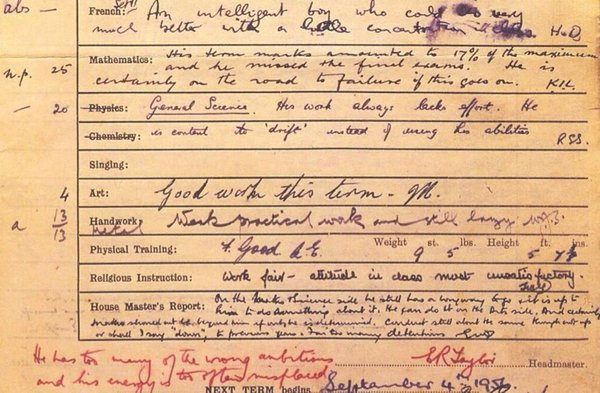

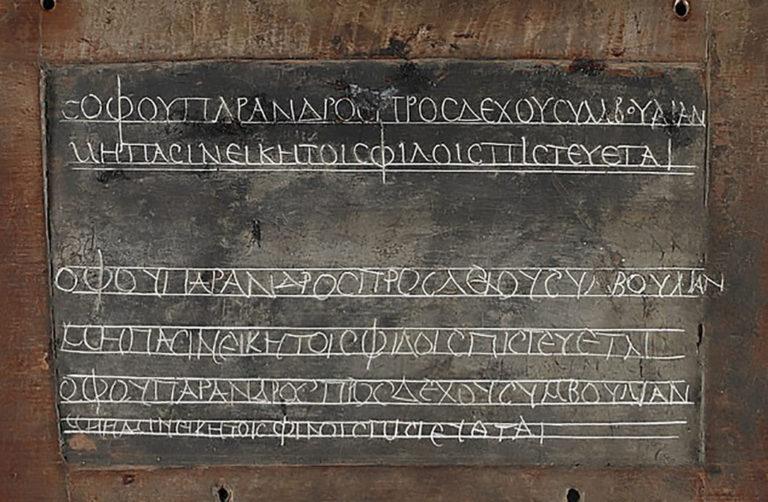

“From an ancient wax tablet containing a schoolchild’s homework as they struggle to learn their Greek letters to a Chinese typewriter from the 1970s, Writing: Making Your Mark will showcase over 30 different writing systems to reveal that every mark made – whether on paper or on a screen – is the continuation of a 5,000 year story and is a step towards determining how writing will be used in the future.”

That wax tablet, preserved since the second century A.D., bears Greek words that Livescience’s Mindy Weisberger describes as “familiar to any kid whose parents worry about them falling in with a bad crowd”: “You should accept advice from a wise man only” and “You cannot trust all your friends.” First acquired by the British Library in 1892 but not publicly displayed since the 1970s, the tablet’s surface preserves “a two-part lesson in Greek that provides a snapshot of daily life for a pupil attending primary school in Egypt about 1,800 years ago.” Its lines, “copied by this long-ago student were not just for practicing penmanship; they were also intended to impart moral lessons.”

But why Greek? “In the 2nd century A.D., when this lesson was written,” writes Smithsonian.com’s Jason Daley, “Egypt had been under Roman rule for almost 200 years following 300 years of Greek and Macedonian rule under the Ptolemy dynasty. Greeks in Egypt held a special status below Roman citizens but higher than those of Egyptian descent. Any educated person in the Roman world, however, would be expected to know Latin, Greek and — depending on where they lived — local or regional languages.” It was a bit like the situation today with the English language, which has become a requirement for educated people in a variety of cultures — and a subject especially loathed by many a homework-burdened student the world over.

via Livescience

Related Content:

You Could Soon Be Able to Text with 2,000 Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs

Try the Oldest Known Recipe For Toothpaste: From Ancient Egypt, Circa the 4th Century BC

The Turin Erotic Papyrus: The Oldest Known Depiction of Human Sexuality (Circa 1150 B.C.E.)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.