British You Tuber Nikolas “Lindybiege” Lloyd is a man of many, many interests.

Wing Chun style kung fu…

Children’s television produced in the UK between 1965 and 1975…

Ancient weaponry, chainmail, and historically accurate WWII model miniatures…

Actress Celia Johnson, star of the 1945 romantic drama Brief Encounter…

Evolutionary psychology…

…and it would appear, tennis.

But not the sort you’ll find played on the grass courts of Wimbledon, or for that matter, the hard courts of the US Open.

Lloyd is one of a select few who gravitate toward the version of the game that was known as the sport of kings.

It was, according to a 1553 guide, created, “to keep our bodies healthy, to make our young men stronger and more robust, chasing idleness, virtue’s mortal enemy, far from them and thus making them of a stronger and more excellent nature.”

Henry VIII was a talented and enthusiastic player in his youth, causing the Venetian Ambassador to rhapsodize, “it was the prettiest thing in the world to see him play; his fair skin glowing through a shirt of the finest texture.”

Henry’s second wife, the ill-fated Anne Boleyn, was also a fan of the sport, with money riding on the match she was watching when she was summoned to the Privy Council “by order of the King,” the first stop on her very swift journey to the Tower of London.

The sport’s roots reach all the way to the 11th and 12th centuries when monks and villagers in southern France were mad for jeu de paume, a tennis-like game predating the use of racquets, whose popularity eventually spread to the royals and aristocrats of Paris.

The game Lloyd tries his hand at above is now known as Real Tennis, a term invented in the 19th-century to distinguish it from the then-new craze for lawn tennis.

Mention “the sport of kings” these days and most folks will assume you’re referring to fox hunting or horse-racing.

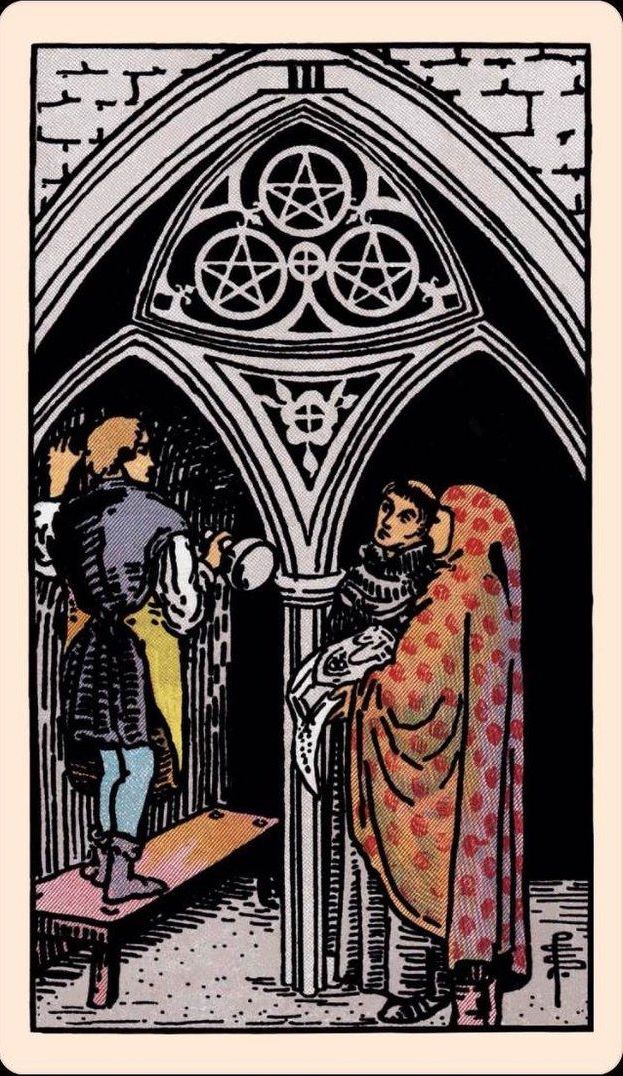

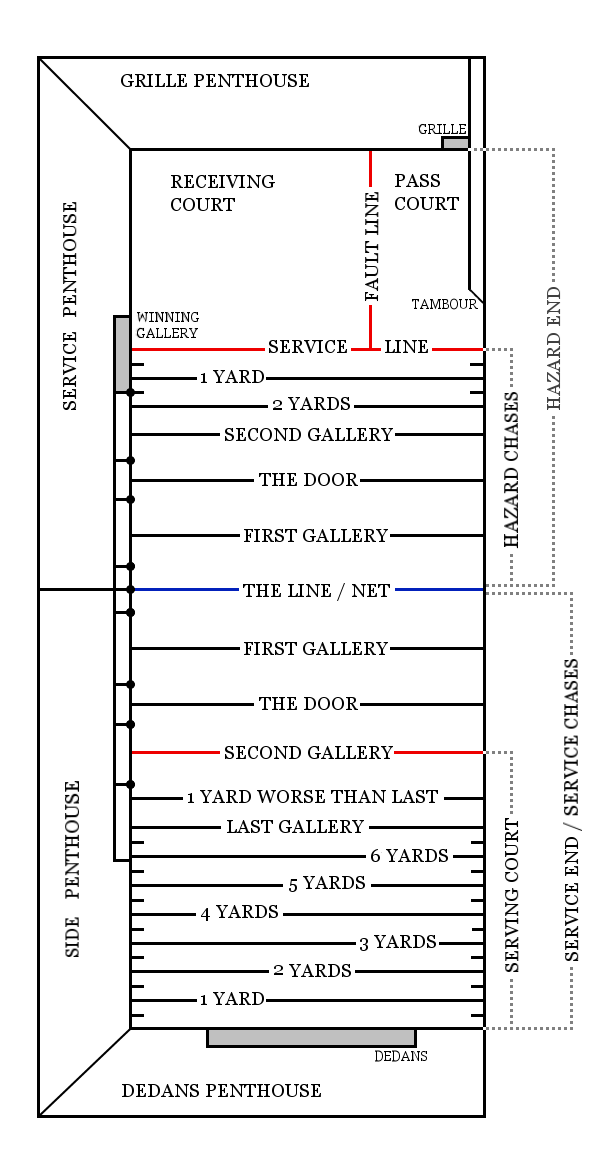

Mind you, real tennis is just as rarified. You won’t find it being played on any old (which is to say new) indoor court. It requires four irregularly sized walls, an asymmetrical layout, and a sloping penthouse roof. Behold the layout of a Real Tennis court by Atethnekos, compliments of English Wikipedia:

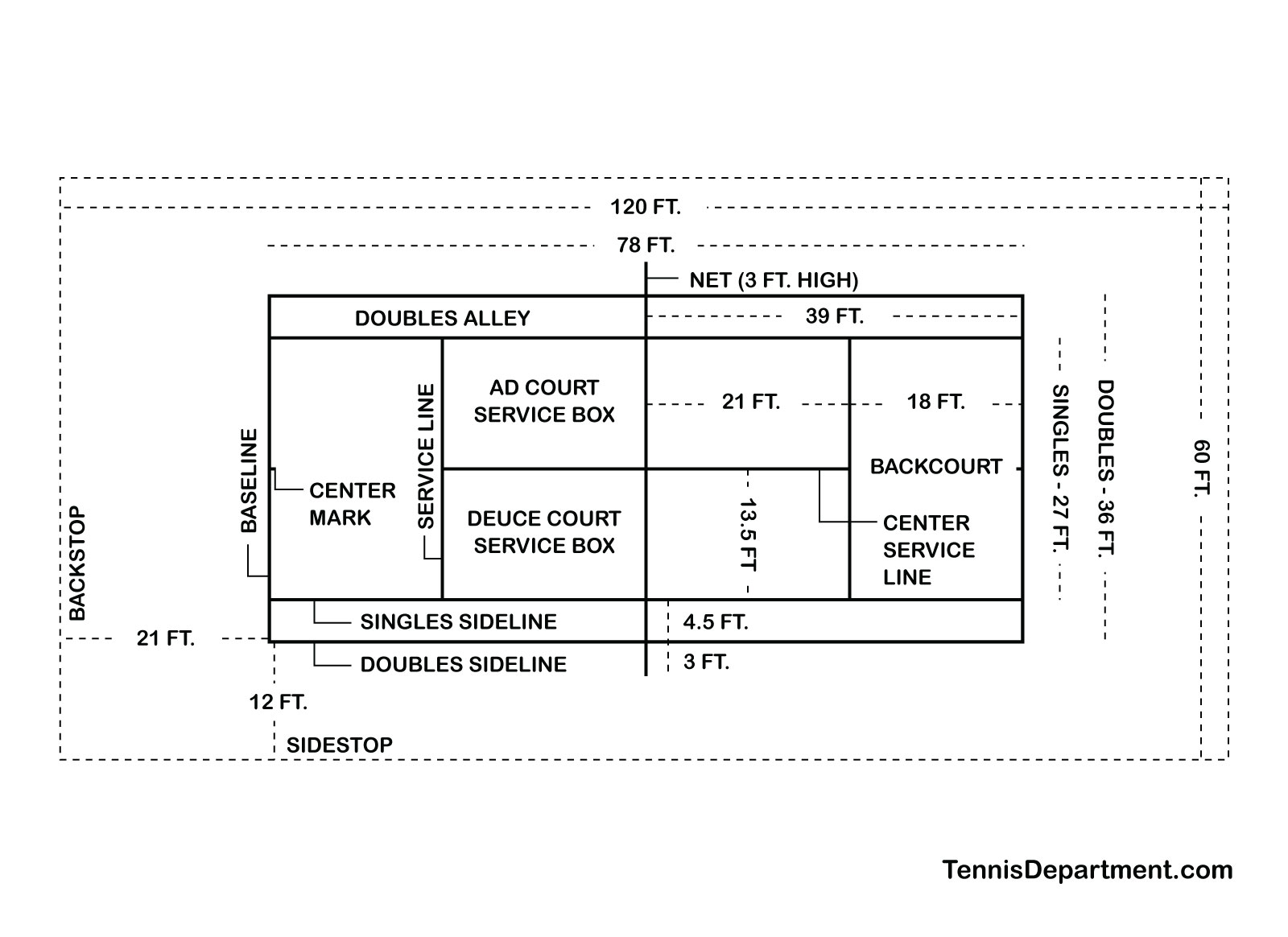

Compared to that, the Tennis Department’s diagram of the familiar modern set up seems like child’s play:

Other cognitive challenges for those whose version of tennis doesn’t extend back to medieval days: a slack net; lopsided, tightly strung, small raquets; and a gallery of waist-high screened “hazards,” that are spiritually akin to pinball targets, especially the one with the bell.

The handmade balls may look similar to your average mass-produced Penn or Wilson, but expect that each will be “unique in its particular quirks”:

They are not perfectly spherical and these seams stick out a little bit more here and there, which means that the bounce can be rather unpredictable. Because these are heavier and harder, they don’t swerve when you spin them in the air very much, but when they hit a wall and get a decent grip, the swerve can send them zinging off along the wall to great effect.

Once Lloyd has oriented viewers and himself to the court and equipment, Real Tennis pro Zak Eadle walks him through serving, scoring, and strategy in the form of chases.

Quoth Shakespeare’s Henry V:

His present, and your pains, we thank you for:

When we have match’d our rackets to these balls,

We will, in France, by God’s grace play a set,

Shall strike his father’s crown into the Hazard:

Tell him, he made a match with such a wrangler,

That all the Courts of France will be disturb’d with chases.

Even non-athletic types could find themselves fascinated by the historical context Lindybeige provides.

If you’re moved to take racquet in hand, there are a handful of Real Tennis courts in the USA, UK, Australia, and France where you might be able to try your luck.

The sport could use you. Estimates indicate that the number of players has dwindled to a mere 10,000. Surely someone is desperate for a partner.

Delve further into the world of Real Tennis on the International Real Tennis Professionals Association’s website.

Check out some of Lindybeige’s other interests on his YouTube channel.

Related Content:

What It’s Like to Actually Fight in Medieval Armor

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday