Ralph Steadman will always best be known—and for good reason—as the visual interpreter of Hunter S. Thompson’s druggy gonzo vision of American excess and hubris. As Colin Marshall wrote in a previous post on Steadman and Thompson’s powerful collaborative relationship, it’s hard to imagine a more “suitable visual accompaniment to the simultaneously clear- and wild-eyed sensibility of Thompsonian prose.” But the British artist has had a long and distinguished career, pre- and post-Thompson: illustrating Lewis Carroll’s surrealist classic Alice in Wonderland; creating limited edition DVD covers for the dark cult hit TV show Breaking Bad; making bullet-riddled collage art with counterculture hero William S. Burroughs…. To name just a few of his offbeat assignments over the years.

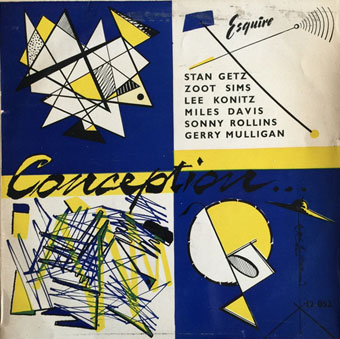

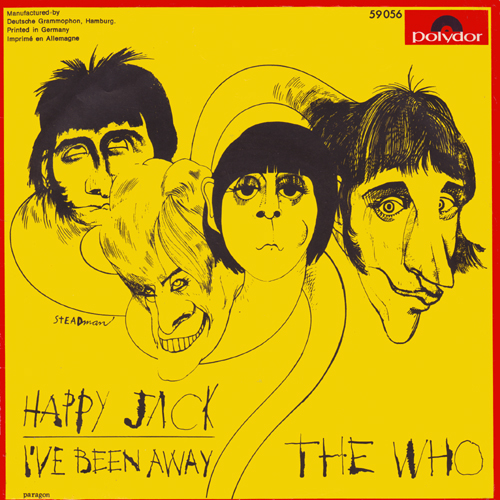

Today we bring you a lesser-known facet of Steadman’s work: designing album covers. As artist and illustrator John Coulthart notes in a post on Steadman’s album designs, he’s been at it since the mid-fifties, when—for example—he illustrated a release of Conception (top), “an underappreciated masterpiece of cerebral cool jazz” featuring the likes of Miles Davis, Stan Getz, and Sonny Rollins. Steadman’s abstract expressionist-inspired jazz covers soon gave way to more Steadmanesque, though still relatively tame, covers like that above for The Who’s single “Happy Jack”/“I’ve Been Away” from 1966.

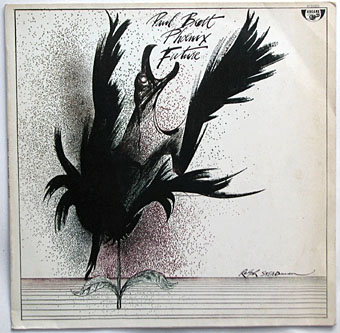

It’s not until the 70s, however—after he’d begun his collaboration with Thompson—that his album covers begin to take on the decidedly crazed look his work is known for, such as in the cover for Paul Brett’s Phoenix Future, above, from 1975.

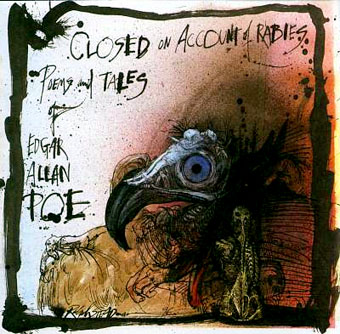

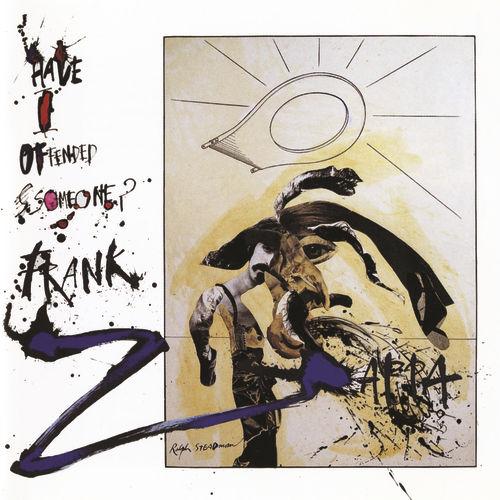

By 1997, Steadman seems to have perfected his inimitable riot of grotesque imagery, wild color palette, and unhinged black lines and lettering, as in the cover for Closed On Account Of Rabies: Poems And Tales Of Edgar Allan Poe, a compilation of Poe readings by stars like Christopher Walken, Iggy Pop, Marianne Faithfull, Jeff Buckley, and Abel Ferrara, which we’ve featured on OC before. The artists represented here are—as in his work with Thompson and Burroughs—perfectly fitting for Steadman’s sensibility. So, of course, is the clean-living but otherwise totally bonkers Frank Zappa, whose 1997 Have I Offended Someone? received the Steadman treatment, as you can see below.

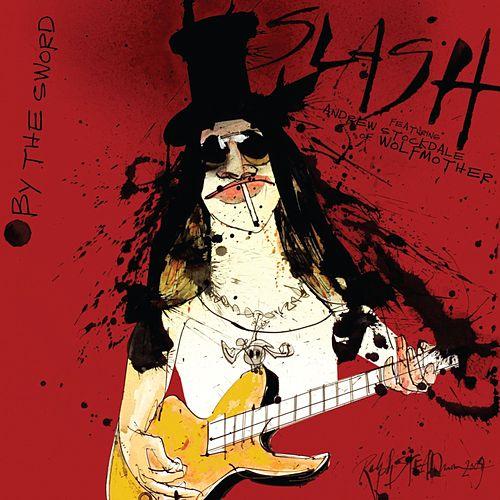

In the past few years, Steadman has mellowed a bit, if you could call it that, and his work has taken on a slightly more refined character. His Breaking Bad illustrations seem restrained by the standards of his work with Thompson or Zappa. And in a 2010 cover for Slash’s first official single, “By the Sword,” below, he reigns in some of his wilder graphic impulses while retaining all of the stylist signatures he developed over the decades.

Steadman has always been a one-of-a-kind illustrator. In his album cover design, we can perhaps best watch his work evolve. As Coulthart writes, “the style of the early sleeves is markedly different to the angry, splattery creations that made his name, and without a signature you’d be unlikely to recognise the artist.” See many more Steadman album covers over at Coulthart’s excellent blog.

Related Content:

Breaking Bad Illustrated by Gonzo Artist Ralph Steadman

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness