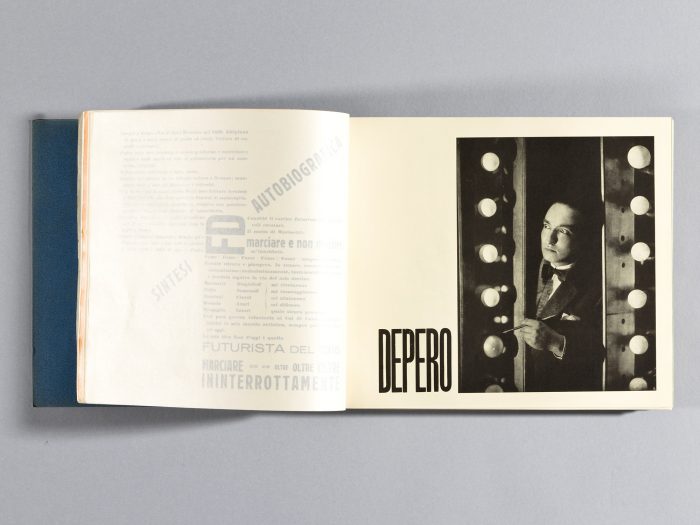

You can try to dismantle your e‑reader, but you can’t unscrew an eBook. Despite having cast his artistic mind, as did his fellow 20th-century Italian Futurists, forcefully into the world to come, could Fortunato Depero have imagined that such a question would arise in the 21st? The Trentino-born painter, writer, sculptor, and graphic designer, led a highly creative life, producing no work more enduring than the instantly recognizable Campari Soda bottle. But just last year, a group of enthusiasts successfully raised more than $250,000 on Kickstarter to bring back into print Depero’s second-best-known creation: Depero Futurista, also known as “The Bolted Book.”

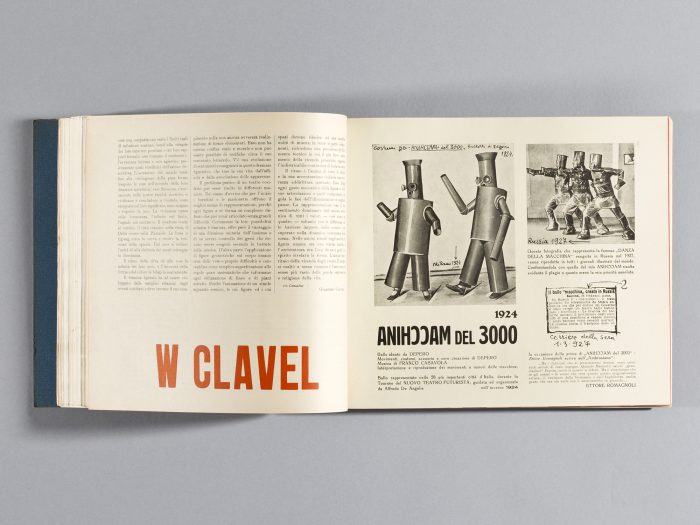

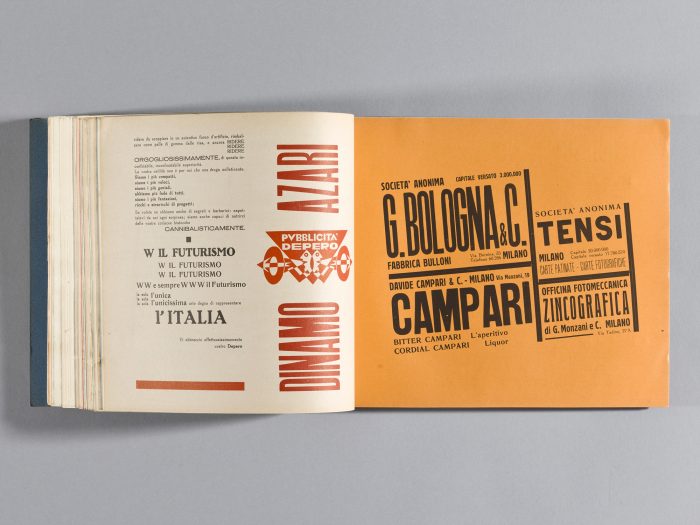

Designed by Depero as “a kind of portable museum or calling card, a portfolio of his career to date — including paintings, sculptures, textile and architectural designs, theater and advertising work, wordplays, manifestoes, and reviews he received in many different languages,” Depero Futurista, as described by the reprint project’s web site, also shows off his “skills as a designer and typographical wizard.”

These impress as much in 2017 as they must have at the time of the book’s first publication ninety years ago in Milan, and the binding method remains as distinctive: “Comprising 240 pages, the book is secured by two large industrial aluminum bolts that when removed allow for the pages to be removed, rearranged, or exhibited individually.”

You may never have heard of Depero, but today’s most respected designers certainly have, and some of them appear in the project’s Kickstarter promo video giving testimonials not just to the importance of Depero’s aesthetic achievements in general but The Bolted Book in particular. It offers a “bridge between the past and the future” in design, an innovative, ironic, and playful use of the “machine aesthetic,” and evidence that “Depero, despite his idiosyncrasies, was one of the most creative of the Futurists.” (It also, of course, holds the title of the first-ever book “bolted by two giant clasps.”) But perhaps the most compelling comes from Stefan Sagmeister: “This book contains the favorite packaging of my favorite drink, Campari Soda. For this alone, it should be contributed at properly — Kickstarted.”

Successfully Kickstarted, the new and 100 percent faithful reprint of Depero Futurista (whose few surviving originals sit mostly in institutional collections) should arrive in July of this year. Even if you can’t get your hands on a real, bolted copy just yet, you can view each and every one of its pages on the reprint project’s site. All the brilliance on display does make one regret that the Futurist movement ended with the tarnish of Fascism. But now that references to the latter seems to have re-entered the public conversation, maybe the time has come to bring back the vigorous, forward-looking artistic inventiveness of the former as a kind of countervailing inspiration.

Related Content:

Download 20 Free eBooks on Design from O’Reilly Media

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.