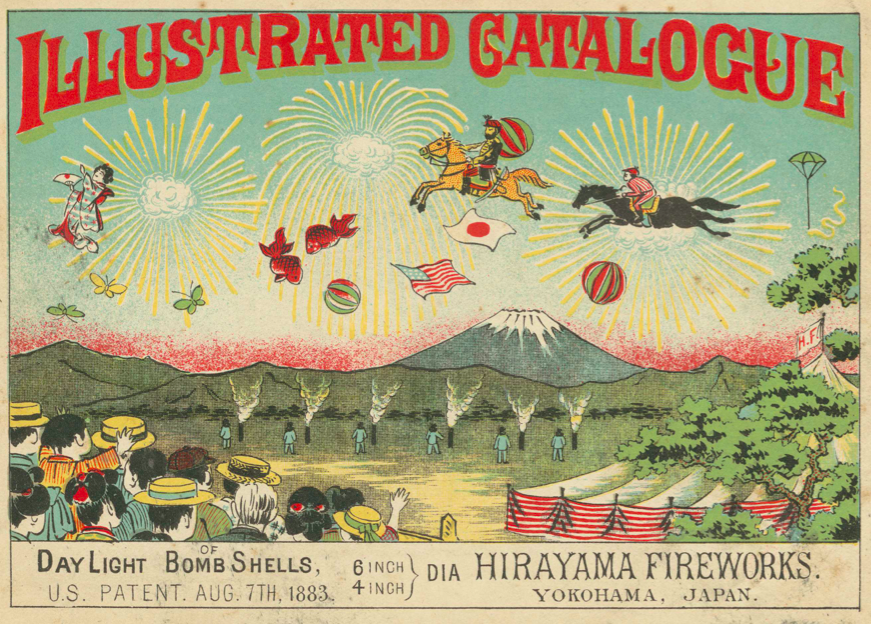

Medieval conceptions of hell may have little effect on the laws and social mores of our secular age. But they sure as hell did in the late 15th century, when the first illustrated editions of Dante’s Inferno appeared. A 1481 edition contained art based on a series of unfinished illustrations by Renaissance master Sandro Botticelli. In 1491, the first fully-illustrated edition of the Inferno arrived. As were most printed works at the time, these books were elaborate and expensive, reflecting the very serious treatment the subject of Dante’s work received.

Centuries later, Dante’s work has not lost its effect on our imaginations. Though most people are far less likely to entertain belief in a giant corkscrew pit beneath the earth full of tortured souls, it remains a vivid, chilling (so to speak) metaphor. The epic poem’s language moves and entrances us; its psychological insights dazzle; its formal innovations continue to awe; and its images still shock, amuse, and terrify.

Every decade, it seems, produces some new, fresh visual take on the Inferno, from Botticelli to the stunning renderings of William Blake, Gustave Doré, Alberto Martini, Salvador Dali, Robert Rauschenberg.…

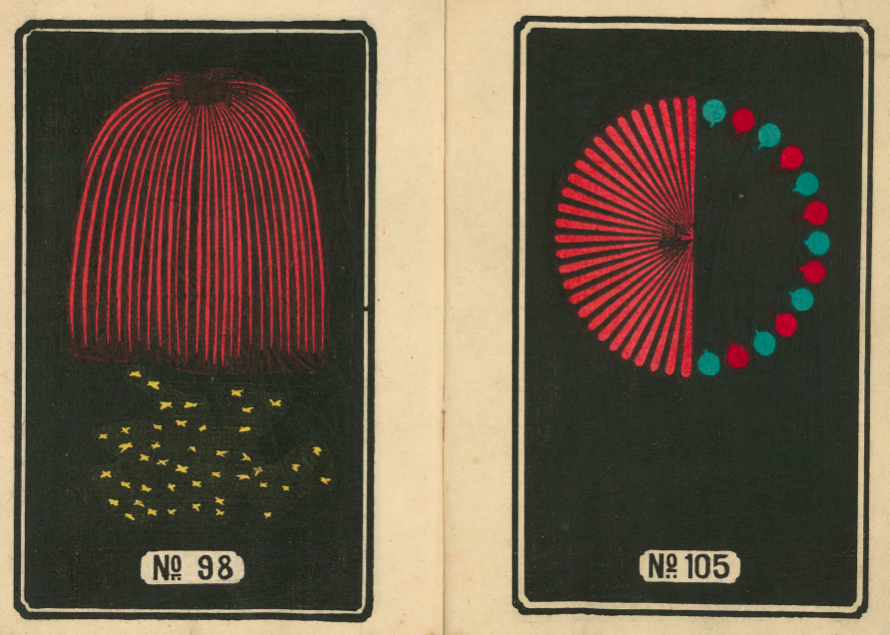

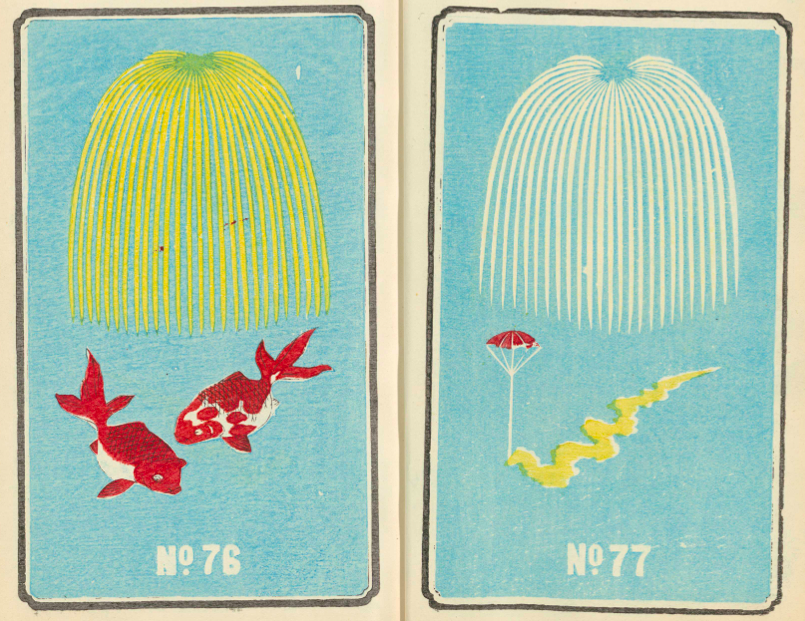

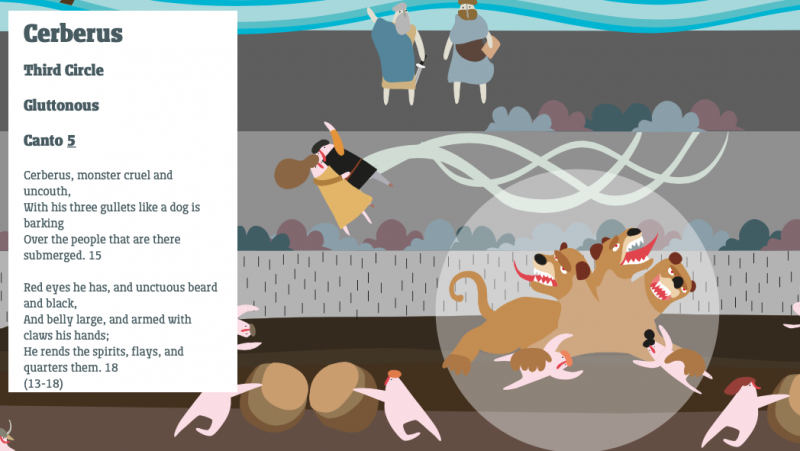

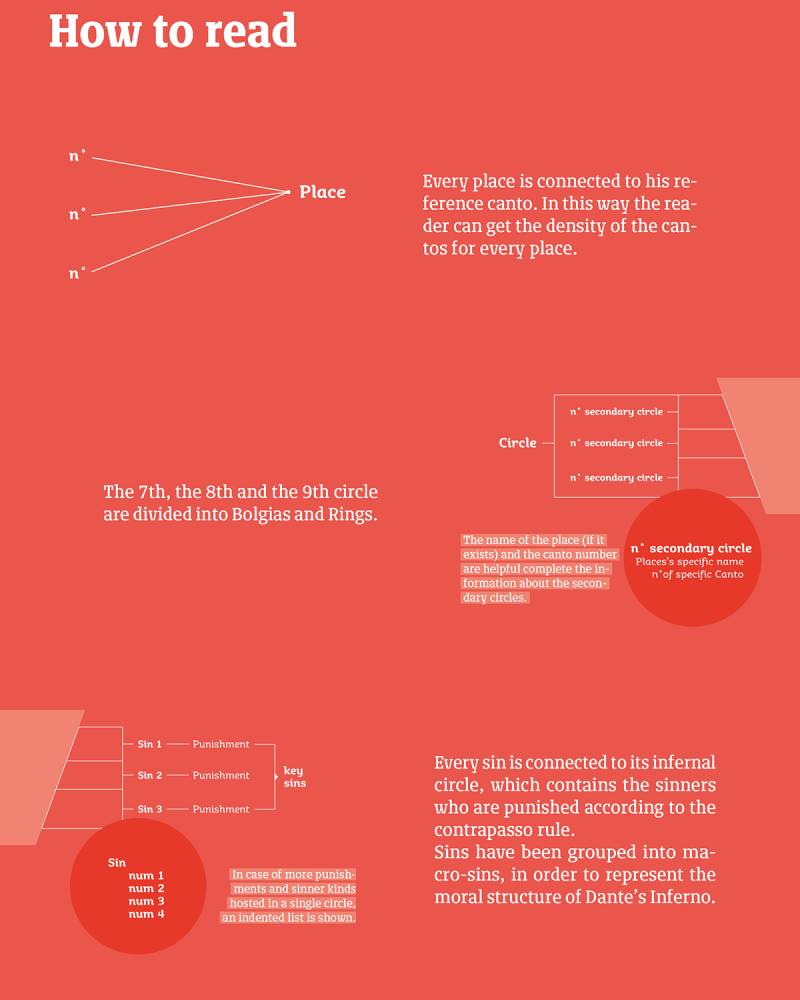

This is daunting company, and the online, interactive companion to the Inferno you see screen-shotted here does not attempt to join their ranks. Its charming, children’s‑book-graphic visual presentation takes a G‑rated approach, ditching accurate human anatomy and horrific violence for a cartoonish video game romp through hell that makes it seem like a super fun, if super weird, place to visit. Created by Alpaca, an Italian design cooperative, and design studio Molotro, the tool aims to be “a synsemic access point to Dante’s literature, aiding its study.”

What it lacks in visual high seriousness, it makes up for in utility. In this brilliantly simple design you can leap from Canto to Canto, learn the circle each one covers, the kind of sinners who inhabit it, and the main characters in each. Click on selected figures in the graphic to see character names and quoted excerpts from the poem. A much longer list of characters serves as an index, quickly linking each name to a Canto, quotation, circle, and sin. The Italian site links to the original poem on Wikipedia. The English version’s annotations link to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1867 translation.

Access Cantos and Characters in menus at the top of the main page or use the zoom button to move closer into any point in the topographical map and begin clicking on cartoon figures in various stages of tortured distress. See Behance for an illustrated guide through the online Inferno, a comical-looking tool with very serious applications for students of Dante’s poem. If you’re new to the Inferno, dive right in here. Hell awaits, as it has for millions of fascinated readers for 800 years.

Related Content:

A Free Course on Dante’s Divine Comedy from Yale University

A Digital Archive of the Earliest Illustrated Editions of Dante’s Divine Comedy (1487–1568)

Alberto Martini’s Haunting Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy (1901–1944)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness