Rings with discreet dual purpose have been in use since before the common era, when Hannibal, facing extradition, allegedly ingested the poison he kept secreted behind a gemstone on his finger. (More recently, poison rings gave rise to a popular Game of Thrones fan theory…)

Victorians prevented their most closely kept secrets—illicit love letters, perhaps? Last wills and testaments?—from falling into the wrong hands by wearing the keys to the boxes containing these items concealed in signet rings and other statement-type pieces.

A tiny concealed blade could be lethal on the finger of a skilled (and no doubt, beautiful) assassin. These days, they might be used to collect a bit of one’s attacker’s DNA.

Enter the fictional world of James Bond, and you’ll find a number of handy dandy spy rings including one that doubles as a camera, and another capable of shattering bulletproof glass with a single twist.

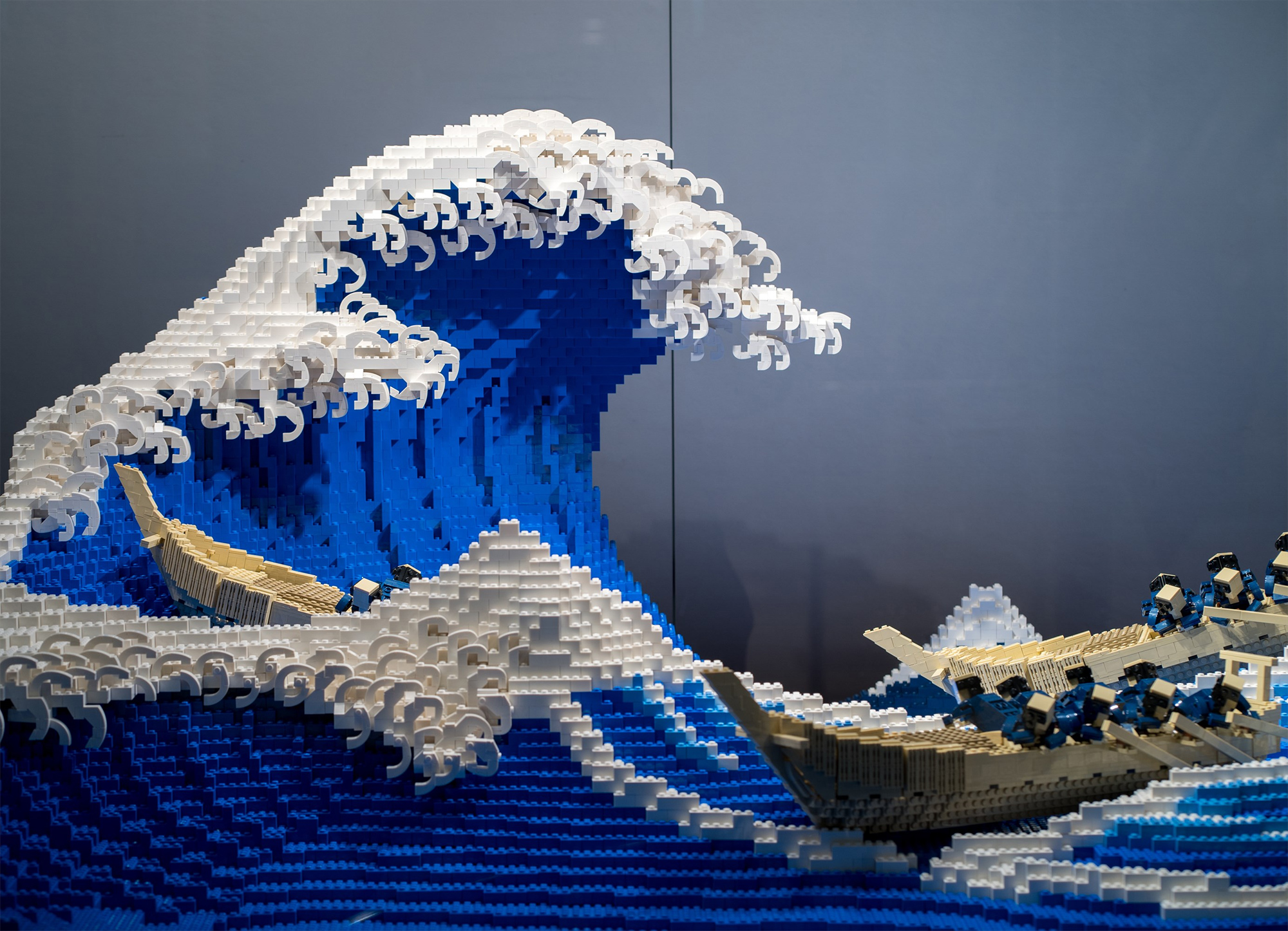

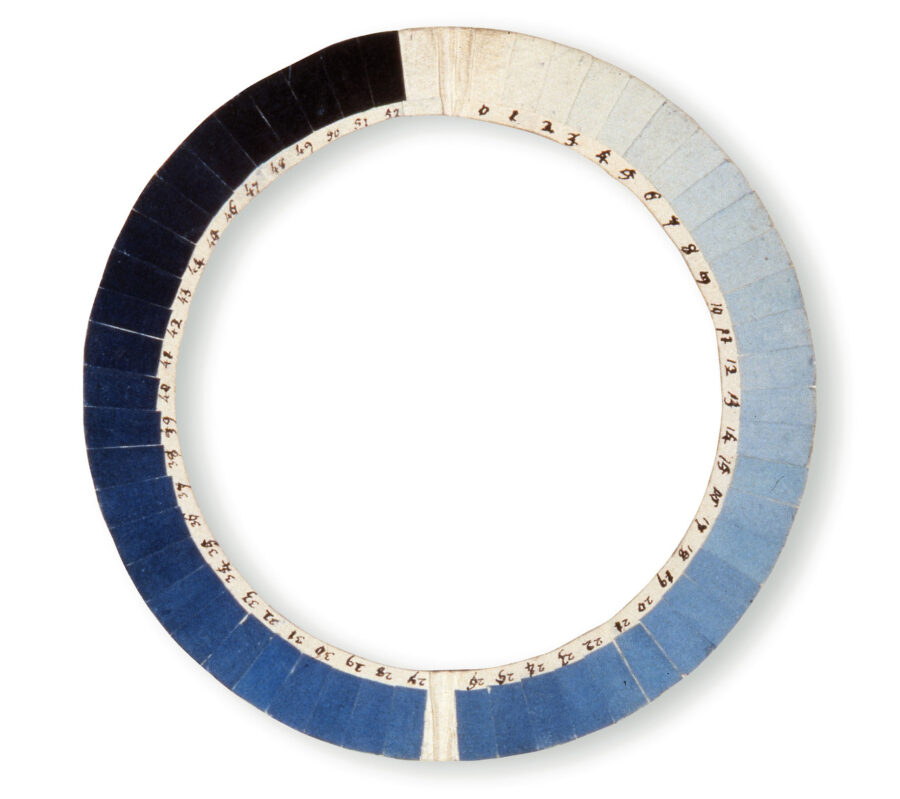

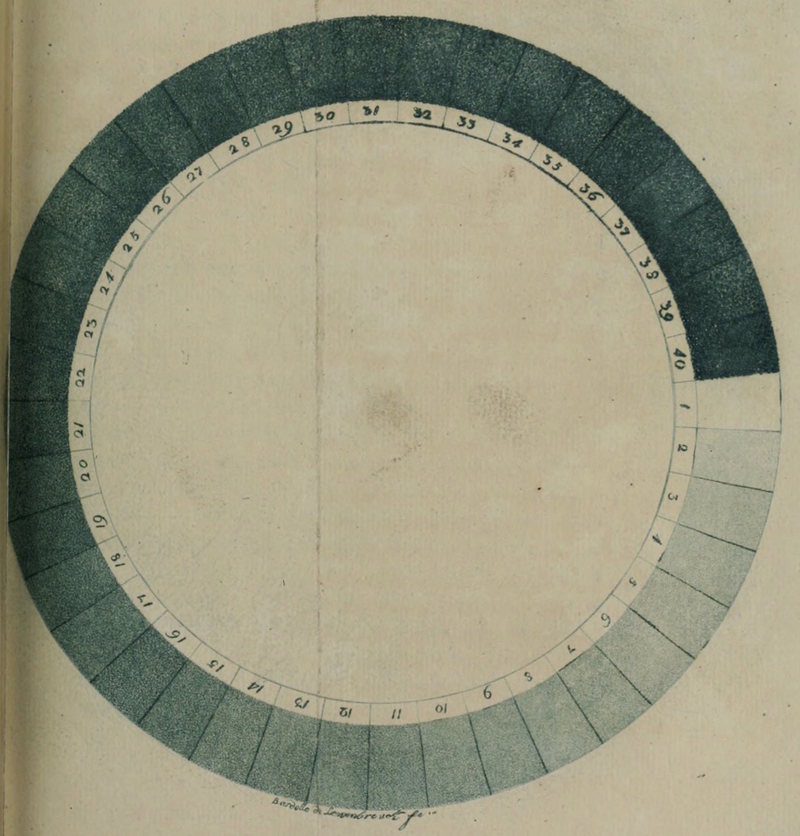

Armillary sphere rings like the ones in the British Museum’s collection and the Swedish Historical Museum (top) serve a more benign purpose. Folded together, the two-part outer hoop and three interior hoops give the illusion of a simple gold band. Slipped off the wearer’s finger, they can fan out into a physical model of celestial longitude and latitude.

Art historian Jessica Stewart writes that in the 17th century, rings such as the above specimen were “used by astronomers to study and make calculations. These pieces of jewelry were considered tokens of knowledge. Inscriptions or zodiac symbols were often used as decorative elements on the bands.”

The armillary sphere rings in the British Museum’s collection are made of a soft high alloy gold.

Jewelry-loving modern astronomers seeking an old school finger-based calculation tool that really works can order armillary sphere rings from Brooklyn-based designer Black Adept.

via My Modern Met

Related Content:

A 9th Century Manuscript Teaches Astronomy by Making Sublime Pictures Out of Words

The Ancient Astronomy of Stonehenge Decoded

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. She most recently appeared as a French Canadian bear who travels to New York City in search of food and meaning in Greg Kotis’ short film, L’Ourse. Follow her @AyunHalliday.