What triggered the worst impulses of the Internet last week?

The world’s first photo of a black hole, which proved the presence of troll life here on earth, and confirms that female scientists, through no fault of their own, have a much longer way to go, baby.

If you want a taste, sort the comments on the two year old TED Talk, above, so they’re ordered “newest first.”

Katie Bouman, soon-to-be assistant professor of computing and mathematical sciences at the California Institute of Technology, was a PhD candidate at MIT two years ago, when she taped the talk, but she could’ve passed for a nervous high schooler competing in the National Science Bowl finals, in clothes borrowed from Aunt Judy, who works at the bank.

The focus of her studies were the ways in which emerging computational methods could help expand the boundaries of interdisciplinary imaging.

Prior to last week, I’m not sure how well I could have parsed the focus of her work had she not taken the time to help less STEM-inclined viewers such as myself wrap our heads around her highly technical, then-wholly-theoretical subject.

What I know about black holes could still fit in a thimble, and in truth, my excitement about one being photographed for the first time pales in comparison to my excitement about Game of Thrones returning to the airwaves.

Fortunately, we’re not obligated to be equally turned on by the same interests, an idea theoretical physicist Richard Feynman promoted:

I’ve always been very one-sided about science and when I was younger I concentrated almost all my effort on it. I didn’t have time to learn and I didn’t have much patience with what’s called the humanities, even though in the university there were humanities that you had to take. I tried my best to avoid somehow learning anything and working at it. It was only afterwards, when I got older, that I got more relaxed, that I’ve spread out a little bit. I’ve learned to draw and I read a little bit, but I’m really still a very one-sided person and I don’t know a great deal. I have a limited intelligence and I use it in a particular direction.

I’m pretty sure my lack of passion for science is not tied to my gender. Some of my best friends are guys who feel the same. (Some of them don’t like team sports either.)

But I couldn’t help but experience a wee thrill that this young woman, a science nerd who admittedly could’ve used a few theater nerd tips regarding relaxation and public speaking, realized her dream—an honest to goodness photo of a black hole just like the one she talked about in her TED Talk, “How to take a picture of a black hole.”

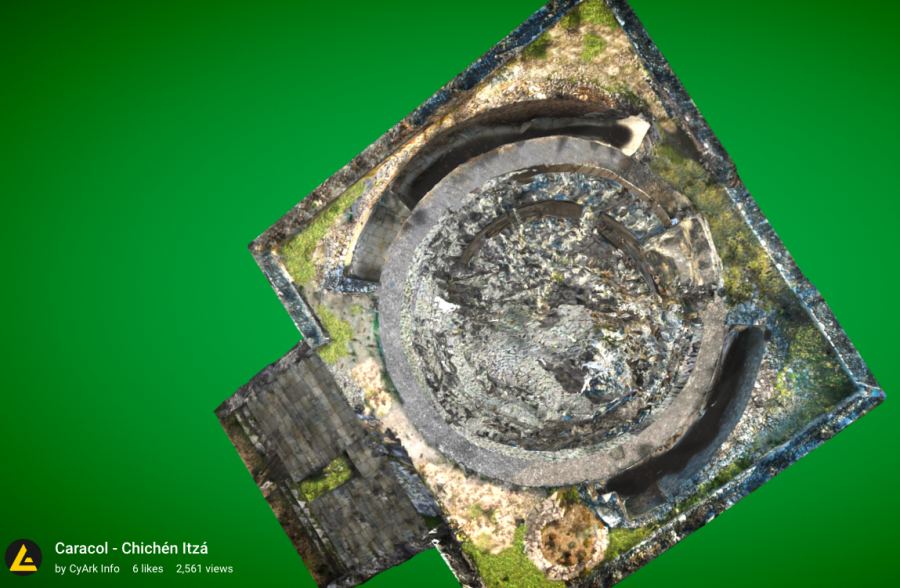

Bouman and the 200+ colleagues she acknowledges and thanks at every opportunity, achieved their goal, not with an earth-sized camera but rather a network of linked telescopes, much as she had described two years earlier, when she invoked disco balls, Mick Jagger, oranges, selfies, and a jigsaw puzzle in an effort to help people like me understand.

Look at that sucker (or, more accurately, its shadow!) That thing’s 500 million trillion kilometers from Earth!

(That’s much farther than King’s Landing is from Winterfell.)

I’ll bet a lot of elementary science teachers, be they male, female, or non-binary, are going to make science fun by having their students draw pictures of the picture of the black hole.

If we could go back (or forward) in time, I can almost guarantee that mine would be among the best because while I didn’t “get” science (or gym), I was a total art star with the crayons.

Then, crafty as Lord Petyr Baelish when presentation time rolled around, I would partner with a girl like Katie Bouman, who could explain the science with winning vigor. She genuinely seems to embrace the idea that it “takes a village,” and that one’s fellow villagers should be credited whenever possible.

(How did I draw the black hole, you ask? Honestly, it’s not that much harder than drawing a doughnut. Now back to Katie!)

Alas, her professional warmth failed to register with legions of Internet trolls who began sliming her shortly after a colleague at MIT shared a beaming snapshot of her, taken, presumably, with a regular old phone as the black hole made its debut. That pic cemented her accidental status as the face of this project.

Note to the trolls—it wasn’t a dang selfie.

“I’m so glad that everyone is as excited as we are and people are finding our story inspirational,’’ Bouman told The New York Times. “However, the spotlight should be on the team and no individual person. Focusing on one person like this helps no one, including me.”

Although Bouman was a junior team member, she and other grad students made major contributions. She directed the verification of images, the selection of imaging parameters, and authored an imaging algorithm that researchers used in the creation of three scripted code pipelines from which the instantly-famous picture was cobbled together.

As Vincent Fish, a research scientist at MIT’s Haystack Observatory told CNN:

One of the insights Katie brought to our imaging group is that there are natural images. Just think about the photos you take with your camera phone—they have certain properties.… If you know what one pixel is, you have a good guess as to what the pixel is next to it.

Hey, that makes sense.

As The Verge’s science editor, Mary Beth Griggs, points out, the rush to defame Bouman is of a piece with some of the non-virtual realities women in science face:

Part of the reason that some posters found Bouman immediately suspicious had to do with her gender. Famously, a number of prominent men like disgraced former CERN physicist Alessandro Strumia have argued that women aren’t being discriminated against in science — they simply don’t like it, or don’t have the aptitude for it. That argument fortifies a notion that women don’t belong in science, or can’t really be doing the work. So women like Bouman must be fakes, this warped line of thinking goes…

Even I, whose 7th grade science teacher tempered a bad grade on my report card by saying my interest in theater would likely serve me much better than anything I might eek from her class, know that just as many girls and women excel at science, technology, engineering, and math as excel in the arts. (Sometimes they excel at both!)

(And power to every little boy with his sights set on nursing, teaching, or ballet!)

(How many black holes have the haters photographed recently?)

Griggs continues:

Saying that she was part of a larger team doesn’t diminish her work, or minimize her involvement in what is already a history-making project. Highlighting the achievements of a brilliant, enthusiastic scientist does not diminish the contributions of the other 214 people who worked on the project, either. But what it is doing is showing a different model for a scientist than the one most of us grew up with. That might mean a lot to some kids — maybe kids who look like her — making them excited about studying the wonders of the Universe.

Related Content:

Watch a Star Get Devoured by a Supermassive Black Hole

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in New York City tonight for the next installment of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday.