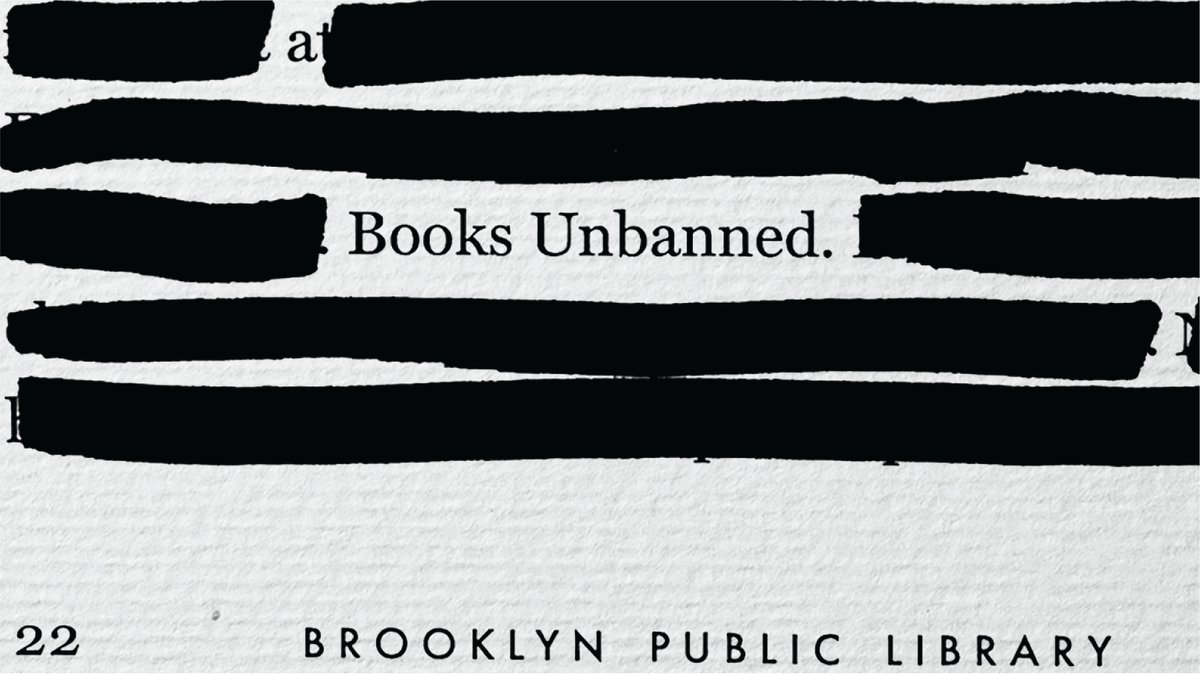

We have covered it before: school districts across the United States are increasingly censoring books that don’t align with conservative, white-washed visions of the world. Art Spiegelman’s Maus, The Illustrated Diary of Anne Frank, Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, and Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird–these are some of the many books getting pulled from library shelves in American schools. In response to this concerning trend, the Brooklyn Public Library has made a bold move: For a limited time, the library will offer a free eCard to any person aged 13 to 21 across the United States, allowing them free access to 500,000 digital books, including many censored books. The Chief Librarian for the Brooklyn Public Library, Nick Higgins said:

A public library represents all of us in a pluralistic society we exist with other people, with other ideas, other viewpoints and perspectives and that’s what makes a healthy democracy — not shutting down access to those points of view or silencing voices that we don’t agree with, but expanding access to those voices and having conversations and ideas that we agree with and ideas that we don’t agree with.

And he added:

This is an intellectual freedom to read initiative by the Brooklyn Public Library. You know, we’ve been paying attention to a lot of the book challenges and bans that have been taking place, particularly over the last year in many places across the country. We don’t necessarily experience a whole lot of that here in Brooklyn, but we know that there are library patrons and library staff who are facing these and we wanted to figure out a way to step in and help, particularly for young people who are seeing, some books in their library collections that may represent them, but they’re being taken off the shelves.

As for how to get the Brooklyn Public Library’s free eCard, their Books Unbanned website offers the following instructions: “individuals ages 13–21 can apply for a free BPL eCard, providing access to our full eBook collection as well as our learning databases. To apply, email bo***********@bk**********.org.” In short, send them an email.

You can find a list of America’s most frequently banned books at the website of the American Library Association.

Note: We first posted about this initiative during the dog days of last August. But it seemed worth mentioning this program while school’s in full swing. Hence why we’re flagging Books Unbanned again.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content

Texas School Board Bans Illustrated Edition of The Diary of Anne Frank

The 850 Books a Texas Lawmaker Wants to Ban Because They Could Make Students Feel Uncomfortable

Umberto Eco Makes a List of the 14 Common Features of Fascism