You may have received an email from your favorite online retailer, your boss, university president, or the CEO of your bank: “It has come to our attention that racism is real, and it is really, really bad.” Opportunism is real too, but a significant number of individuals seem to have finally drawn the same conclusion and feel morally compelled to do something about an epidemic that has—very discriminately—killed tens of thousands of black, indigenous, and people of color in the U.S. through the unequal distribution of medical resources, and dozens more at the hands of the police and racist vigilantes. That’s only in the past three months.

But racism isn’t new; the current conflict has been on its way for a very long time. How long? Anti-racist scholar and activist Ibram X. Kendi, author of the National Book Award-Winning Stamped from the Beginning, would say from the country’s earliest settlement and enslavement of African people. “For nearly six centuries,” he writes, “antiracist ideas have been pitted against two kinds of racist ideas: segregationist and assimilationist,” Kendi wrote during the protests in Ferguson and other U.S. cities. At the time, antiracists were largely characterized in mainstream media as fringe agitators, naïve Gen‑Z neophytes, and possible foreign agents, not “real Americans.”

How things have changed in six years. Antiracism has become a default position, all of a sudden, for perhaps the first time in U.S. history, so much so that every company and institution has issued some sort of statement in support of Black Lives Matter, and everyone is collecting and sharing Anti-Racist Reading Lists, nearly all of which contain Kendi’s follow-up book, last year’s How to Be an Anti-Racist (which he discusses above with Brené Brown). How long this will last is anyone’s guess, but it is without a doubt a cultural sea change a long time in the making.

Kendi and White Fragility author Robin DiAngelo are the “mac daddies of the bunch” of recent antiracist authors, Lauren Michele Jackson writes at Vulture, and it’s become a crowded field as more and more Americans attempt to come to grips with a national history many of them are learning for the first time. As Kendi and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, creator of the 1619 project, discuss on Chris Hayes’ podcast at the top, the country’s past as it is taught to us and as it happened are two entirely different things. Antiracism has always recognized the vicious, ceaseless murder, disenfranchisement, and ransacking of black and brown people, and has pushed against the narratives that deny or excuse these acts.

Carol Anderson, author of White Rage, has given us one of the most raw, compelling, and exhaustively researched accounts of the violence of Reconstruction and the lynchings of the early 20th century. Above, she links the murder of 25-year-old Ahmaud Arbery and recent police killings to the shockingly brutal racism that followed the Civil War. Anderson’s book also routinely appears on suggested reading lists, and well it should. All of these scholars and authors have produced accessible work full of histories one might previously have only encountered in graduate-level college and university courses. It is essential information for people committed to overturning racist systems, which is exactly why it has been left out of the textbooks.

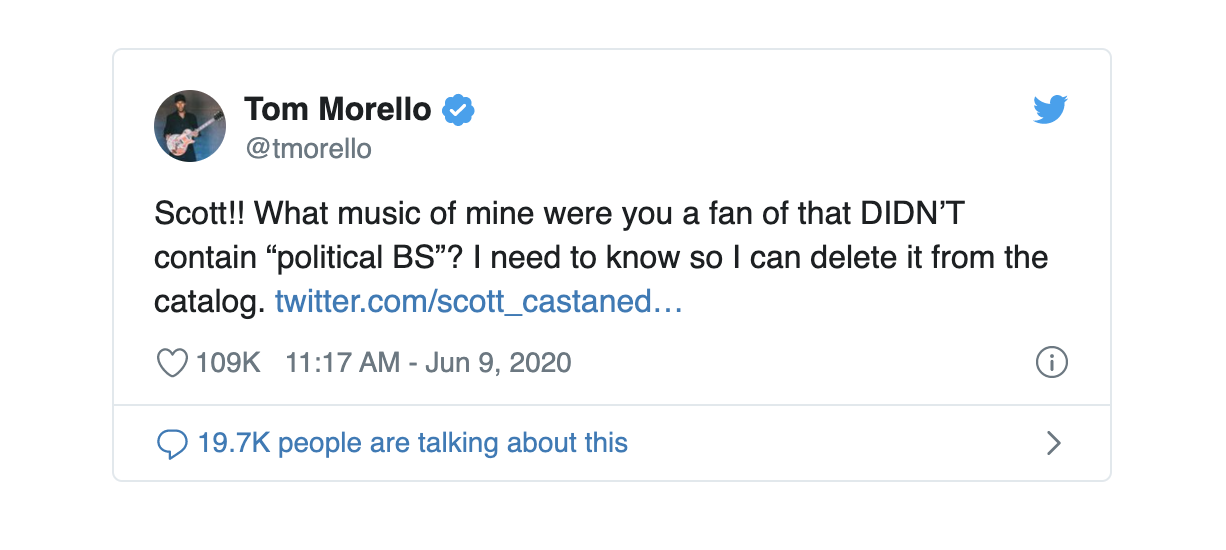

For all the urgency of education, the anti-racist booklist is an ambiguous kind of currency. Jackson wonders what function it serves, exactly. Reading lists can be an erudite brush-off, a polite way of saying, “go away and read a book.” They can be a way to signal mastery and work for online merit badges rather than real beneficial action. They can “feel good to solicit, good to mete out, but someone at some point has to get down to the business of reading. And there, between giving and receiving, lies a great gulf. No one can quite account for what happens. Reading, hopefully, but you never can be sure.”

Jackson’s critique of the anti-racist reading list is worth reading before engaging with lists of books, recent and historical, that oppose racist ideas, policies, and systems. What are we looking for in such lists? And can we really make good use of them? She makes a case for why fiction, poetry, and drama should not appear, since they deserve the status of art, not as instrumental works of social change. “It is unfair,” Jackson writes, “to beg other literature and other authors, many of them dead, to do this sort of work for someone,” when the work they set out to do is primarily creative. Ignoring genre “reinforces an already pernicious literary divide that books written by or about minorities are for educational purposes” only.

Despite many potential blind spots, despite the fact that “our customarily wan attention spans have been decimated” by pandemic and protest, the reading “has to get done,” Jackson wearily admits. Anti-racist booklists must circulate. And readers must make critical judgments about which books to read and what to take away from them, since we’re given the equivalent of a syllabus without a class or an instructor. We trust that our readers can find their way and will make a good faith effort to do the reading. There won’t be a graded exam; the test is far more consequential than that.

We solicited an anti-racist reading list on Twitter and chose the books below submitted by our readers. Since there’s no such thing as a definitive list, and different kinds of readers have different needs, we include other collections of readings lists here, including “41 Children’s Books to Support Conversations on Race, Racism, and Resistance.” You’ll find an anti-racist reading list on Twitter, here, compiled by doctoral researcher Victoria Alexander, and a list on LinkedIn entitled “Why White People Stay Silent on Racism, and What to Read First,” from organizational psychologist Adam Grant.

If this is overwhelming but you feel you must start to engage with the history and theory of anti-racism, don’t despair or buy a pile of books you know you can’t read right now. All of the most prominent anti-racist authors have been in high demand for interviews. “There are snappier places to glean the long-story-short of America, like podcasts, if it took someone this long to care,” writes Jackson, or if, like so many millions of other stressed out, angry, grieving, out-of-work Americans, you’re simply too burned out to crack another book. But if you’re willing and able to dig in, see our reader-submitted list below and suggest other titles you’d recommend in the comments. If you prefer audiobooks, many of these texts also exist as audiobooks on Audible. Get details on Audible’s free trial here.

Between the World and Me—Ta-Nehisi Coates: Hailed by Toni Morrison as “required reading,” a bold and personal literary exploration of America’s racial history by “the most important essayist in a generation and a writer who changed the national political conversation about race” (Rolling Stone)

Biased: Uncovering the Hidden Prejudice That Shapes What We See, Think, and Do—Jennifer L. Eberhardt PhD: How do we talk about bias? How do we address racial disparities and inequities? What role do our institutions play in creating, maintaining, and magnifying those inequities? What role do we play? With a perspective that is at once scientific, investigative, and informed by personal experience, Dr. Jennifer Eberhardt offers us the language and courage we need to face one of the biggest and most troubling issues of our time. She exposes racial bias at all levels of society—in our neighborhoods, schools, workplaces, and criminal justice system. Yet she also offers us tools to address it.

Black Like Me—John Howard Griffin: The history-making classic about crossing the line in America’s segregated south. The Atlanta Journal & Constitution calls it “One of the deepest, most penetrating documents yet set down on the racial question.”

How To Be An Antiracist — Ibram X. Kendi: “What do you do after you have written Stamped From the Beginning, an award-winning history of racist ideas? … If you’re Ibram X. Kendi, you craft another stunner of a book.… What emerges from these insights is the most courageous book to date on the problem of race in the Western mind, a confessional of self-examination that may, in fact, be our best chance to free ourselves from our national nightmare.”—The New York Times

I Can’t Breathe: A Killing on Bay Street—Matt Tiabbi: A work of riveting literary journalism that explores the roots and repercussions of the infamous killing of Eric Garner by the New York City police.

Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption—Bryan Stevenson: “Every bit as moving as To Kill a Mockingbird, and in some ways more so … a searing indictment of American criminal justice and a stirring testament to the salvation that fighting for the vulnerable sometimes yields.”—David Cole, The New York Review of Books

On the Courthouse Lawn: Confronting the Legacy of Lynching in the Twenty-First Century—Sherrilyn A. Ifill: “This pathbreaking book by Sherrilyn Ifill shows how the ugliest messages from our racial history and politics can hide openly in the public square. Her unflinching memory restores hope for the common good.”—Taylor Branch, Pulitzer Prize–winning author of Parting the Waters

So You Want to Talk About Race—Ijeoma Oluo: “Ijeoma Oluo’s [book] is a welcome gift to us all — a critical offering during a moment when the hard work of social transformation is hampered by the inability of anyone who benefits from systemic racism to reckon with its costs. Oluo’s mandate is clear and powerful: change will not come unless we are brave enough to name and remove the many forces at work strangling freedom. Racial supremacy is but one of those forces.” ―Darnell L. Moore, author of No Ashes in the Fire

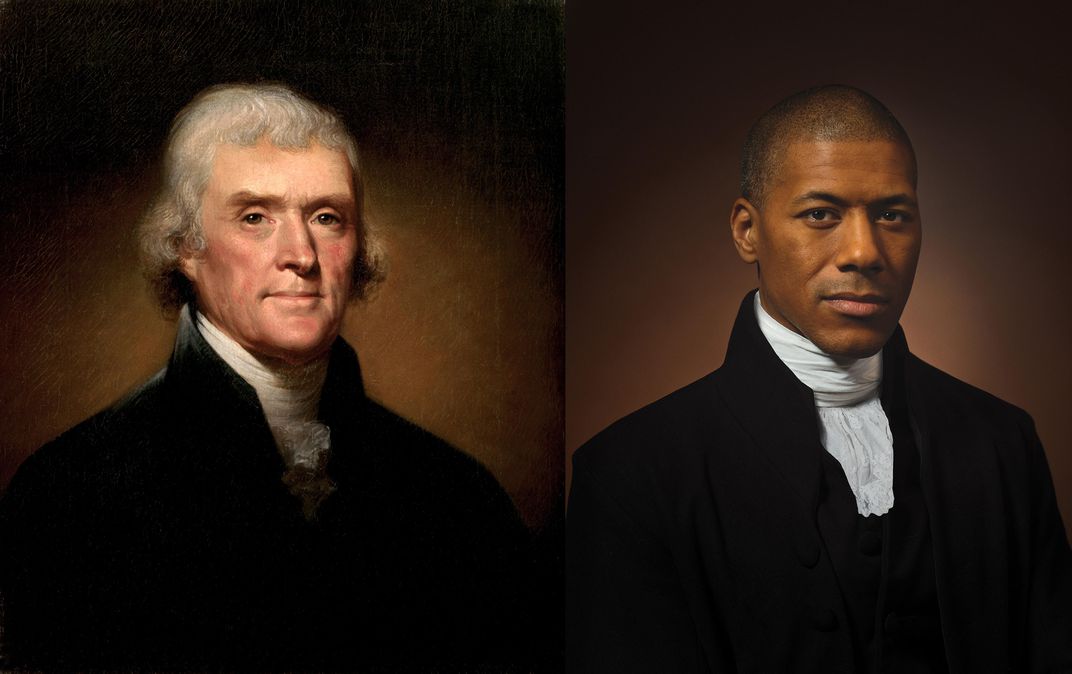

Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America—Ibram X. Kendi: The National Book Award winning history of how racist ideas were created, spread, and deeply rooted in American society. In this deeply researched and fast-moving narrative, Kendi chronicles the entire story of anti-black racist ideas and their staggering power over the course of American history. He uses the life stories of five major American intellectuals to drive this history: Puritan minister Cotton Mather, Thomas Jefferson, abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, W.E.B. Du Bois, and legendary activist Angela Davis.

Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You—Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi: “Readers who want to truly understand how deeply embedded racism is in the very fabric of the U.S., its history, and its systems will come away educated and enlightened. Worthy of inclusion in every home and in curricula and libraries everywhere. Impressive and much needed.” ―Kirkus

Sundown Towns—James Loewen: In this groundbreaking work, sociologist James W. Loewen brings to light decades of hidden racial exclusion in America. In a sweeping analysis of American residential patterns, Loewen uncovers the thousands of “sundown towns”—almost exclusively white towns where it was an unspoken rule that blacks weren’t welcome—that cropped up throughout the twentieth century, most of them located outside of the South.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X: As Told to Alex Haley: In the searing pages of this classic 1964 autobiography, Malcolm X outlines the lies and limitations of the American Dream, along with the inherent racism in a society that denies its nonwhite citizens the opportunity to dream.

The Color of Law—Richard Rothstein: Rothstein argues with exacting precision and fascinating insight how segregation in America—the incessant kind that continues to dog our major cities and has contributed to so much recent social strife—is the byproduct of explicit government policies at the local, state, and federal levels.

The Fire Next Time—James Baldwin: “Baldwin’s bestseller from 1963, which commemorated the centennial of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, still resonates powerfully today. The late author’s book consists of two essays that examine racial injustice in America, including his own experience growing up as a black teenager in Harlem.”

The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness —Michelle Alexander: The New Jim Crow “took the academy and the streets by storm, and forced the nation to reconsider the systems that allowed for blatant discrimination.”—The Chronicle of Higher Education

The Other by Wes Moore: “This is a fascinating book about two young men from Baltimore with the same name. One, the author, became a Rhodes Scholar while the other landed in jail. It’s as much a meditation on circumstance and luck as it is a commentary on how successful our society is in managing those who are on the precipice, both socially and economically.”

The Person You Mean to Be: How Good People Fight Bias—Dolly Chugh: An inspiring guide from Dolly Chugh, an award-winning social psychologist at the New York University Stern School of Business, on how to confront difficult issues including sexism, racism, inequality, and injustice so that you can make the world (and yourself) better.

The Warmth of Other Suns—Isabel Wilkerson: In this epic, beautifully written masterwork, Pulitzer Prize–winning author Isabel Wilkerson chronicles one of the great untold stories of American history: the decades-long migration of black citizens who fled the South for northern and western cities, in search of a better life.

White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism—Robin DiAngelo: The New York Times best-selling book exploring the counterproductive reactions white people have when their assumptions about race are challenged, and how these reactions maintain racial inequality.

White Rage—Carol Anderson: “White Rage is a riveting and disturbing history that begins with Reconstruction and lays bare the efforts of whites in the South and North alike to prevent emancipated black people from achieving economic independence, civil and political rights, personal safety, and economic opportunity.” — The Nation

Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?—Beverly Daniel Tatum: Walk into any racially mixed high school and you will see Black, White, and Latino youth clustered in their own groups. Is this self-segregation a problem to address or a coping strategy? Beverly Daniel Tatum, a renowned authority on the psychology of racism, argues that straight talk about our racial identities is essential if we are serious about enabling communication across racial and ethnic divides. This fully revised edition is essential reading for anyone seeking to understand the dynamics of race in America.

Related Content:

Noam Chomsky Explains the Best Way for Ordinary People to Make Change in the World, Even When It Seems Daunting

Watch Ava DuVernay’s 13th Free Online: An Award-Winning Documentary Revealing the Inequalities in the US Criminal Justice System

Albert Einstein Explains How Slavery Has Crippled Everyone’s Ability to Think Clearly About Racism

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness