How to make a life-sized facsimile of a human skeleton:

- Download files published under a Creative Commons license, and arrange to have them 3‑D printed.

or

- Do as artist Shanell Papp did, above, and crochet one.

The latter will take considerably more time and attention on your part. Papp gave up all extracurricular activities for four months to hook the woolen skeleton around her work and school schedule. Equipping it with internal organs ate up another four.

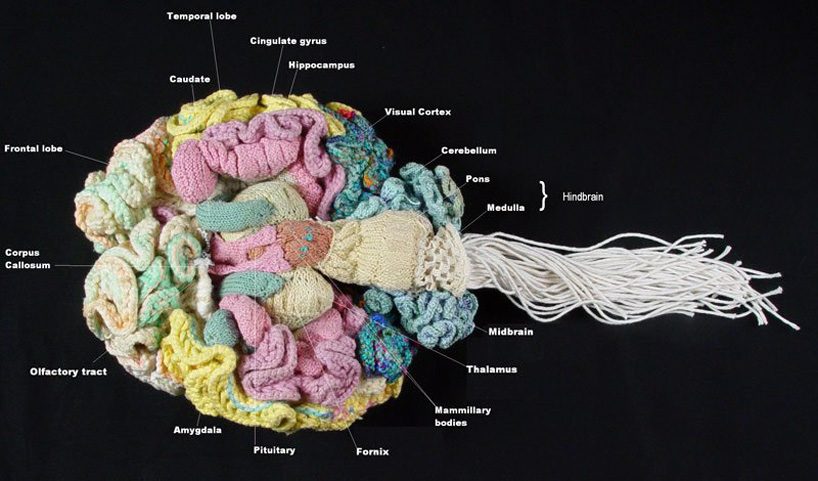

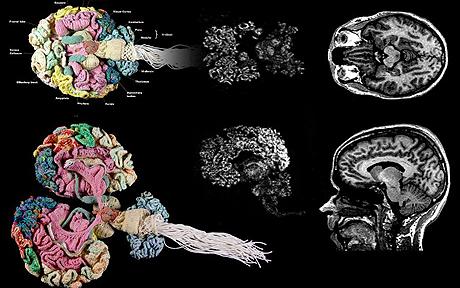

To ensure accuracy, Papp armed herself with anatomical textbooks and an actual human skeleton on loan from the University of Lethbridge, where she was an undergrad. The brain has gray and white matter, there’s marrow in the bones, the stomach contains half-digested wool food, and the intestines can be unspooled to a realistic length.

The grueling 2006 project did not exhaust her fascination for the intricacies of human anatomy. The University of Saskatchewan granted her open access to draw in the gross anatomy lab while she pursued her MFA.

As she told MICE magazine:

I wanted this work to illustrate all of the organs and bones everyone shares and to not highlight differences. Much of anatomical history is about defining difference, by comparative analysis. This can set up strange taxonomies and hierarchies. I wasn’t interested in participating in that; I wanted to expose the fragile, common, and unseen things in all of us.

The finished piece, which is displayed supine on a gurney she nabbed for free during a mortuary renovation, incorporates many of Papp’s other abiding interests: horror, medical history, Frankenstein, crime investigation, and mortuary practices.

Papp, who taught herself how to crochet from books as a child, using whatever yarn found its way to her grandma’s junk shop, appreciates how her chosen medium adds a layer of homey softness and familiarity to the macabre.

It’s also not lost on her that fiber arts, often dismissed as too “crafty” by the establishment, were an important component of 70s-era feminist art, though in her view, her work is more of a statement on the history of textile manufacturing, which is to say the history of labor and class struggle.

See more of Shanell Papp’s work here.

All images in this post by Shanell Papp.

Related Content:

Behold an Anatomically Correct Replica of the Human Brain, Knitted by a Psychiatrist

The Beautiful Math of Coral & Crochet

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inkyzine. Join her in NYC on Monday, September 9 for another season of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday.