Image via Wikimedia Commons

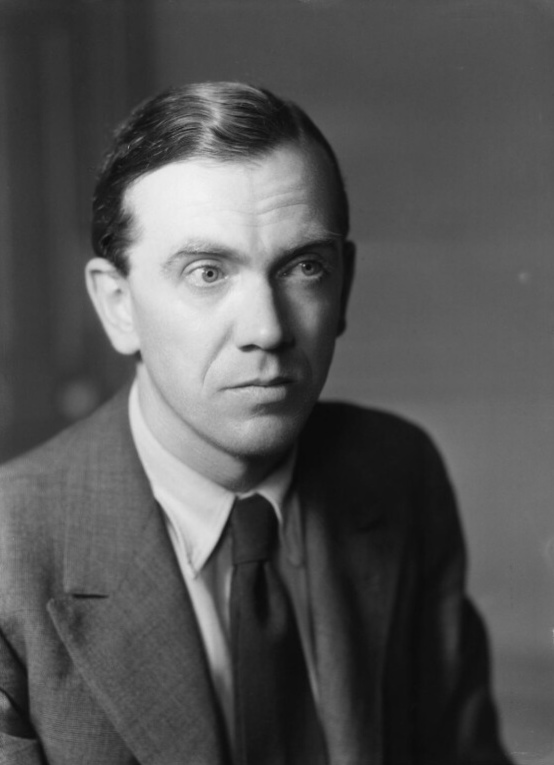

Nobody can write a book. That is, nobody can write a book at a stroke — unless aided by aggressively mind-invigorating substances, and even then they seldom pull it off. As professional writers know all too well, composing just one passable chapter at a sitting demands a Stakhanovite fortitude (or more commonly, a threateningly close deadline). Books are written less one chapter at a time than one section at a time, less one section at a time than one paragraph at a time, less one paragraph at a time than one sentence at a time, and less one sentence at a time than one word at a time. Graham Greene wrote his formidable body of work, more than 50 books, including novels, poetry and short fiction collections, memoirs, and children’s stories, 500 words at a time.

In one of his most beloved novels, 1951’s The End of the Affair, Greene has his writer protagonist Maurice Bendrix describe a working method much like his own:

Over twenty years I have probably averaged five hundred words a day for five days a week. I can produce a novel in a year, and that allows time for revision and the correction of the typescript. I have always been very methodical, and when my quota of work is done I break off, even in the middle of a scene. Every now and then during the morning’s work I count what I have done and mark off the hundreds on my manuscript. No printer need make a careful cast-off of my work, for there on the front page is marked the figure — 83,764.

In his youth, Bendrix notes, “not even a love affair would alter my schedule,” nor could one interrupt the nightly phase of his process: “However late I might be in getting to bed — as long as I slept in my own bed — I would read the morning’s work over and sleep on it.”

Much of a novelist’s writing, he believes, “takes place in the unconscious; in those depths the last word is written before the first word appears on paper. We remember the details of our story, we do not invent them.” Greene, too, set enough store by the unconscious to keep a dream journal. A few year after The End of the Affair, writesThe New Yorker’s Maria Konnikova, “he faced a creative ‘blockage,’ as he called it, that prevented him from seeing the development of a story or even, at times, its start. The dream journal proved to be his savior.”

All of us who write, whatever we write, can learn from Greene’s methods; Michael Korda got to witness them first-hand. In the summer of 1950 he was invited by his uncle, the film producer Alexander Korda, to come along on a French-Riviera cruise with a variety of major industry figures, Greene included. By that point Greene had already written a fair few screenplays, including adaptations of his own novels Brighton Rock and The Third Man. But each morning on the yacht he worked on a more personal project, as the sixteen-year-old Korda watched:

An early riser, he appeared on deck at first light, found a seat in the shade of an awning, and took from his pocket a small black leather notebook and a black fountain pen, the top of which he unscrewed carefully. Slowly, word by word, without crossing out anything, and in neat, square handwriting, the letters so tiny and cramped that it looked as if he were attempting to write the Lord’s Prayer on the head of a pin, Graham wrote, over the next hour or so, exactly five hundred words. He counted each word according to some arcane system of his own, and then screwed the cap back onto his pen, stood up and stretched, and, turning to me, said, “That’s it, then. Shall we have breakfast?” I did not, of course, know that he was completing The End of the Affair.

This working ritual, a Korda describes it, suits the sensibilities of the writer, a convert to Catholicism who dealt with themes of religious practice in his work:

Greene’s self-discipline was such that, no matter what, he always stopped at five hundred words, even if it left him in the middle of a sentence. It was as if he brought to writing the precision of a watchmaker, or perhaps it was that in a life full of moral uncertainties and confusion he simply needed one area in which the rules, even if self-imposed, were absolute. Whatever else was going on, his daily writing, like a religious devotion, was sacred and complete. Once the daily penance of five hundred words was achieved, he put the notebook away and didn’t think about it again until the next morning.

Just as Greene’s adherence to Catholicism lost some of its rigor in his later years (he claimed to have been converted by arguments, then forgotten the arguments), his daily word count decreased. “In the old days, at the beginning of a book, I’d set myself 500 words a day, but now I’d put the mark to about 300 words,” a 66-year-old Greene told the New York Times in 1971. But such are the wages of the novelist’s art, in which Greene felt a demand to “know — even if I’m not writing it — where my character’s sitting, what his movements are. It’s this focusing, even though it’s not focusing on the page, that strains my eyes, as though I were watching something too close.”

Greene wasn’t alone in writing a certain number of words each day. According to a post at Word Counter, Ernest Hemingway got started on his own 500 daily words at first light. Ian McEwan says he aims “for about six hundred words a day and hope for at least a thousand when I’m on a roll.” For the more prolific J.G. Ballard, a thousand was the minimum, “even if I’ve got a hangover. You’ve got to discipline yourself if you’re professional. There’s no other way.” The near-inhumanly prolific Stephen King doubles that: “I like to get ten pages a day, which amounts to 2,000 words,” he says in his memoir On Writing. “On some days those ten pages come easily; I’m up and out and doing errands by eleven-thirty in the morning, perky as a rat in liverwurst. More frequently, as I grow older, I find myself eating lunch at my desk and finishing the day’s work around one-thirty in the afternoon.”

John Updike, no slouch when it came to productivity, recommended writing for a length of time rather than to a number of words. “Even though you have a busy life, try to reserve an hour, say — or more — a day to write,” he says in an interview clip previously featured here on Open Culture. “Some very good things have been written on an hour a day.” At The Guardian, novelist Neil Griffiths discusses his apostasy from the thousand-words-a-day method: “I’m writing a novel — an artistic enterprise, one hopes — but I was measuring my working day by a number.” Switching to the “finish the bit you’re working on” method, he writes, means he doesn’t have “half an eye on what is going to happen in the next bit because without it I’ll never make the day’s 1000. My sole concern is the words before me, however many or few they are, and getting them right before moving on.” And so, it seems, those of us trying to get our life’s work written have two options: do what Graham Greene did, or do the opposite.

Related Content:

John Updike’s Advice to Young Writers: ‘Reserve an Hour a Day’

Ursula K. Le Guin’s Daily Routine: The Discipline That Fueled Her Imagination

The Daily Routines of Famous Creative People, Presented in an Interactive Infographic

Stephen King’s 20 Rules for Writers

The Seven Road-Tested Habits of Effective Artists

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.