Wet cement triggers a primal impulse, particularly in children.

It’s so tempting to inscribe a pristine patch of sidewalk with a lasting impression of one’s existence.

Is the coast clear? Yes? Quick, grab a stick and write your name!

No stick?

Sink a hand or foot in, like a movie star…

…or, even more thrillingly, a child hominin on the High Tibetan Plateau, 169,000 to 226,000 years ago!

Perhaps one day your surface-marring gesture will be conceived of as a great gift to science, and possibly art. (Try this line of reasoning with the angry homeowner or shopkeeper who’s intent on measuring your hand against the one now permanently set into their new cement walkway.)

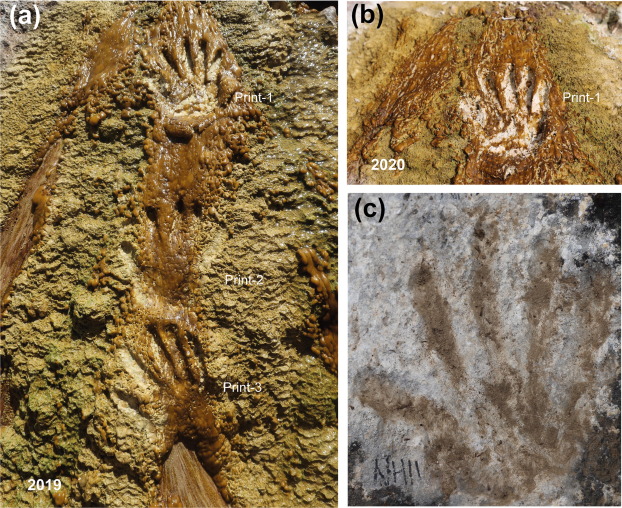

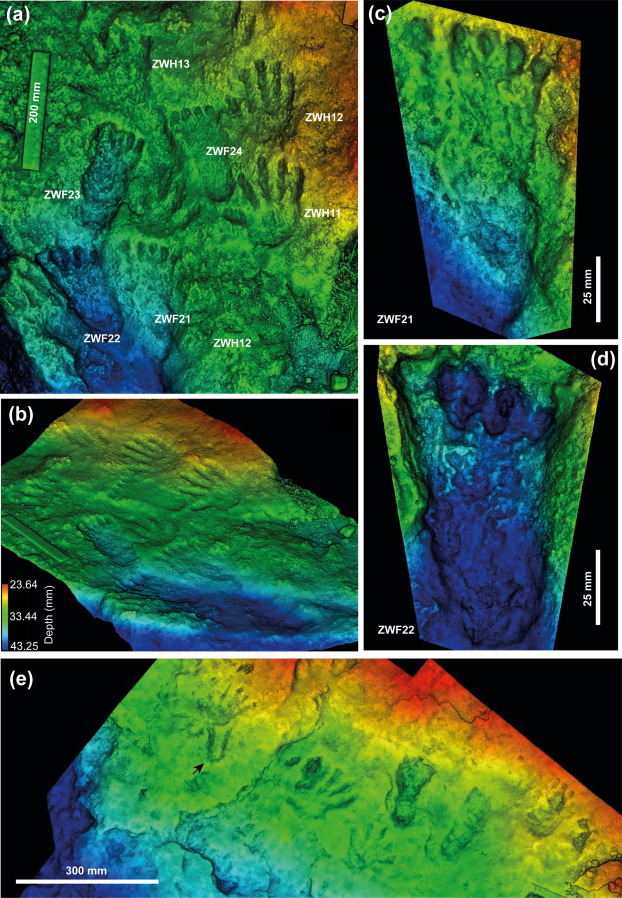

Tell them how in 2018, professional ichnologists doing fieldwork in Quesang Hot Spring, some 80 km northwest of Lhasa, were over the moon to find five handprints and five footprints dating to the Middle Pleistocene near the base of a rocky promontory.

Researchers led by David Zhang of Guangzhou University attribute the handprints to a 12-year-old, and the footprints to a 7‑year-old.

In a recent article in Science Bulletin, Zhang and his team conclude that the children’s handiwork is not only deliberate (as opposed to “imprinted during normal locomotion or by the use of hands to stabilize motion”) but also “an early act of parietal art.”

The Uranium dating of the travertine which received the kids’ hands and feet while still soft is grounds for excitement, moving the dial on the earliest known occupation (or visitation) of the Tibetan Plateau much further back than previously believed — from 90,000–120,000 years ago to 169,000–226,000 years ago.

That’s a lot of food for thought, evolutionarily speaking. As Zhang told TIME magazine, “you’re simultaneously dealing with a harsh environment, less oxygen, and at the same time, creating this.”

Zhang is steadfast that “this” is the world’s oldest parietal art — outpacing a Neanderthal artist’s red-pigmented hand stencil in Spain’s Cave of Maltravieso by more than 100,000 years.

Other scientists are not so sure.

Anthropologist Paul Taçon, director of Griffith University’s Place, Evolution and Rock Art Heritage Unit, thinks it’s too big of “a stretch” to describe the impressions as art, suggesting that they could be chalked up to a range of activities.

Nick Barton, Professor of Paleolithic Archeology at Oxford wonders if the traces, intentionally placed though they may be, are less art than child’s play. (Team Wet Cement!)

Zhang counters that such arguments are predicated on modern notions of what constitutes art, driving his point home with an appropriately stone-aged metaphor:

When you use stone tools to dig something in the present day, we cannot say that that is technology. But if ancient people use that, that’s technology.

Cornell University’s Thomas Urban, who co-authored the Science Bulletin article with Zhang and a host of other researchers shares his colleagues aversion’ to definitions shaped by a modern lens:

Different camps have specific definitions of art that prioritize various criteria, but I would like to transcend that and say there can be limitations imposed by these strict categories that might inhibit us from thinking more broadly about creative behavior. I think we can make a solid case that this is not utilitarian behavior. There’s something playful, creative, possibly symbolic about this. This gets at a very fundamental question of what it actually means to be human.

Related Content:

1,700 Free Online Courses from Top UniversitiesWas a 32,000-Year-Old Cave Painting the Earliest Form of Cinema?

Hear a Prehistoric Conch Shell Musical Instrument Played for the First Time in 18,000 Years

40,000-Year-Old Symbols Found in Caves Worldwide May Be the Earliest Written Language

Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primaologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.