Though he became known for the physical comedy of characters like the irate owner of a dead parrot, a minister of silly walks, and the always buffoonish Basil Fawlty, John Cleese is actually a very deep thinker. This will probably come as no surprise to fans of Monty Python’s intellectual humor, but it’s still a treat to see him, out of character, getting serious about ideas, even if he can’t resist the odd joke or ten. His subject? Creativity. His forum? Well, in the video above, we see Cleese at the 2009 World Creativity Forum in Germany. In a 2010 guest post on this talk, Maria Popova of Brain Pickings called the event “part critique of modernity’s hustle-and-bustle, part handbook for creating the right conditions for creativity.” What does John Cleese have to say about creating those conditions?

By combining another talk from Cleese from 1991 (below), we are able to piece together a Cleese philosophy of creativity. He begins in his ’91 talk by telling people what creativity is not, and why lecturing on it is “a complete waste of time.” The reason? It cannot be explained. “It is literally inexplicable.”

Drawing on research from his friend Brian Bates, a psychologist as Sussex University, Cleese claims that those considered more creative do not differ in any significant way from their equally intelligent and talented peers, and therefore, they do not possess any special skills or abilities that would qualify as “creativity.” As a onetime student of the sciences at Cambridge, Cleese has a high regard for data and observation, and in each of these talks, he applies a scientific method to his subject.

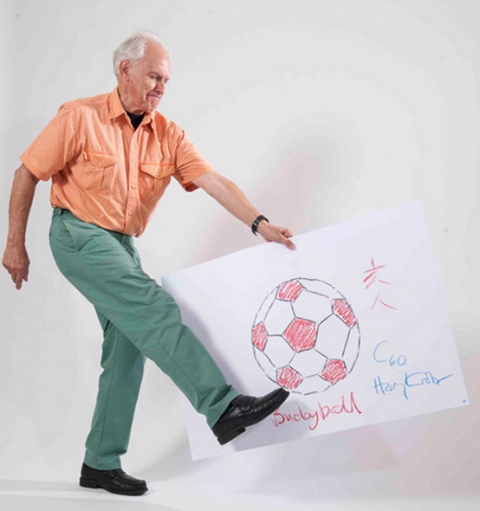

What, then, has he learned from observing his own work habits and looking at the research? What can he positively say about creativity? For one thing, it is not a skill or an aptitude, it is a “mood,” one Cleese describes as “childlike” in that it aids one in the ability to play. Cleese makes a similar point in his 2009 talk at the top, emphasizing that acquiring this mood is difficult but not impossible. As all artists know, genuine creative insights occur when rational thought ceases—during dreamstates or moments of absorption so intense that self-consciousness, anxiety, and the needling cares of the day drop away. As Cleese put it at the World Creativity Forum, “if you’re racing around all day, ticking things off a list, looking at your watch, making phone calls and generally just keeping all the balls in the air, you are not going to have any creative ideas.” This explains why the offices of companies like Google are full of toys, why the workdays of the Mad Men “creatives” often resemble preschool, and why artists’ work spaces tend to be so intriguing to peer into. They are, as Cleese terms them, “oases” from the punishing pace of the workaday world.

In Cleese’s considered opinion, such oases, both physical and mental, are the preconditions for childlike wonder to override adult routine ways of thinking. Of course as Cleese and his hard-working co-creators also show us, a great deal of grown-up discipline is required to bring creative ideas to fruition. The trick, Cleese says, is in making the space to engage in childlike play without relying on childish spontaneity—he recommends scheduling time to be creative, giving oneself a “starting time and a finish time” and thereby setting “boundaries of space, boundaries of time.” Of course, this kind of mindful structuring is something only a mature adult mind can do. Seeing this grown-up side of Cleese gives us a new appreciation for the consistently childlike characters he’s created over the years, and for the role of conscious attention in safeguarding and nurturing unconscious insight.

Related Content:

David Lynch Explains How Meditation Enhances Our Creativity

Malcolm McLaren: The Quest for Authentic Creativity

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness