C.D. Hermelin, a literary agency associate with a degree in Creative Writing, is the self-proclaimed Roving Typist. It’s an apt title for one who achieved fame and fortune — okay, rent money — by appearing in various public spaces around New York City, typewriter in lap. Director Mark Cersosimo’s short film, above, introduces him as a mild-mannered, slightly awkward soul. Engaging with strangers lured by the sign taped to his typewriter case is where Hermelin comes into his own.

The sign promises “stories while you wait,” a concept that recalls the “Poems on Demand” author and writing guru, Natalie Goldberg, who composed poems to raise funds for the Minnesota Zen Center. (Hermelin got his idea — and permission to implement it — from a guy he saw doing something similar in San Francisco.)

He’s open to requests, and payment is left to the discretion of the recipient. He seems to take extra care when his customer is a child.

A harmless enough pursuit in an era where subway musicians and caricaturists lining the path to the Central Park Zoo hustle harder than ‘90s-era shell game artistes.

It’s reasonable to assume that innocently blundering onto a cello player’s turf is the worst trouble a guy like Hermelin’s likely to stir up.

Instead, he became the target of a mass cyberbullying campaign, after a stranger posted a photo of him and his typewriter parked on the High Line on a sweltering day in 2012. Cue an avalanche of hipster-hating Reddit comments, in addition to a meme at his expense.

Rather than succumb to the vast negative outpouring, the Roving Typist confronted the situation head on, publishing his side of the story in The Awl:

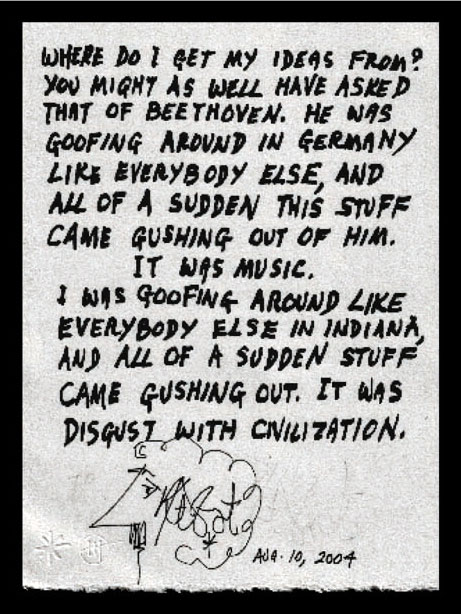

Originally, it felt silly labeling my venture a “cause” while I defended myself to an anonymous horde—but now it feels anything but. The experience of being labeled and then cast aside made me realize that what many people call “hipsterism” or, what they perceive as a slavish devotion to irony, are often in fact just forms of extreme, radical sincerity. I think of Brooklyn-based “hipster” brand Mast Brothers Chocolate, which uses an old-fashioned schooner to retrieve their cacao beans, because the energy is cleaner, because they think that’s how it should be done. I think of the legions of Etsy-type handmade artist shops, of people who couldn’t make money in their profession, so found a way to make money with their art.

Subject a whimsical project to the forge, and it just might become a vocation.

Be sure to check out the bonus outtake “I Was A Hated Hipster Meme” and don’t fret if your travels won’t take you near New York City anytime soon. Hermelin and his typewriter are spending the winter indoors, fulfilling the public’s on-demand stories via mail order.

Related Content:

David Rees Presents a Primer on the Artisanal Craft of Pencil Sharpening

Humans of New York: Street Photography as a Celebration of Life

What Happens When Everyday People Get a Chance to Conduct a World-Class Orchestra in NYC

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and Chief Primatologist of the long running zine, The East Village Inky. Follow her @AyunHalliday