Image by WikiArt, via Wikimedia Commons

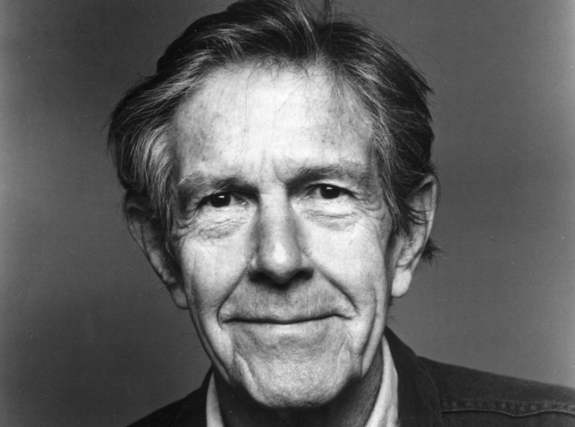

You know what they say: eighty percent of the work you do on a project, you do getting the last twenty percent of that project right. But most of that other twenty percent of the work must go toward getting started in the first place; you’ve got to get over a pretty big hill just to get to the point of writing the first sentence, painting the first stroke, shooting the first shot, or playing the first chords. Avant-garde composer John Cage knew well the challenges of just getting started, and his thoughts on the subject motivated him, toward the end of his career, to do the written, performed, and recorded project we feature today, How to Get Started.

Cage himself only put on How to Get Started once, at an international conference on sound design at George Lucas’ Skywalker Ranch on August 31, 1989. It worked like this: he brought with him ten note cards, each of which contained notes for a particular “idea” he wanted to talk about. On went a tape recorder, and he began speaking improvisationally about the first idea. Then he flipped to the next card, and as he talked about its idea, the recording of the first one played in the background. He continued with this procedure until, by the tenth idea on the tenth card, he had his impromptu speeches on all nine previous ideas playing simultaneously behind him. You can get an idea of what his readings sounded like in the three clips (from howtogetstarted.org) embedded here [first, second, third].

The ten ideas Cage jotted down on his notecards come inspired by, and inspired him to discuss further, his own creative experiences. In the first, he describes a new compositional process that came to him in a dream, which involves crumpling a score into a ball and unfolding it again. In the third, he thinks back to his work Roaratorio, an Irish circus on Finnegans Wake, which converted Joyce’s novel into music, and imagines a way forward that would involve turning into music not one book at a time but several. In the fifth, he references Marcel Duchamp’s “The Creative Act,” which brought home for him the notion of how audiences “finish the work by listening,” which led to his creating works of “musical sculpture,” including one particularly memorable example involving “between 150 and 200” Yugoslavian high school students, all playing their instruments in different places.

Cage’s other stories of creative epiphany in How to Get Started involve a trip to an anechoic chamber; finding out what made one dance performance at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts so “tawdry, shabby, miserable”; discovering the artist’s “inner clock” in Leningrad; and how he works around what no less a musical mind than Arnold Schoenberg diagnosed as his absent sense of harmony. You can read a transcript of all of them in a PDF of How to Get Started’s companion booklet. And depending upon how inspired you find yourself (or how close you live to Philadelphia), you might consider making the trip to the Slought Foundation, who have built a room specially designed for the piece. You might not come out of it feeling like you’ve absorbed all the creativity of John Cage, but he himself points us toward the important thing: not the amorphous quality of creativity, but the action of getting started.

Related Content:

The Universal Mind of Bill Evans: Advice on Learning to Play Jazz & The Creative Process

Isaac Asimov Explains the Origins of Good Ideas & Creativity in Never-Before-Published Essay

John Cleese’s Philosophy of Creativity: Creating Oases for Childlike Play

David Lynch Explains How Meditation Enhances Our Creativity

Jump Start Your Creative Process with Brian Eno’s “Oblique Strategies” Deck of Cards (1975)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.