We are a haunted species: haunted by the specter of climate change, of economic collapse, and of automation making our lives redundant. When Marx used the specter metaphor in his manifesto, he was ironically invoking Gothic tropes. But Communism was not a boogeyman. It was a coming reality, for a time at least. Likewise, we face very real and substantial coming realities. But in far too many instances, they are also manufactured, under ideologies that insist there is no alternative.

But let’s assume there are other ways to order our priorities, such as valuing human life as an end in itself. Perhaps then we could treat the threat of automation as a ghost: insubstantial, immaterial, maybe scary but harmless. Or treat it as an opportunity to order our lives the way we want. We could stop inventing bullshit, low-paying, wasteful jobs that contribute to cycles of poverty and environmental degradation. We could slash the number of hours we work and spend time with people and pursuits we love.

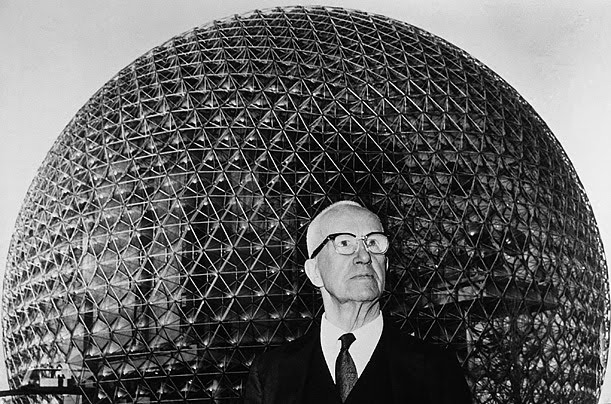

We have been taught to think of this scenario as a fantasy. Or, as Buckminster Fuller declared in 1970—on the threshold of the “Malthusian-Darwinian” wave of neoliberal thought to come—“We keep inventing jobs because of this false idea that everybody has to be employed at some kind of drudgery…. He must justify his right to exist.” In current parlance, every person must somehow “add value” to shareholders’ portfolios. The shareholders themselves are under no obligation to return the favor.

What about adding value to our own lives? “The true business of people,” says Fuller, “should be to go back to school and think about whatever it was they were thinking about before somebody came along and told them they had to earn a living.” Against the “specious notion” that everyone should have to make a wage to live–this “nonsense of earning a living”–he takes a more magnanimous view: “It is a fact today that one in ten thousand of us can make a technological breakthrough capable of supporting all the rest,” who then may go on to make millions of small breakthroughs of their own.

He may have sounded overconfident at the time. But fifty years later, we see engineers, developers, and analysts of all kinds proclaiming the coming age of automation in our lifetimes, with a majority of jobs to be fully or partially automated in 10–15 years. It is a technological breakthrough capable of dispensing with huge numbers of people, unless its benefits are widely shared. The corporate world sticks its head in the sand and issues guidelines for retraining, a solution that will still leave masses unemployed. No matter the state of the most recent jobs report, serious losses in nearly every sector, especially manufacturing and service work, are unavoidable.

The jobs we invent have changed since Fuller’s time, become more contingent and less secure. But the obsession with creating them, no matter their impact or intent, has only grown, a runaway delusion no one can seem to stop. Should we fear automation? Only if we collectively decide the current course of action is all there is, that “everybody has to earn a living”—meaning turn a profit—or drop dead. As Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez—echoing Fuller—put it recently at SXSW, “we live in a society where if you don’t have a job, you are left to die. And that is, at its core, our problem…. We should not be haunted by the specter of being automated out of work.”

“We should be excited about automation,” she went on, “because what it could potentially mean is more time to educate ourselves, more time creating art, more time investing in and investigating the sciences.” However that might be achieved, through subsidized health, education, and basic services, new New Deal and Civil Rights policies, a Universal Basic Income, or some creative synthesis of all of the above, it will not produce a utopia—no political solution is up that task. But considering the benefits of subsidizing our humanity, and the alternative of letting its value decline, it seems worth a shot to try what economist Bill Black calls the “progressive policy core,” which, coincidentally, happens to be “centrist in terms of the electorate’s preferences.”

Related Content:

Bertrand Russell & Buckminster Fuller on Why We Should Work Less, and Live & Learn More

The Life & Times of Buckminster Fuller’s Geodesic Dome: A Documentary

Everything I Know: 42 Hours of Buckminster Fuller’s Visionary Lectures Free Online (1975)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness