However you feel about electronic music, you’ll still find yourself listening to it most places you go. For better or worse, it has become mood music, soothing the jangled nerves of customers in coffee shops and lulling boutique shoppers into a pleasant sense of hip. Some computer music pioneers have moved on from composing their own music to making computers do it for them. It’s precisely the kind of thing I imagine Alan Turing might have pursued had the computer science giant also been a musician.

In fact, Turing did inadvertently create a computer that could play music when he input a sequence of instructions into it, which relayed sound to a loudspeaker Turing called “the hooter.” By varying the “hoot” commands, Turing found that he could make the hooter produce different notes, but he was “not very interested in programming the computer to play conventional pieces of music,” note Jack Copeland and Jason Long at the British Library’s Sound and Vision blog. Turing “used the different notes” as a rudimentary notification system, “to indicate what was going on in the computer.”

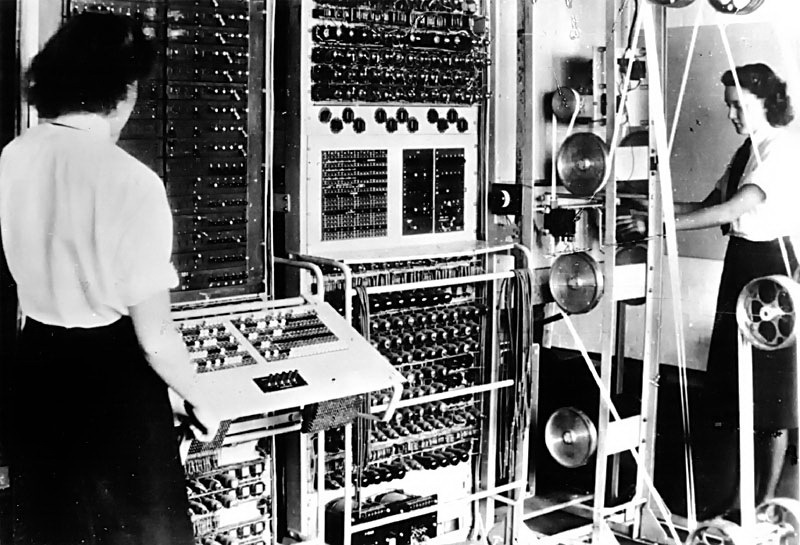

Instead, the task fell to schoolteacher, pianist, and future computer scientist Christopher Strachey to create the first computer-generated music, using Turing’s gigantic Mark II, its programming manual, and “the longest computer program ever to be attempted.” After an all-night session, Strachey had taught the computer to hoot out “God Save the Queen.” Upon hearing the composition the next morning, Turing exclaimed, “good show,” and Strachey received a job offer just a few weeks later.

Once the BBC heard of the achievement, they visited Turing’s Computing Machine Laboratory and made the recordings above in 1951, which include a version of Strachey’s “God Save the Queen” program and renditions of “Baa Baa Black Sheep” and Glenn Miller’s “In the Mood.” The “original 12-inch disc the melodies were recorded on,” writes The Verge, “has been known about for a while, but when Copeland (a professor) and Long (a composer) listened to it, they found the audio was not accurate.” The two describe in their blog post how they went about restoring the audio and how it came to exist in the first place.

While the music Turing’s computer produced sounds painfully primitive, it would be several more years before composers began to really experiment with computer-generated music beyond the rudimentary first steps, and well over a decade before the design of systems that could operate in real time.

Now, although they still require human input (“the singularity isn’t upon us,” writes Spin), computers have begun to compose their own music, like “Daddy’s Car,” a Beatles-esque song generated by a SONY CSL Research Laboratory AI called Flow Machine. Here, a composer mixes and matches different elements, a style, melody, lyrics, etc. from various databases. The machine produces the sounds. SONY labs have been generating computer-made jazz and classical music for some time now—some of which we may have already heard as background music.

As Spin points out, already a new startup called Jukedeck promises to “generate a song in the genre and mood of your choosing…” perhaps as “background music for advertisements or YouTube vlogs.” True to the spirit of the man who inadvertently invented computer music, and who theorized how a computer might demonstrate consciousness, the software will ask you to confirm that you are not a robot.

via The Verge

Related Content:

The Enigma Machine: How Alan Turing Helped Break the Unbreakable Nazi Code

The History of Electronic Music, 1800–2015: Free Web Project Catalogues the Theremin, Fairlight & Other Instruments That Revolutionized Music

Pioneering Electronic Composer Karlheinz Stockhausen Presents “Four Criteria of Electronic Music” & Other Lectures in English (1972)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness