Ancient Greece and Rome have provided fertile hunting grounds for animated subject matter since the very inception of the form.

So what if the results wind up doing little more than frolic in the pastoral setting? Witness 1930’s Playful Pan, above, which can basically be summed up as Silly Symphony in a toga (with a cute bear cub who looks a lot like Mickey Mouse and some flame play that prefigures The Sorcerer’s Apprentice…)

Others are packed with history, mythic narrative, and period details, though be forewarned that not all are as visually appealing as Steve Simons’ Hoplites! Greeks at War, part of the Panoply Vase Animation Project.

Some series, such as the Asterix movies and Aesop and Son—a staple of The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show from 1959 to 1962—have been the gateways through which many history lovers’ curiosity was first roused.

(Russian animator Anatoly Petrov’s erotic shorts for Soyuzmultfilm may rouse other, er, curiosities, and are definitely NSFW.)

And then there are instant classics like 2004’s It’s All Greek to Scooby in which “Shaggy’s purchase of a mysterious amulet only serves to cause a pestering archaeologist and centaur to chase him.” (Ye gods…)

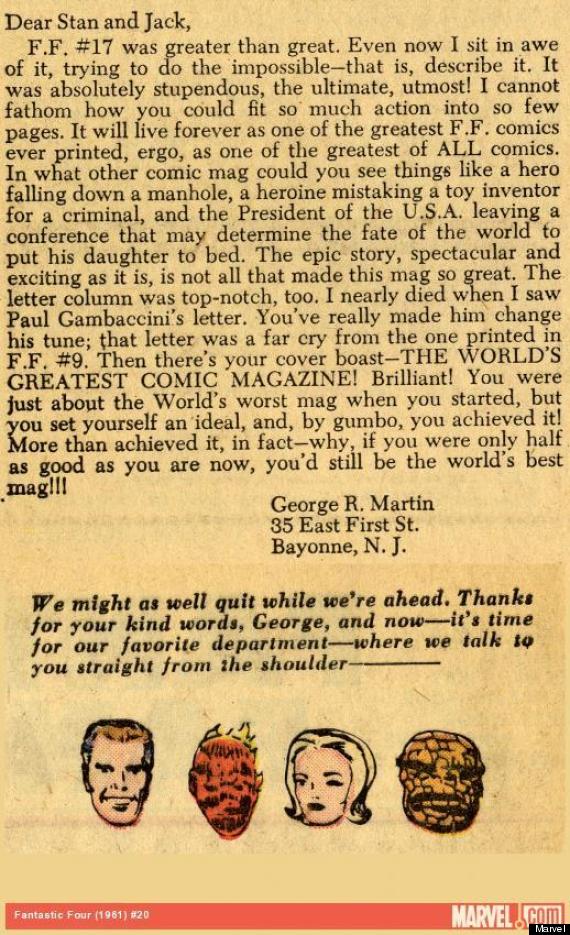

Senior Lecturer of Classical and Mediterranean Studies at Vanderbilt, Chiara Sulprizio, has collected all of these and more on her blog, Animated Antiquity.

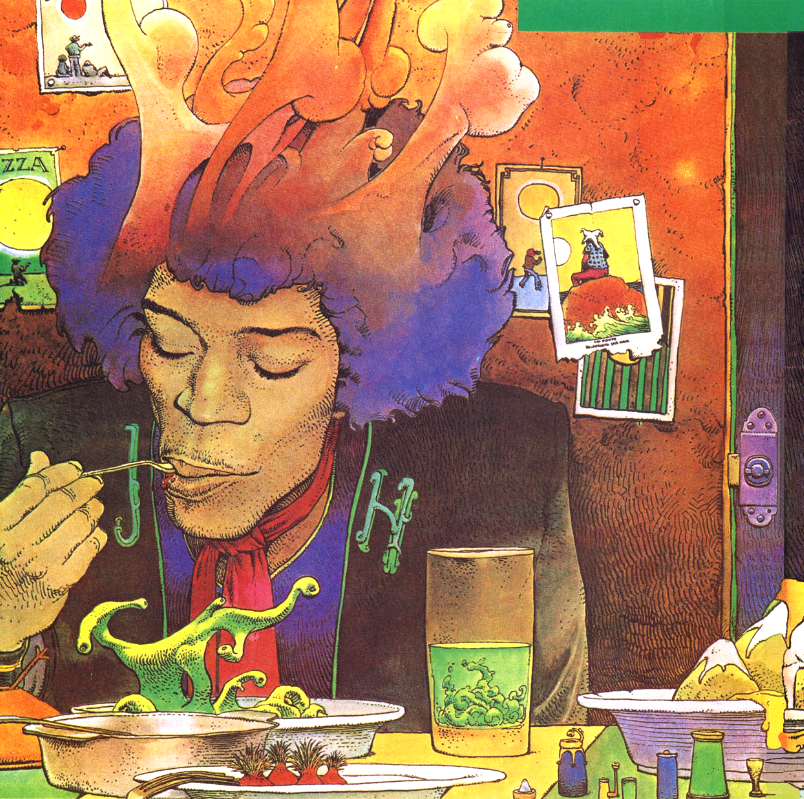

Beginning with the 2‑minute fragment that’s all we have left of Winsor McCay’s 1921 The Centaurs, Sulprizio shares some of her favorite cartoon representations of ancient Greece, Rome, and beyond. Her areas of professional specialization—gender and sexuality, Greek comedy, and Roman satire—are well suited to her chosen hobby, and her commentary doubles down on historical context to include the history of animation.

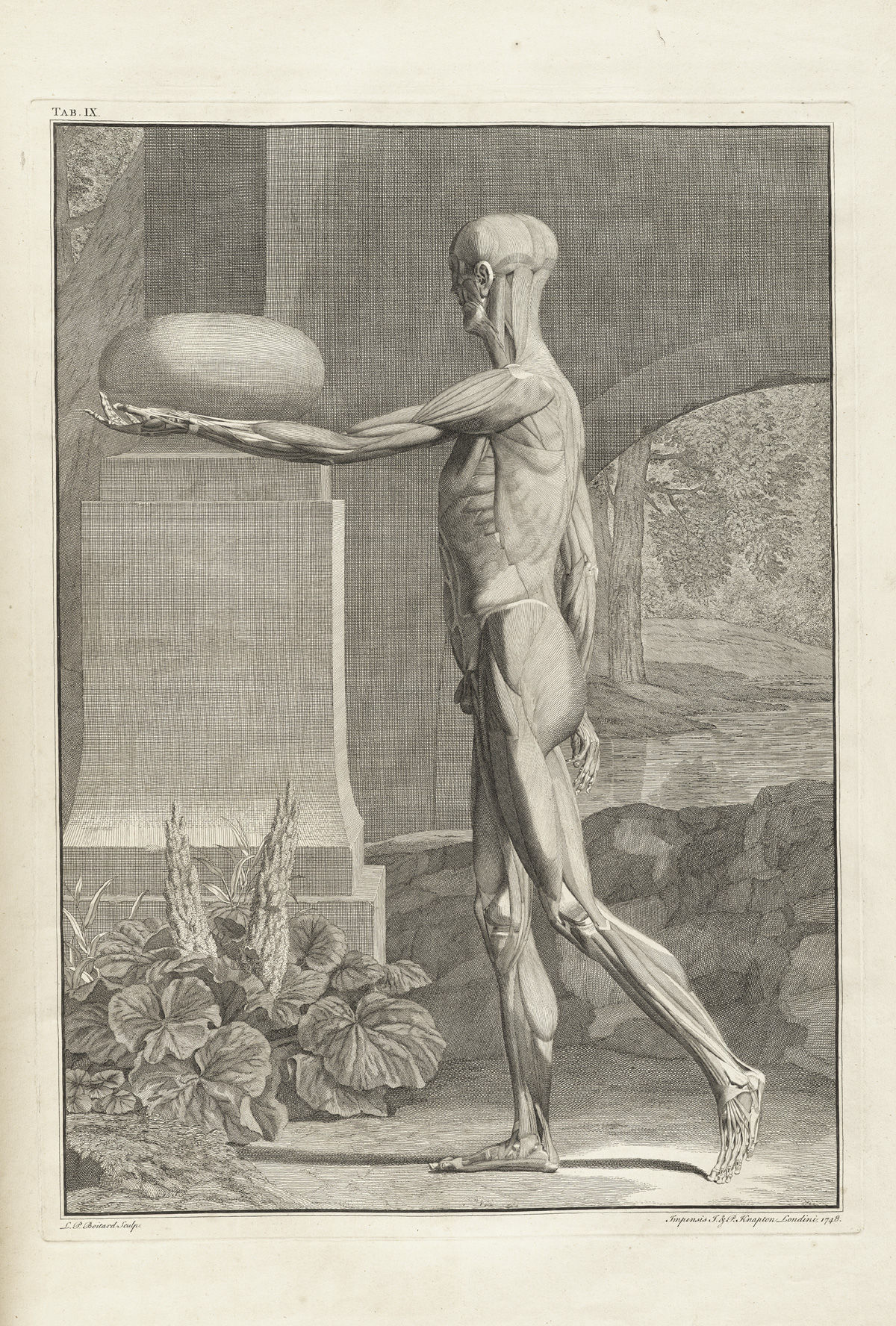

The appearance of cartoon stars like Daffy Duck, Tom and Jerry, and Popeye further demonstrates this antique subject matter’s sturdiness. TED-Ed and the BBC may view the genre as an excellent teaching tool, but there’s nothing stopping the animator from shoehorning some fabrications in amongst the buxom nymphs and buff gladiators.

(Raise your hand if your mother ever sacrificed you on the altar to Spinachia, goddess of spinach, in hopes that she might unleash a mushroom cloud of super-atomic power in your puny bicep.)

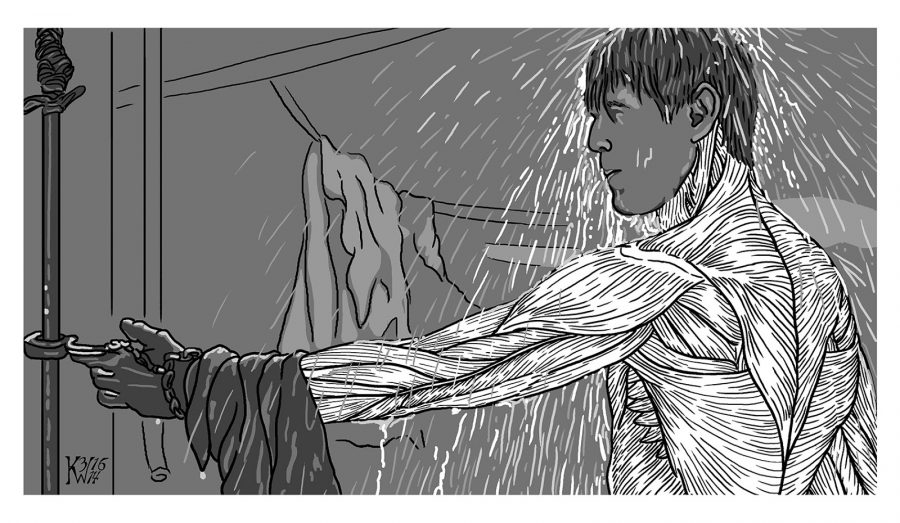

You’ll find a number of entries featuring the work of Japanese and Russian animators, including Thermae Romae, part of the juggernaut that’s sprung from Mari Yamazaki’s popular graphic novel series and Icarus and the Wise Men from the legendary Fyodor Khitruk, whose retelling of the myth sent a message about freedom from the Soviet Union, circa 1976.

Begin your decade-by-decade explorations of Chiara Sulprizio’s animated antiquities here or suggest that a missing favorite be added to the collection. (We vote for this one!)

Related Content:

Watch Art on Ancient Greek Vases Come to Life with 21st Century Animation

18 Classic Myths Explained with Animation: Pandora’s Box, Sisyphus & More

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in New York City for the next installment of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain, this April. Follow her @AyunHalliday.