Meditation and art have an ancient, intertwined history in China, where the beginnings of Chan Buddhism are inseparable from landscape painting. In Japan, Zen art has constituted “a practice in appreciating simplicity,” of disappearing into the creative act, cultivating degrees of egolessness that allow an artist’s movements to become spontaneous and unhampered by second guesses. The “first Japanese artists to work in [ink],” notes the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “were Zen monks who painted in a quick and evocative manner.” They passed their techniques, and their wisdom, on to their students.

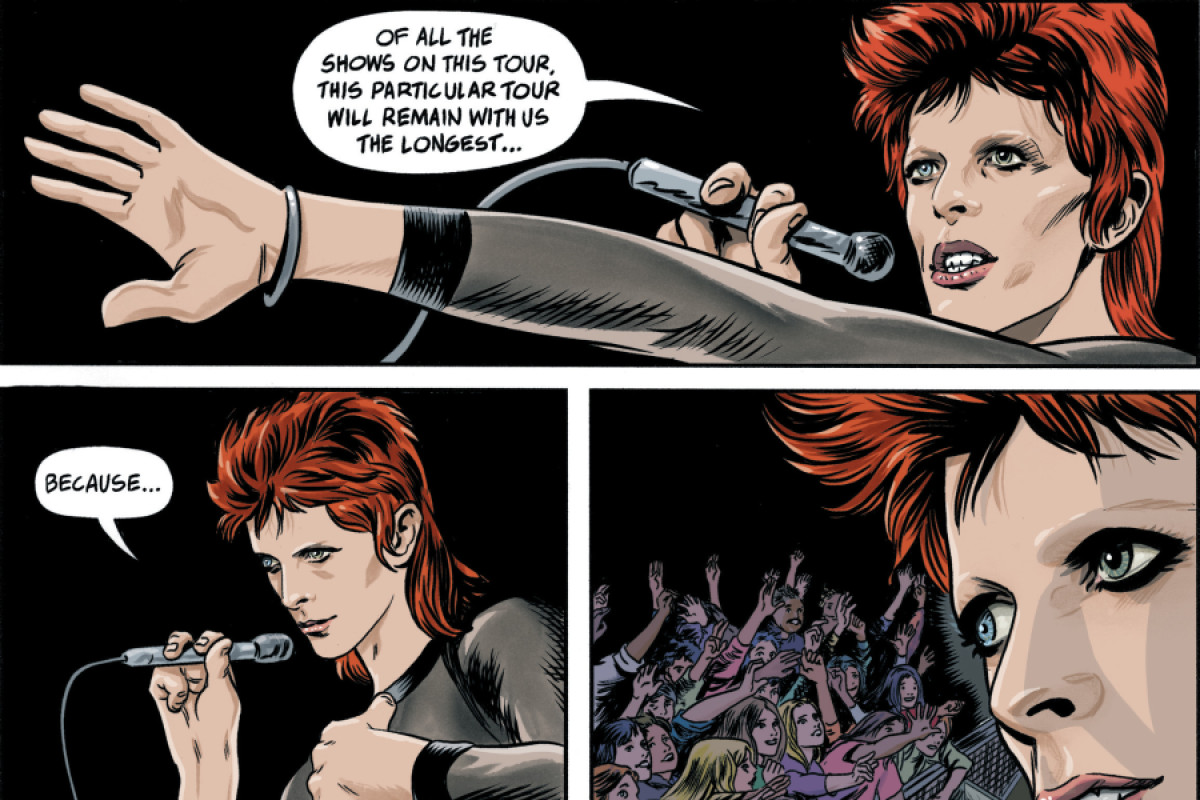

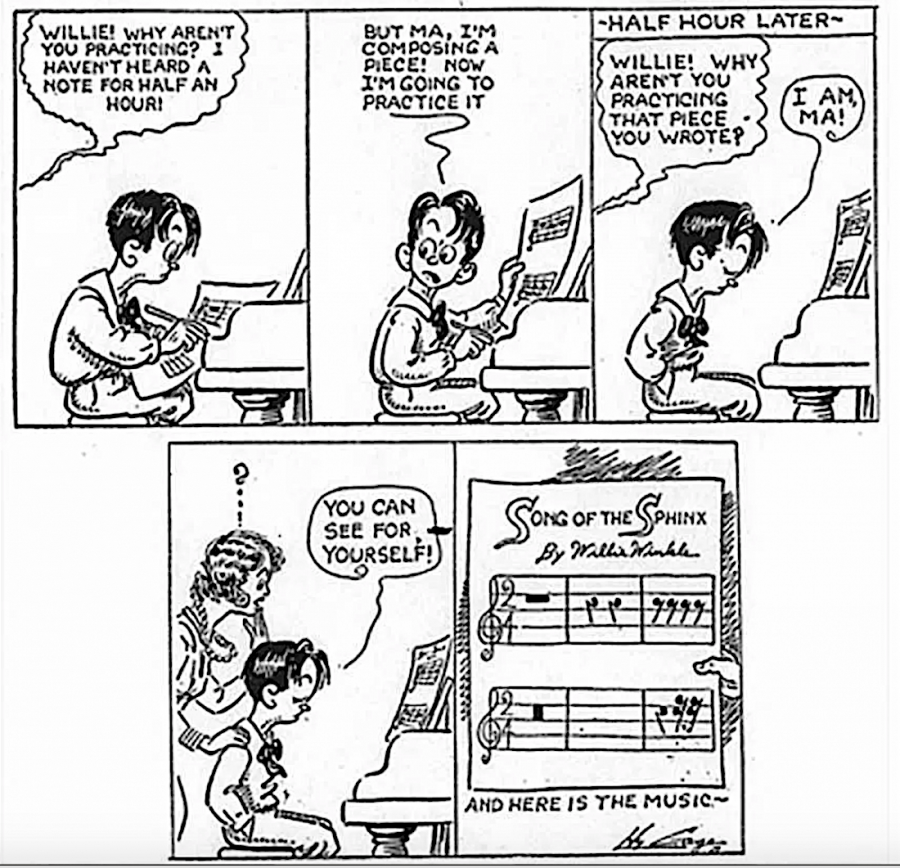

Perhaps the closest analogue to this tradition in the west is comic art. Artist Ted Gula has worked with comics legends Frank Frazetta and Moebius and drawn for Disney, Marvel, and DC. As a child, he watched Jack Kirby work. “He wouldn’t speak,” says Gula. “He’d be in a trance…. The pencil would hit the paper and it wouldn’t stop until the page was complete, like it poured out.” How is that possible? Gula asked himself, astonished. Kirby had disappeared into the work. There were no preliminary sketches or rough indicators. He would draw an entire book like that, Gula says in the video above from Proko.

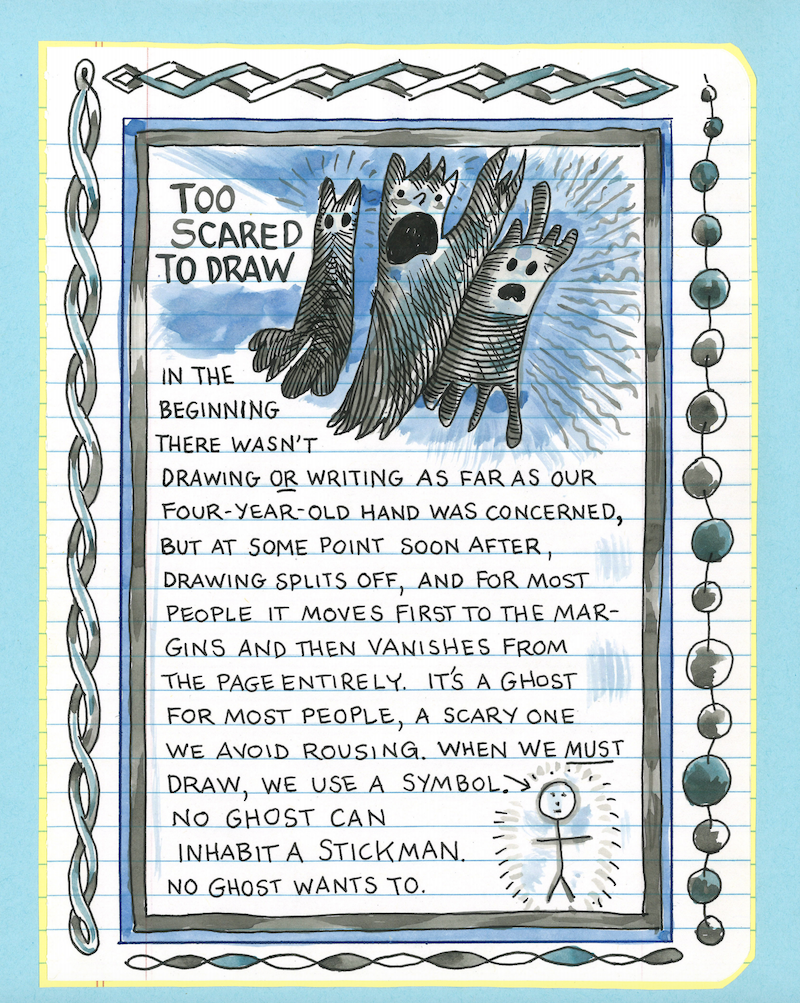

Say what you will about the content of Kirby’s work—superhero comics aren’t to everyone’s liking. But no distaste for the nature of his storytelling diminishes Kirby’s attainment of a purely extemporaneous method he seems never to have explained to Gula in words. Later, however, while working with Moebius, Gula says, he learned the technique of “automatic drawing.” Demonstrating it for us above, Gula describes a way of drawing that shares much in common with other meditative visual art traditions.

“It’s all doing very organic shapes,” he says, showing us how to “draw your mind’s eye. This takes your mind, and your mind’s eye, to a place that normally is unexplored, and it can’t help but enhance your whole view of your ability.” The ego must step aside, executive functioning isn’t needed here. “I have no idea,” Gula says, “it’s all just happening on its own.” Moebius explained it as “just letting my mind relax” and Gula has observed similar practices among all the artists he’s worked with.

Gula describes automatic drawing as a natural process for the artist’s mind and hands. The interviewer, artist and teacher Sam Prokopenko, also mentions Korean artist Kim Jung Gi in their interview, who does “amazingly accurate drawings from his memory without any construction lines,” as Prokopenko says above, in a video from his “12 Days of Proko” series, which interviews well-known artists about their techniques. What’s Kim Jung Gi’s secret? Is he possessed of a superhuman, photographic memory? No, he tells Prokopenko.

The secret to becoming fully immersed in the work—one that surely goes for so many pursuits, both creative and athletic—is just to do it: over and over and over and over and over again. (To many people’s disappointment, this also seems to be the secret of meditation.) In Kim Jung Gi’s case, “of course, some part of it is a talent he was born with, but we can’t overlook how much that talent was developed.” We need no expert talent, either innate or developed, to get started. Automatic drawing seems to require a beginner’s mind.

Related Content:

Moebius Gives 18 Wisdom-Filled Tips to Aspiring Artists

Watch Moebius and Miyazaki, Two of the Most Imaginative Artists, in Conversation (2004)

Moebius’ Storyboards & Concept Art for Jodorowsky’s Dune

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness