Maus, cartoonist Art Spiegelman’s groundbreaking, Pulitzer Prize-winning account of his complicated relationship with his Holocaust survivor father, is a story that lingers.

Spiegelman famously chose to depict the Jews as mice and the Nazis as cats. Non-Jewish civilians of his father’s native Poland were rendered as pigs. He flirted with the idea of depicting his French-born wife, the New Yorker’s art editor, Françoise Mouly, as a frog or a poodle, until she convinced him that her conversion to Judaism merited mousehood, too.

The characters’ anthropomorphism is not the only visual innovation, as the Nerdwriter, Evan Puschak, points out above.

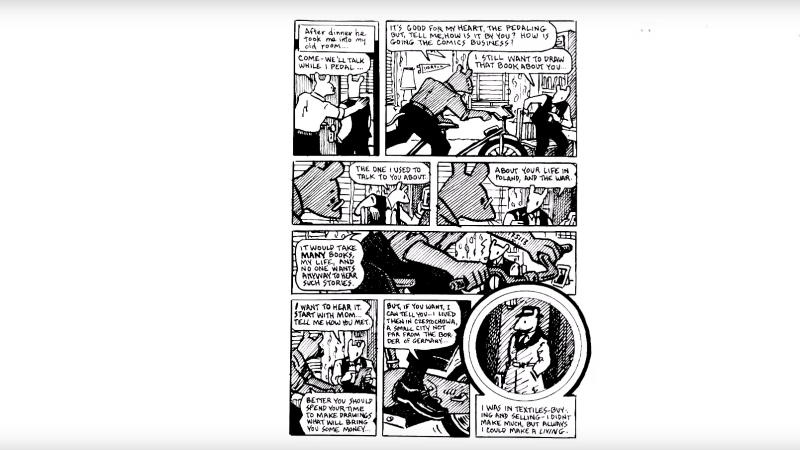

Drawing on interviews in MetaMaus: A Look Inside a Modern Classic, taped conversations with Neil Gaiman, and the University of Washington’s Marcia Alvar, and other sources, the Nerdwriter pans an eight-panel page from the first chapter for maximum meaning.

On first glance, nothing much appears to be happening on that page—hoping to convince his elderly father to submit to interviews for the book that would eventually become Maus, Spiegelman trails him to his childhood bedroom, which the older man has equipped with an exercise bike that he pedals in dress shoes and black socks.

But, as Spiegelman himself once pointed out:

Those panels are each units of time. You see them simultaneously, so you have various moments in time simultaneously made present.

Readers must force themselves to proceed slowly in order to fully appreciate the coexistence of all those moments.

Left to our own devices, we might pick up on the senior Spiegelman’s concentration camp tattoo, or the introduction of Art’s late mother via the framed photo he shows himself picking up.

But Puschak takes us on an even deeper dive, noting the significance of Art’s placement in the long mid-page panel. Watch out for the 4:30 mark, another visual stunner is teased out in a manner reminiscent of the revelation of a message written in invisible ink.

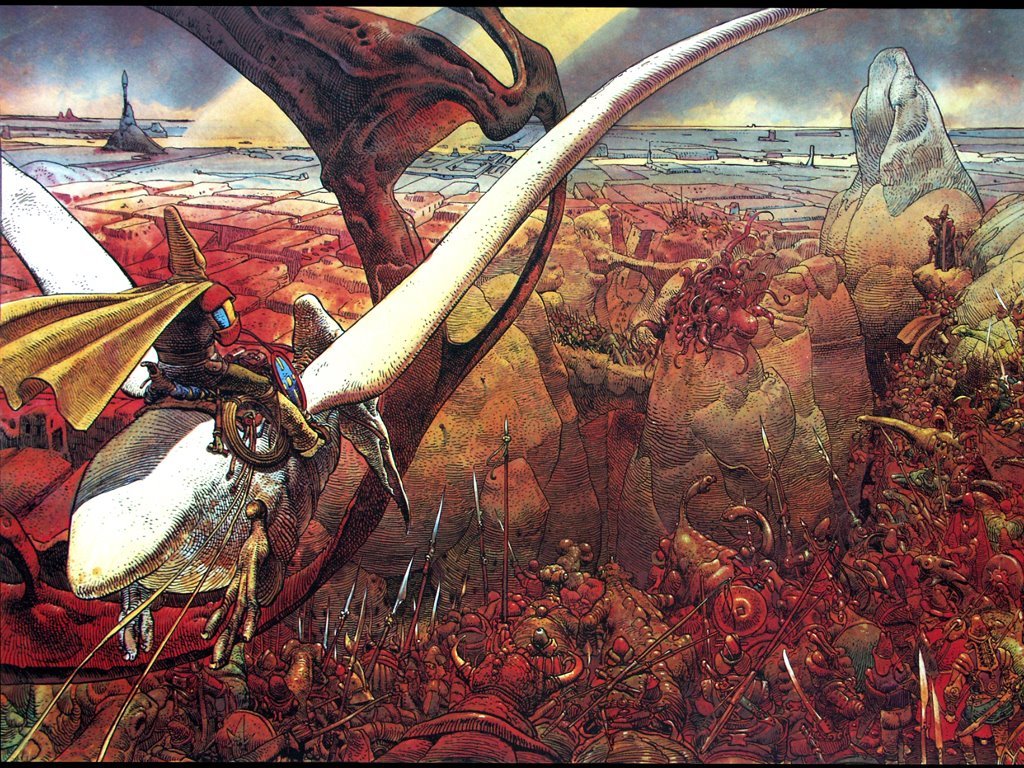

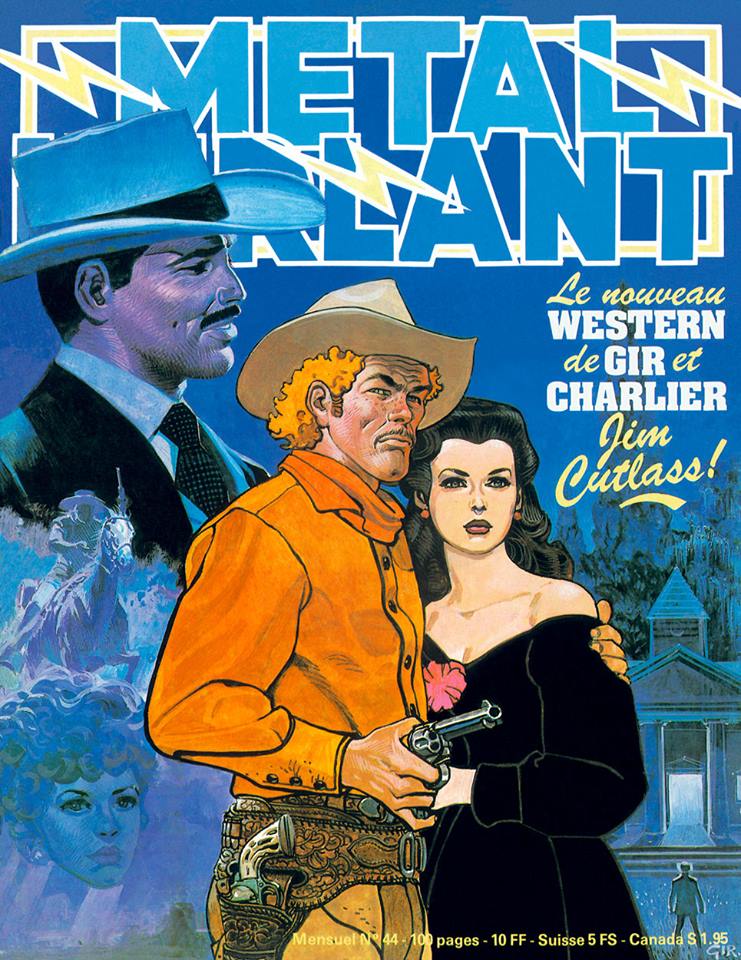

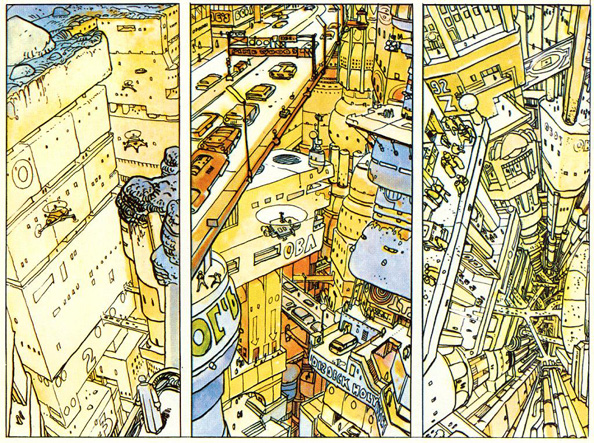

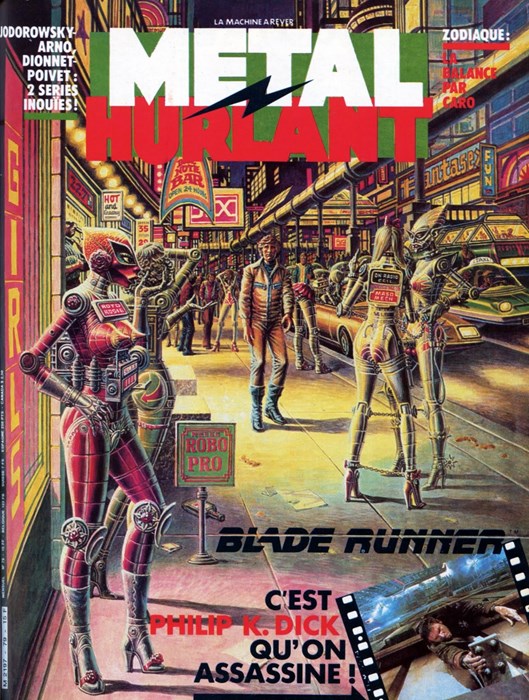

So Maus conferred commercial success upon its creator, while hanging onto some of the bold visual experiments from earlier in his career, when he and Mouly helped drive the underground comix scene—the past and present entwined yet again.

And this is just one page. Should you venture forth in search of further visual cues later in the text, please use the comments section to share your discoveries.

Related Content:

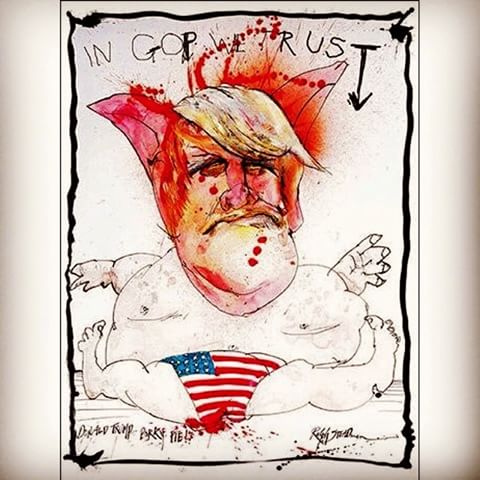

23 Cartoonists Unite to Demand Action to Reduce Gun Violence: Watch the Result

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.