Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury is hardly the cultural touchstone it once was, but then again, neither are comic strips in general, and political strips in particular. No amount of urbane witticism and sequential narrative humor can compete with the crazed jumble of arcane memes in the 21st century. Hunter S. Thompson may have written about the late-20th century political scene as a hallucinatory nightmare, but perhaps even he would be surprised at how close reality has come to his hyperbole.

In its heyday, Trudeau’s topical, liberal-leaning satire of politicians, political journalists, clueless hippies, and cynical corporate and academic elites hit the target more often than it missed. For many fans, one of Trudeau’s most beloved characters, Uncle Duke—a caricature of Thompson introduced in 1974—was a perfect bullseye. Writer Walter Isaacson paid tongue-in-cheek tribute to the character as his “hero” on the strip’s 40th anniversary. Duke even made an animated appearance on Larry King Live in 2000 (below), announcing his candidacy for president after serving as Governor of American Samoa and Ambassador to China.

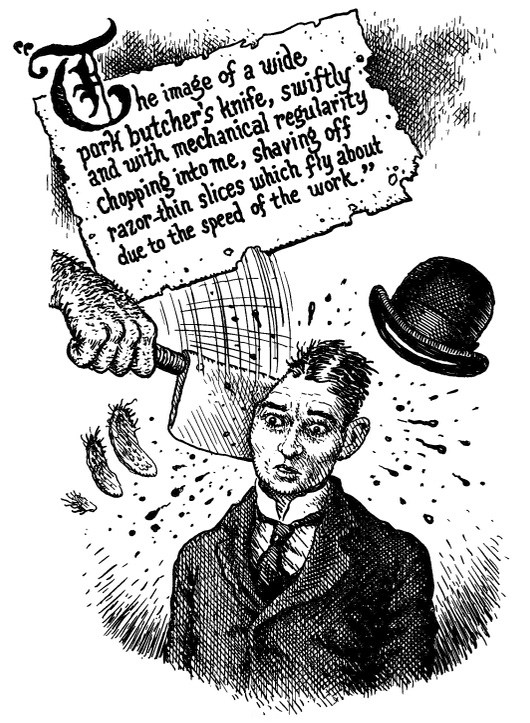

It would be a tremendous understatement to say that Thompson himself was not flattered by the portrayal. The amoral Duke—a “self-obsessed, utterly unscrupulous epitome of evil who has sent a chill down readers’ spines,” writes The Guardian’s Ed Pilkington, sent Thompson into a paroxysm of rage. The gonzo writer saw the character “as a form of copyright infringement.” He “sent an envelope of used toilet paper to Trudeau and once memorably said: ‘If I ever catch that little bastard, I’ll tear his lungs out.’” The threats got even more specific and gruesome.

“Hunter despised Trudeau,” writes Thompson biographer William McKeen in his book Outlaw Journalist. “’He’s going to be surprised someday,’ Hunter said. ‘I’m going to set him on fire first, then crush every one of his ribs, one by one, starting from the bottom.’” He had been turned into a joke. Jan Wenner, “when he couldn’t get Hunter to write for him… put him on the cover of Rolling Stone anyway, as Uncle Duke in a Trudeau-drawn cover.” Thompson pondered a $20 million libel suit. “All over America,” he ranted, “kids grow up wanting to be firemen and cops, presidents and lawyers, but nobody wants to grow up to be a cartoon character.”

The mockery began immediately after Uncle Duke first appeared in the strip in 1974. In a High Times interview, Thompson describes the day he first learned of the character:

It was a hot, nearly blazing day in Washington, and I was coming down the steps of the Supreme Court looking for somebody, Carl Wagner or somebody like that. I’d been inside the press section, and then all of a sudden I saw a crowd of people and I heard them saying, “Uncle Duke,” I heard the words Duke, Uncle; it didn’t seem to make any sense. I looked around, and I recognized people who were total strangers pointing at me and laughing. I had no idea what the fuck they were talking about. I had gotten out of the habit of reading funnies when I started reading the Times. I had no idea what this outburst meant…It was a weird experience, and as it happened I was sort of by myself up there on the stairs, and I thought: “What in the fuck madness is going on? Why am I being mocked by a gang of strangers and friends on the steps of the Supreme Court? Then I must have asked someone, and they told me that Uncle Duke had appeared in the Post that morning.

While Trudeau seems to have taken the physical threats seriously, he didn’t back down from his relentless satirical takedowns of Thompson’s violent tendencies, paranoia, and comically exaggerated substance abuse. As Dangerous Minds describes, in 1992, Trudeau published a book called Action Figure!: The Life and Times of Doonesbury’s Uncle Duke “that chronicled the misadventures of Uncle Duke.” It also “came with a five-inch action figure of the dear Uncle Duke along with a martini glass, an Uzi, cigarette holder, a bottle of booze, and a chainsaw.”

See the Uncle Duke action figure at the top—one of a half-dozen images Dangerous Minds pulled from eBay (his t‑shirt reads “Death Before Unconsciousness.”) As much as Thompson despised Uncle Duke, and Trudeau for creating him, he himself helped feed the caricature—with his alter ego Raoul Duke and his chronicles of his own bizarre behavior. Trudeau’s admiration, of a sort, for Thompson’s excesses was a continuing driver of the writer’s fame, for good or ill. “Uncle Duke was who fans craved,” writes Sharon Eberson at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, “and Thompson often felt obliged” to live up to his cartoon image.

Related Content:

Read 11 Free Articles by Hunter S. Thompson That Span His Gonzo Journalist Career (1965–2005)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness