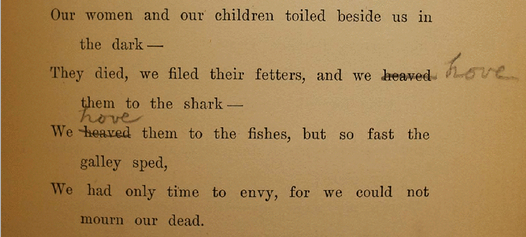

Hemingway once said that “all modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn.” Twain, however, was not only a master of subtlety and humor in fiction, but also a piercingly funny and sometimes scathing essayist whose pen ranged from politics to literary criticism. Despite publishing many biting essays, many of Twain’s best barbs never reached their targets. Instead they remained within the marginalia of his books. In a series of documents made public by the New York Times, Twain’s ire at sloppy writing makes itself known. Some comments, like this one regarding his friend, Rudyard Kipling, are fairly innocuous:

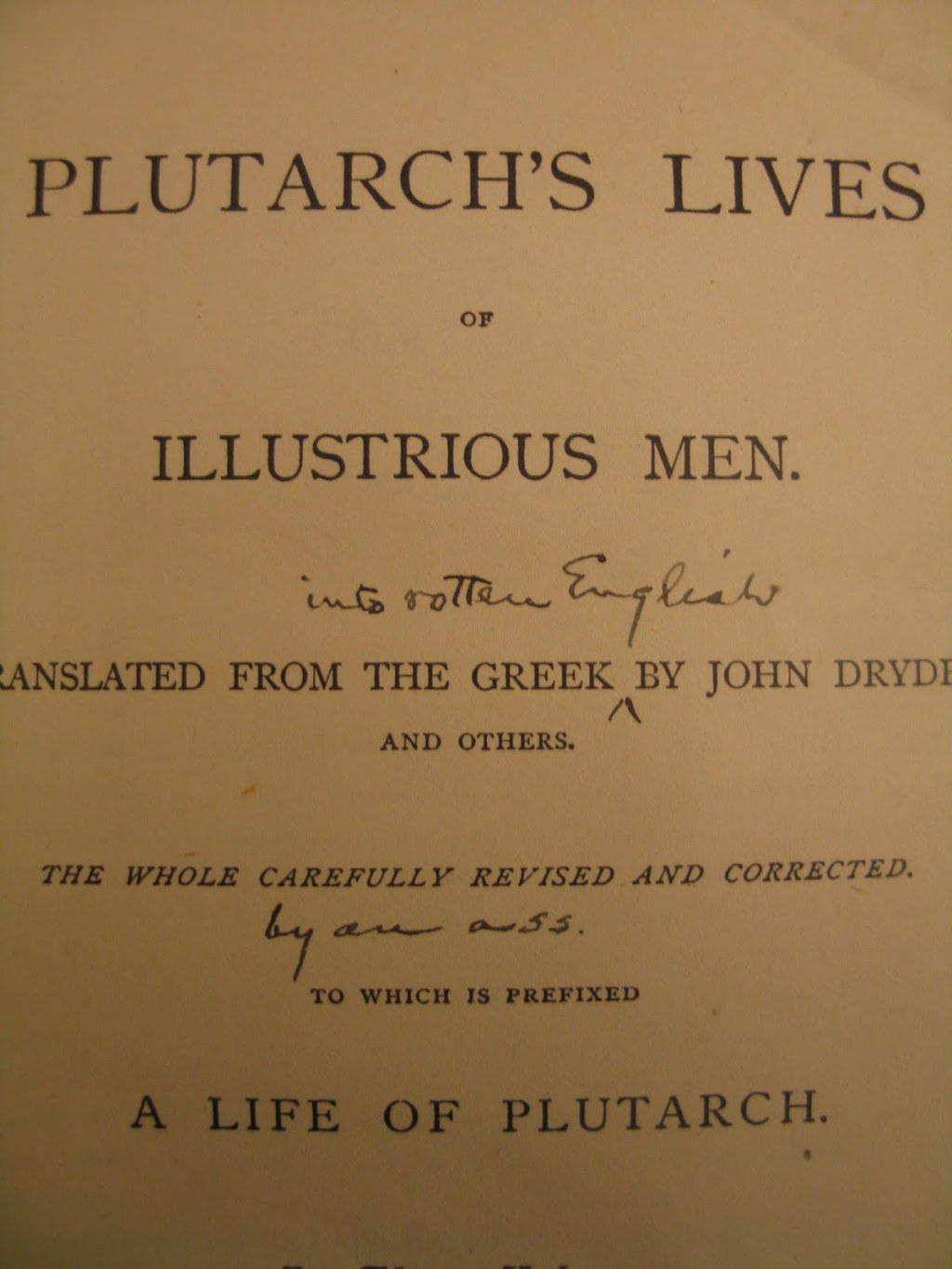

While Kipling got off lightly, John Dryden’s translation of Plutarch’s Lives seems to have hit a nerve, causing Twain to change the inscription to “translated from the Greek into rotten English by John Dryden; the whole carefully revised and corrected by an ass.” (Up top)

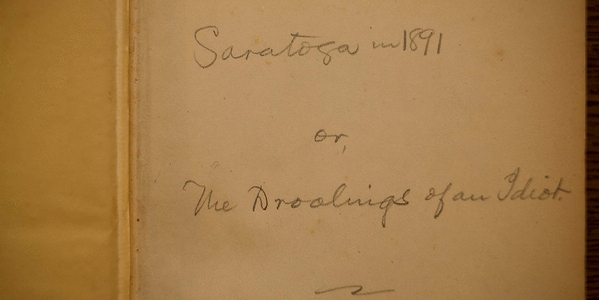

Notes in the margins of Landon D. Melville’s Saratoga in 1901 show that it fared no better. Twain, it appears, renamed the volume, dubbing it “Saratoga in 1891, or The Droolings of An Idiot.”

He also deemed some of the writings to be the “Wailings of an Idiot.”

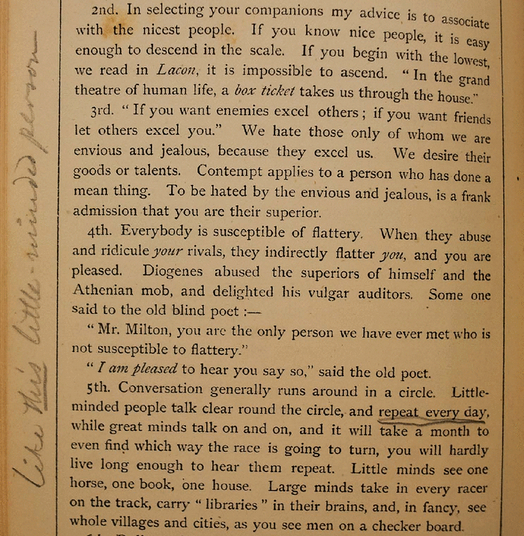

And, just so there wasn’t any ambiguity about what he thought, Twain labeled Melville a “little minded person.”

For more of Mark Twain’s jottings, head over to the New York Times’ document archive and The Mark Twain House & Museum.

Ilia Blinderman is a Montreal-based culture and science writer. Follow him at @iliablinderman.

Related Content:

Mark Twain Plays With Electricity in Nikola Tesla’s Lab (Photo, 1894)

Mark Twain Drafts the Ultimate Letter of Complaint (1905)

Mark Twain Captured on Film by Thomas Edison in 1909. It’s the Only Known Footage of the Author